Excited to once again present reading reviews from some of my favourite readers. Today’s installment, his third, is by Scott Walters. Scott launched a litblog, seraillon, in 2010, and expects to return to it one of these days. He largely follows Primo Levi’s model of “occasional and erratic reading, reading out of curiosity, impulse or vice, and not by profession.” He lives with his partner in San Francisco.

Barring a couple of possible late entries, here ends the 2023 edition of the EMJ Year in Reading series. Thanks to everyone who contributed–and all who read these engaging lists.

Year in Reading 2023: 50 Books, Fat and Thin

Like several others who have already posted about 2023, I had a less than stellar reading year, finishing a little over half the number of books I did in 2022. On the other hand, several doubled as barbells for building up my muscles. On the third hand, some were slim. And on the fourth hand, some were slim pickings; I can’t recall ever reading so many works I didn’t especially like. I’m not sure to what to attribute that deflating phenomenon, but I hardly seem to be alone.

Best Quasi-Rereading

Michael Moore’s effervescent new translation marked my fourth time reading Alessandro Manzoni’s The Betrothed (1827/1842). As Moore explained at a reading I attended, he deliberately aimed his translation at an American audience lamentably unfamiliar with this 19th century masterpiece. An ingenious framing story cocoons this long tale of Renzo and Lucia, the affianced young couple whose wedding plans are dashed by the machinations of a lascivious warlord, forcing the couple to separate and flee into spiraling trials that challenge them (and several other characters) into becoming larger than themselves. Starting a beloved book in a new translation requires adjustment, but I was won over by Moore’s energetic, nimble, vivid and playful version, almost certainly the place to start for any American reader approaching this grand work for the first time. [Ed. – This book looks at me reproachfully from the shelf…]

Other Italian Explorations

Giovanni Boccaccio: The Decameron

G. W. McWilliams’ translation of Boccaccio’s 1353 classic accompanied me throughout the year as the perfect post-pandemic [Ed. – sic] companion. You know the framing story: five young women during the Florentine plague of 1348 abandon the city and invite along five male friends to an empty villa in the hills where, each day for ten days, each tells a story to entertain the others. The depiction of the plague in the book’s opening is terrific, and the 100 stories, splendidly diverse, are by turns tender, ribald, moving, pointed. So is the warm banter between the young people as they introduce their stories and encourage one another’s efforts, the whole serving as a kind of instruction manual on storytelling (and as a model for confronting calamity). Boccaccio has become a favorite; I also spent time this year with his Famous Women and Genealogy of the Pagan Gods, the latter especially highlighting Boccaccio’s talent as a great writer of prefaces. [Ed. – Ok, you sold me on this!]

Dominic Starnone: The House on the Via Gemita (2023)

