Regular readers will know that for the last several years I’ve solicited Year in Reading reflections from friends and trusted readers. As we’re well into February, I’ve scaled the project back considerably this time, but quality takes quantity every time… Today’s installment, his fifth, is by James Morrison, reader extraordinaire. James lives and works in Adelaide, on unceded Kaurna territory.

Working out which books to write about for these discussions is always fraught—there are easily another twenty great books I could have raved about, but neither you nor I are made of infinite time. I’ve tried to narrow things down to a few broad categories, but even then a few books would not be restrained by such, so they’re tacked on at the end.

In a couple of other people’s year-end reading round-ups on Bluesky, they talked not about what they’d read, but why they’d read it—what had prompted them to buy or pick up the books they ended up reading. It was strangely interesting, at least to a big horrible nerd like me, so I’m including that here for my own choices. Feel free to pass over it with glazed eyes. [Ed. – No way! I think people love that stuff. I know I do.]

RAMUZ

My most compelling new-to-me writer discovery of the year was Swiss novelist Charles Ferdinand Ramuz (1878–1947). The three of his books that I read all have the same basic premise—Something Horrible Happening in the High Alps—but go off in very different directions. Great Fear on the Mountain (translated by Bill Johnston) was what got me hooked first: a historical novel where a group of men set off to take the village’s flock up through a mountain pass to find feed, and then everything goes to hell. It has all the rhythms of an 1980s horror movie, but is beautifully written and was first published in 1926. Derborence [When the Devils Came Down] (translated by Laura Spinney) features an avalanche and its spooky survivor, while Into the Sun (translated by Olivia Baes and Emma Ramadan) is an impressionistic, atmospheric early climate change novel. As the Earth slowly falls into the sun, the snows melt, the mountain lakes boil, and society collapses into violence and despair.

Why: Nathaniel Rich’s splendid overview of Ramuz’s work in the NYRB.

BIG FAT EPICS

For some reason 2025 became a year in which I started, and sometimes finished, a number of big fat epics. [Ed. — Always big and fat, the epics.] Look at me, aren’t I tough?