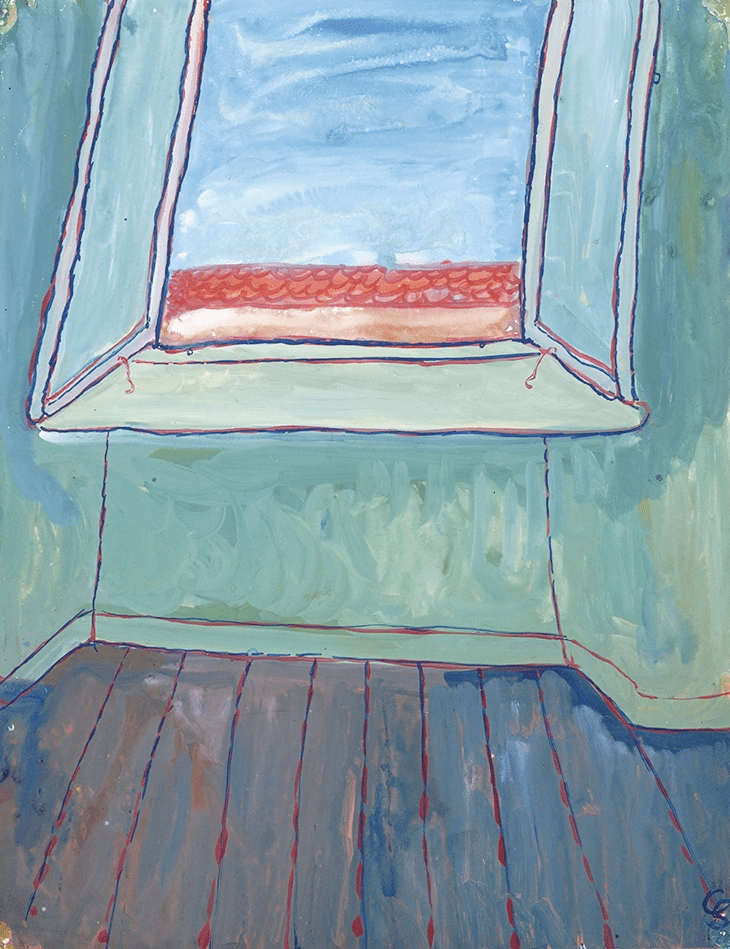

The two short Starnone Neapolitan novels I’d read had impressed me, so I was excited to discover a fat new 500-page work also set in Naples. Starnone’s narrator recounts the history of his father, digging so thoroughly into strained father/son relationship that I can’t imagine The House on the Via Gemita not taking its place as a classic of the genre. To my surprise, the book also turned out to be an excellent novel about painting, in that the son must address both his father’s abusive personality and role as a peripheral figure in mid-century Italian art, a career layered on top of a day job as a railroad worker and the family responsibilities he largely leaves to others. Starnone gives us a brief history of postwar Italian art while exploring the qualities that make paintings great or mediocre and making personal an issue of our time: disentangling (or not) an artist from their art. I also noted the geographical precision employed by Starnone as a quality common to several contemporary Neapolitan novels; one can use a map to follow the narrative’s peregrinations around the city.

Maria Attanasio: Concetta et ses femmes

Concetta et ses femmes, written in 2021 when Attanasio was 80, sets out as a documentary rescue mission to obtain the story of Concetta la Ferla, organizer in the late 1960s, in Caltagirone, Sicily, of the first women’s branch of the Italian Communist Party (then the third largest in the world). Concetta’s grassroots project develops out of frustration with the municipality’s diversion of water to its wealthiest citizens, but runs into predictable obstacles in the form of chauvinistic attitudes in the city administration, in the Party, and at home. The story would be interesting enough simply as historical artifact. But Attanasio’s structuring of her novel, the first part narrated by Maria herself from the perspective of 20 years after the effort to preserve Concetta’s tale, and the second the tale itself in Concetta’s words, plays with questions of authorship and feminist solidarity, and emphasizes the continual nature of the struggle to gain legitimacy, to advance the advances of the past, to never go back.

Other Italian/Italy-related works included an Italian/French collection of short stories (Nouvelles italiennes contemporaines), with Tomas Landolfi, Massimo Bontempelli and especially Elisabetta Rasy’s contributions as standouts. Indian-American-now-Italian writer Jhumpa Lahiri’s Roman Stories (2023) revisits Alberto Moravia’s 1959 Roman Tales (Racconti Romani in the original Italian for both books), exchanging Moravia’s focus on Roman men in recognizable neighborhoods for immigrants, ex-pats, and tourists vaguely on the city’s periphery. Renato Serra’s Examination of Conscience of a Man of Letters (1915) presents a searing treatise on the relationship of literature and war, written three months before Serra perished in battle in World War I (read in French; while the essay has never gone out of print in Italy, it has not been translated into English). I devoured Janet Abramowicz’s monograph, Giorgio Morandi: The Art of Silence (1964), a deep appreciation of the Bolognese artist into whose family Abramowicz was essentially adopted. Despite this proximity, Abramowicz treats her former teacher judiciously and even unsparingly when it comes to Morandi’s blemishes, in particular his tacit involvement with fascism. German writer Esther Kinsky’s Rombo (2022), a polyphonic novel exploring the impact of a series of earthquakes on remote villages in the north of Italy, grew on me during my reading, with its Polaroid-like narrative approach in which the lives of the villagers gradually become more vivid and saturated. Finally, in Etruscan Places (posthumous publication 1932), D. H. Lawrence and a companion identified as “B” voyage through central Italy, exploring sites of the ancient Etruscan “12 cities.” Lawrence’s incisive, infectiously enthusiastic observations about Etruscan art and life turned me into a fan of this fascinating people whose culture was absorbed/obliterated by the Roman Empire. The narrative doubles as a travelogue through Mussolini’s Italy and, adding yet another layer, Lawrence’s views lay out an entire philosophy that has me determined to revisit his fiction this year. [Ed. – I support this plan!]