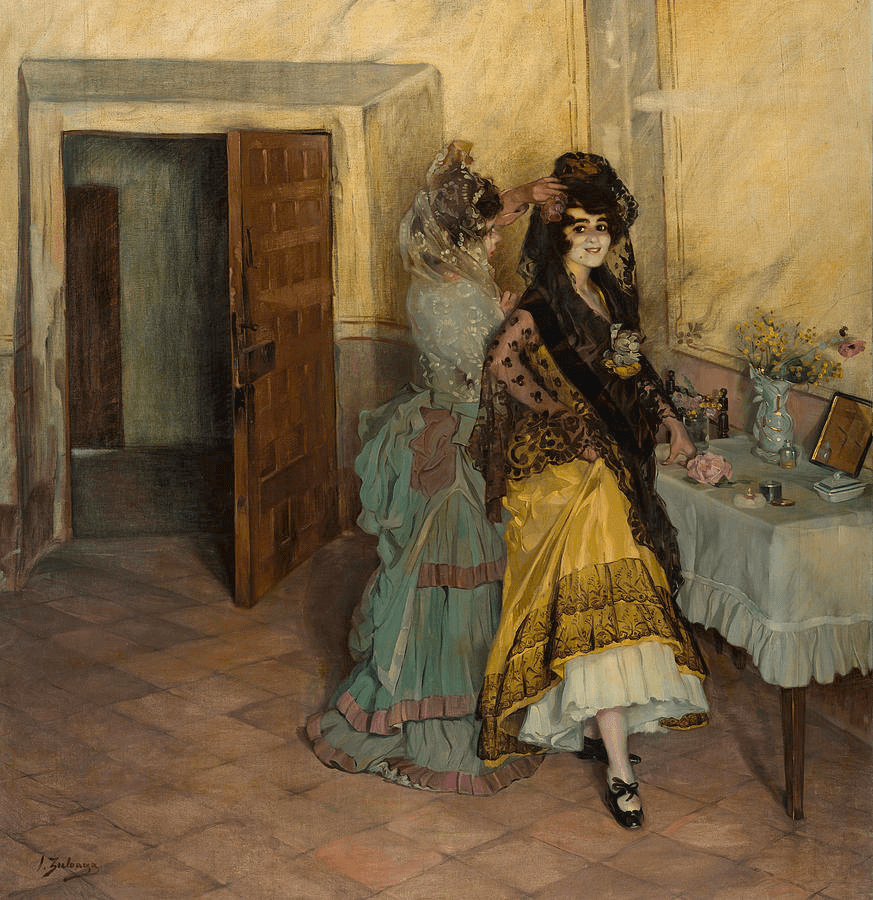

Miklós Bánffy, The Transylvanian Trilogy/The Writing on the Wall (translated by Katalin Banffy-Jelen and Patrick Thursfield): I had actually read this massive Hungarian modern classic before, some quarter-century ago, but remembered very little other than it was hugely enjoyable. If anything it was even better this time around, now that I am older and theoretically wiser. Aristocratic Hungarians in Transylvania scheme and gamble and party and fuck, fighting for their rights as a minority in the Habsburg Empire while simultaneously being unable (for the most part) to see how they are simultaneously repressing and neglecting the Transylvanians whose land they rule. And all the politicking and manoeuvring takes place as the Great War draws closer, ready to sweep their whole world away. It’s like a vastly more incident-packed counterpoint, set at the other end of the Empire, to one of my other favourite books, Musil’s The Man Without Qualities. [Ed. – James and I as always on the same wavelength…]

Why: Over recent years I’ve been going back to a number of books I remember as brilliant, to see if they actually are. For the most part, fortunately, they have been.

Solvej Balle, On the Calculation of Volume (translated by Barbara J. Haveland, Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell): Happy to say I fell for the hype and read the three books of this septology so far available in English. It’s a closely observed and beautifully written variation on the “Groundhog Day” premise of being stuck reliving the same day endlessly, but adding more and more wrinkles and complexities as the looping time passes. Fortunately this seems to be doing extremely well in English, so there’s every chance that, assuming Balle finishes the series, we’ll get to see all of it in translation. If she doesn’t, you’ll see me frothing blood in a tempest of rage.

Why: Though not original, the premise is fascinating, and I fell for the hype.

Dorothy Richardson, Pilgrimage: I read the first four books of this 13-volume modernist masterpiece, and while each book individually was excellent, the cumulative effect of this subtle, witty and awkward fictionalised autobiography is even more impressive. I hope to read the rest of this massive thing in 2026.

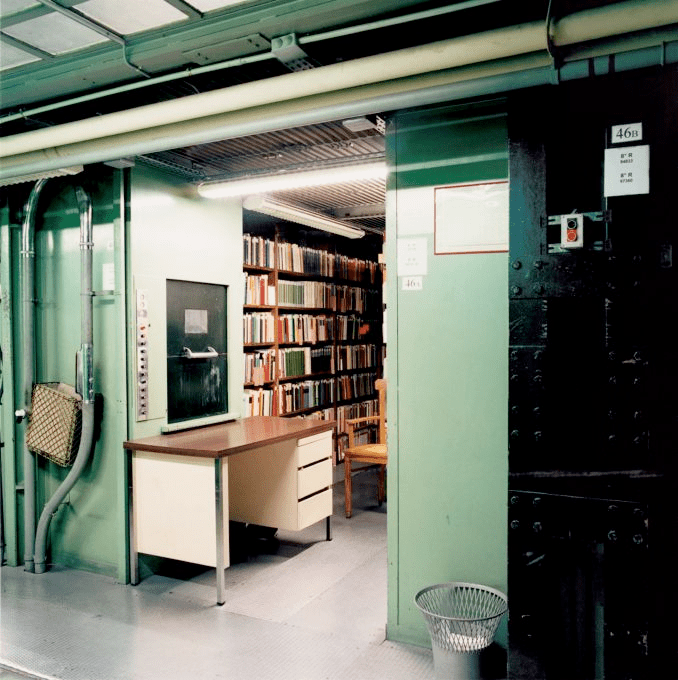

Why: I’ve wanted to read this for decades, but Virago’s treatment of their Modern Classics heritage being what it is, it’s never been possible to get all four volumes of the collected edition. Fortunately, Brad Bigelow of Neglected Books published his own edition, and I finally got my disgusting paws on it.