Stalingrad

I came away from Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate convinced I’d encountered one of the essential literary documents of the 20th century’s experience of fascism. I did not know that the book was but a second volume in Grossman’s monumental effort to write the great World War II novel. The first, Stalingrad (1952), with still no definitive Russian edition, has only recently been translated into English by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler. As highly as I esteem Life and Fate, I believe Stalingrad may well be the superior novel [Ed. — !] in its immediacy and the sheer grandeur of its conception (but as the books were intended to form a whole, one need not set them against one another). Grossman, present at Stalingrad as a journalist, related some of his experiences in Life and Fate, but Stalingrad sets out to capture the whole story of the war’s most decisive battle, from August 23, 1942 to February 2, 1943. Grossman’s acute consciousness of his literary precursor, Leo Tolstoy, leads him to take his main character on two pilgrimages to Tolstoy’s house, Yasnya Polynka, and to muse on Tolstoy’s accomplishments:

Krymov looked at the wounded who had fallen by the wayside, at their grim, tormented faces, and wondered if these men would ever enter the pages of books. This was not a sight for those who wanted to clothe the war in fine robes. He remembered a night-time conversation with an elderly soldier whose face he had been unable to see. They had been lying in a gully, with only a greatcoat to cover them. The writers of future books had better avoid listening to conversations like that. It was all very well for Tolstoy – he wrote his great and splendid books decades after 1812, when the pain felt in every heart had faded and only what was wise and bright was remembered.

With Life and Fate, Stalingrad now gives us one of the great documents of World War II – and one of the greatest works of fiction about war ever written.

An Essential Holocaust Novel

The Talmudic concept of the Lamed-Vov, the 36 righteous people on whom the continuity of the world depends, fascinated me when first I read about it. Only when I started André Schwarz-Bart’s 1956 Prix Goncourt-winning novel, The Last of the Just, did I realize that the Lamed-Vov were central to the book. Schwartz-Bart takes the reader though a thousand years of Lamed-Vov succession to arrive at Germany in the 1930s, where the narrative pace slows dramatically. His restrained, almost clinically factual language provides devastating testament as much as fiction. Some of its scenes are completely indelible, and Ernie Levy, Schwarz-Bart’s protagonist for this last half of the book, struck me one of the most remarkable characters I’ve encountered in a lifetime of reading. [Ed. – It feels like a professional failing that I have not read this book!]

José Revueltas: The Hole

A tiny but shockingly powerful novella, taut and tight with not a word out of place. [Ed. – Funny, that’s how people usually describe me!] The Mexican writer and activist Revueltas’s 1969 book, based on the author’s own 12-year experience as a political prisoner, resembles a Piranesi prison drawing in narrative form, an intensely concentrated exploration of incarceration. Everything in the narrative is compressed – time, space, hope, even the reader’s attention and the size of the book itself. An absolute masterpiece of prison literature.

Good King Xavier, Reino de Redonda

Spanish novelist Javier Marías died at age 70 on September 11, 2022. I encountered his work four times this past year, first in his final novel Tomás Nevinson (2022) which appeared last May in Margaret Jull Costa’s translation. I had come to anticipate each new Marías translation as nearly an annual tradition, so knowing that this his last novel made reading it deeply bittersweet. Tomás Nevinson follows up 2018’s Berta Isla, but also resurrects characters from Marías’s Your Face Tomorrow trilogy, most notably Bertram Tupra. Where Your Face Tomorrow engaged Spain’s experience of Franco and of the civil war, Tomás Nevinson takes as its starting point the Basque separatist terrorist attacks of the 1990s. As Nevinson is enlisted by Tupra to come out of retirement to track down a woman involved in the most heinous of these attacks, Marías uses the narrative to explore questions about our responsibility for seeking justice, how we deal with repentance and redemption, what justice seekers owe to their own loved ones, whether there may be some informal statute of limitations on bringing the guilty to account and how long justice should be sought – time being among the most prominent fixtures in Marías’s fiction. We are fortunate to have this novel; Marías’s time having run out seems completely unjust.

When I picked up Tomás Nevinson at Point Reyes Books, the literary mecca cultivated by Molly Parent and Stephen Sparks, Sparks asked if I’d read the new book about Redonda. I must have stared at him blankly, as, having not yet read Marías’s Oxford novels, I knew nothing. Thanks to Michael Hingston’s marvelously strange Try Not to Be Strange (2023), I now know quite a lot, including the fact that Marías had been, up until his untimely death, King Xavier I, monarch of this tiny nation, which, despite having no inhabitants, does have territory, a flag, its own currency and postage stamps, and a plethora of dukes and princesses, counts and ambassadors, and multitudes of other titles held by what seems a who’s-who of 20th century writers. This was by far my most fun book of the year, uncovering a great story, offering up a charming tale of obsession (including Hingston’s own), and digging a dizzying warren of rabbit holes for one to scurry down, which led to my filling quite a bit of empty shelf space with related works. [Ed. – Well, this all seems quite insane!]

One of those works, of course, was All Souls (1992), the Marías Oxford novel in which the author first mentions Redonda. I expect to have more to say about this book after I’ve read its sequel, Dark Back of Time, on deck for 2024.

Another addition, Cuentos únicos (1996), came from Reino de Redonda, Marías’s own Spanish-language imprint.This collection of 22 translated English language short stories selected by Marías presented a way to practice my poor Spanish and get to know some writers I didn’t know. Nugent Barker? Oswell Blakeston? Percival Landon? [Ed. – Are these imaginary???] My Spanish proved inadequate to the task, but I understood enough to have made the effort – to be continued this year – worthwhile.

The Ascent of Rum Doodle Mont Analogue

My next-to-most-fun book of the year, René Daumal’s Mont Analogue (1952), tells the story of Père Solgon’s organization of an expedition aboard the ship “Impossible” to find the rumored tallest peak on earth, mysteriously as yet undiscovered due to its isolation (guesstimated to be in the vast South Pacific) as well as certain tricks of light that keep it invisible except at a certain hour and from a certain approach. With a crew including such luminaries as an American painter of alpine scenes, one Judith Pancake, the voyage is half tongue-in-cheek, half mystical imponderables (Daumal had been a follower of Gurdjieff), half Jules Verne. Yes, I know that’s three halves, but that suggests the shape and character of this delightful novel, one of the rare “unfinished” works that actually ends mid-sent-….

(Note: for French readers: a lovely new hardcover illustrated edition of Mont Analogue comes with an introduction by musician Patti Smith).

Weak in Comparison to Dreams

I got to know art historian/theorist James Elkins’s work some 25 years ago while researching text and image for a conference paper. So it came as quite a shock to discover a 600-page novel by Elkins, especially as I’d recalled his having announced in an Amazon book review his intention to stop adding to an accretion of texts. Presumably Elkins only meant Amazon reviews, because Weak in Comparison to Dreams (2023) is a welcome contribution to contemporary literature and among the most unusual novels I’ve read in a long time. In the book’s continuation of Elkins’s explorations of text/image interactions, I felt both that I was right back where I’d left off and in a whole new world. Incorporating scores of black and white images and increasingly nutty charts and graphs, the narrative follows its narrator, Samuel Emmer, a bacterial biologist for the city of Guelph, Ontario, on a series of visits to zoos around the world to evaluate mammalian behaviors and health protocols as Guelph plans its own zoo. [Ed. – The Guelph connection is… unexpected.] A dozen interchapters present Emmer’s dreams while on this mission, these too accompanied by images that suggest an intensifying fugue state. By turns sobering and hilarious, thematically touching on everything from animal welfare and incarceration to climate change and bureaucracy, from pseudo-science to contemporary experimental music, and playing in a space similar to that occupied by conceptual artist David Wilson’s Museum of Jurassic Technology, Elkins’s absorbing novel is… not at all what it seems. A 100-page final section entitled “Notes” delivers not so much “notes” as a surprising reframing of the first narrative, much in the way a caption might reframe an image. I can’t get the book out of my head, and shouldn’t, as Elkins has completed four other novels since 2008 that form a quintet of which Weak in Comparison to Dreams, though the first to be published, is volume three. I cannot wait to see what he does in the other four. [Ed. – How the hell do you find this stuff???]

The Queen of L.A. Noir

My familiarity with Dorothy Hughes’s In a Lonely Place (1947) had been limited to Nicholas Ray’s 1950 film starring Humphrey Bogart. Finally reading the novel left me incensed about the movie, a fairly egregious desecration of its source material. Fortunately, I felt no indignation in response to Hughes’s novel, which floored me as not just a masterpiece of Southern California noir, but perhaps the masterpiece of Southern California noir. I fell for it in the first pages, which captures the foggy, seeping chill of the California coast at night in a manner precise and true. She shies away from nothing in this penetrating psychological drama in which [Ed. – SPOILER INCOMING!] the narrator himself is the killer – presumably the quality that kept the studios from allowing Humphrey Bogart to be tarnished by such a role. Hughes covers the postwar L.A. noirscape exquisitely while managing to keep her narrator entirely human, a subtle literary feat that reads like one of Freud’s case studies. Raymond Chandler might be King of L.A. Noir, but if you asked me to pick a monarch, I’d go with Hughes on the basis of this novel alone.

Other mysteries included the marvelous Margaret Millar in Stranger in my Grave, a disappointing end to the Montalbano series in Andrea Camilleri’s Riccardino, and dismay as regards Mignon Eberhart, an author I’ve liked, whose Family Affair, in this year of too many books I did not like, marked the nadir.

Poetry

Aside from individual poems here and there, I read just three books of poetry. Reginald Dwayne Betts in Felon (2019) gives us a powerful collection of poems that go well beyond the experience of incarceration to address convict life beyond prison. I found Argentine poet Alexandra Piznarik’s Removing the Stone of Madness, Poems 1962-72 (Yvette Siegert, translator), relevatory. I did not know Piznarik, who, as the collection’s title suggests, fought a terrible battle with mental illness which she chronicled in short, sui generis poems as hard-edged and clean as crystals, powerful poem-objects one could almost hold in one’s hand. Finally, I loved Greg Hewitt’s intimate, resonant poems in Blindsight, structurally based on composer Olivier Messiaen’s prime-number system and which brought to mind Frank O’Hara’s personal poetic school of “Personism” (a mutual friend sent me Greg’s book).

Odds and Ends

The rest, an unorganized, mostly enjoyable mess, included Willa Cather, more Eve Babitz, Sándor Márai, Tatsuo Hori, Euripides, Chinua Achebe, Raphael Sánchez Ferlosio, more César Aira (an annual need), Daisy Hildyard and others. Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove (1985) gave me exercise, as with Stalingrad in one hand, I built up my other bicep by hefting McMurtry’s 850-page narrative in late-night installments at approximately the same pace as the Texas border to northern Montana cattle drive the story depicts. I found it terrific fun, amplified by my subsequent reading of the story of a poor Texas legislator who made the mistake of trying to ban Texas’s national novel. No one should want to be that guy. A bit further south I ate up Charles Portis’s Gringos (1991), set in the Yucatan where rumpled ex-pat Americans are involved in archeological dealings and mis-dealings. Are all of Portis’s novels his best novel? I think so. I think so. [Ed. – Well put!] Art historian Alexander Nemerov’s The Forest (2023), a collection of essays and corresponding plates, uses forests of the American frontier to cull idiosyncratic tales of 1830’s American art and culture, rescuing some fascinating figures from historical oblivion. I finally got around to reading Maggie Nelson, in Bluets (2009) and The Argonauts (2015) – respectively, musings on the color blue (with a towel snap at William Gass’s bare cheeks), and raw meditations on sex, gender and motherhood that I sent off to goddaughter pursuing gender studies. I’d been curious for some time about Michael McDowell six-volume Blackwater, and gorgeous and affordable new French paperback editions provided an opportunity to dive in. Blackwater 1: La Crue (1983) proved a Southern Gothic slow drip horror tale peeling away the veneer of Southern gentility. For the first time since high school, I revisited J. D. Salinger, in Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters (1955) and Seymour: An Introduction (1959). Salinger himself may not have aged well, but these two novels were far better than I expected them to be. I found Tove Jansson’s The True Deceiver (1982) to be a stunningly good novella about truth, trust and deceit, not necessarily in that order, set in a fishing village on the Finnish coast. There seems to have been nothing Jansson couldn’t do right. While somewhat confined in a house in the mountains, I found appropriate companionship in Count Xavier de Maistre’s A Journey Round My Room (1795), a book born of boredom, a curious meditation on escaping it, created when, following a duel, de Maistre was put under house arrest for some six weeks. Alleviating boredom, Roy Lewis’s The Evolution Man, or How I Ate My Father (1960), though clearly dated, was still pretty damned funny as comedies about pre-history go. Finally, a couple of books with which I struggled still held enough of interest for me to get through them. Justin Torres’s Blackouts (2023) relies heavily on photographs, drawings, redacted text, dialogue as film script, and other novelties that I found a bit overcooked (in a way I did not with the Elkins novel). But the story Torres unearths of a 1942 study of homosexuality, and of the lesbian couple who helped drive the project and were betrayed by it, is remarkable. I had a tougher time with Gerald Reve’s The Evenings (1947) acclaimed by some as the great 20th century Dutch novel. A disaffected young man lives with his numbed parents in 1946 Amsterdam and battles his claustrophobic life with dark, acrid humor. I admired Reve’s allowing the war to drip into the narrative bit by bit, the horrors of the recent past seeping into normal life. But I couldn’t wait for the book to end.

I’ll conclude with a dream. In a cluttered bookshop, I found a tattered but astounding volume amended with striking collages, vivid watercolor sketches, and dense margin notes. The (dream) author’s name seemed familiar, so upon waking I looked up James Gould Cozzens and plunged down a trail that led me to Dwight MacDonald’s 1958 review of Cozzens’ late novel, By Love Possessed. I did not read Cozzens. I’m not sure I will ever read Cozzens. But I’m grateful to odd dreams for having pointed me to MacDonald’s review, which takes to task a generation of critics who, with log-rolling fealty and conformity to one another’s uncritical opinions, lavished praise on the novel. Eviscerating, illuminating, even necessary, his review models close textual analysis with an eye towards criticism’s larger role, relevant today when writer-critics blurb one another’s books and award prizes to mediocre works. A pretty good way to end the reading year, and a better way to start off a new one which, I am happy to say, as far as books go, is off to a tremendous start. Thank you for reading. [Ed. –Thanks for writing, Scott! A delight as always.]