Len Deighton, the Bernard Sampson series: In terms of pure, sardonic, exciting and bleak reading pleasure, it’s hard to go past this trilogy of trilogies about the much put-upon spy Sampson, his extremely complicated wife, and his infuriating superiors. I still have the last three books to go, so that’s another treat in store for 2026, assuming any of us live. [Ed. – James. A little less truth-telling, please. As to these books, I’ve only read the first three so far, but they are terrific.]

Why: I’d only ever read a couple of Deightons in the past, and they were excellent, so why it took me until now to realise just how good he is and just how pleasingly extensive his back catalogue is must stand as a testament to my general dimwittedness.

C. J. Cherryh, The Morgaine Saga: Extremely futuristic science-fiction masquerading as swords-and-magic fantasy, this trilogy of novels (there’s a fourth, published much later, which I have yet to get) is so richly imagined, and so cleverly paced and written, that it makes you despair about how crap most of its genre competition remains. Outcast prince, magical witch queen, brutal politics, war, extremely difficult moral choices, aliens; the whole shebang.

Why: Every now and then I get the urge to read some fantasy to recapture the kick it used to carry when I was a teenager. Sadly I am no longer a teenager with a teenager’s standards, and almost every time I give up on whatever overpraised nonsense I’ve been tricked into reading. This was one of the rare exceptions.

Homer, The Odyssey (translated by Emily Wilson): Only a single (big fat) book this time, but one I haven’t read in 20 years, and the newish Wilson translation was calling to me. And it’s great! I’d forgotten just how oddly structured the book is (the famously interminable journey home of the hero taking up a relatively small part of the story), and how mental some of the developments. And apparently, she’s going to retranslate it and publish a whole new version? [Ed. – Seriously???] Seems like sheer madness to me, but I guess that’s what working in academia does to someone. [Ed. — Laughs bitterly]

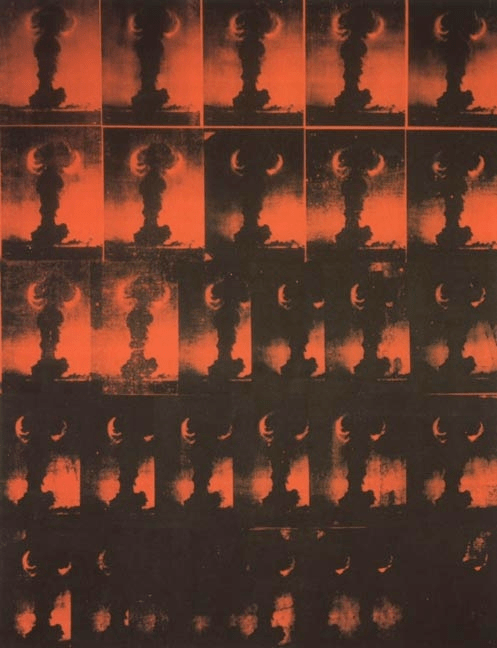

KILL ALL NAZIS

Why: All the worst people seemed to be enraged by Wilson’s translation, and her gender, so I could not resist. [Ed. – Yeah, those guys suck.]

All Nazis must fuck off and die. Here are some books about what they were like, and how they were dealt with, first time round…

Marie Chaix, The Laurels of Lake Constance (translated by Harry Mathews): Astonishingly good in English, and the French original is apparently even better? How can this be? An autobiographical novel from the point of view of the daughter of an enthusiastic French Nazi and traitor before and during WW2. Unsensationalised, elliptical, and marvellous.

Why: It looked both pretty and interesting in the bookshop, and that’s all I needed to see.

Uwe Wittstock, Marseille 1940: The Flight of Literature (translated by Daniel Bowles): A day-by-day, sometimes hour-by-hour, account of the lives, desperation, plots and betrayals of the huge array of German and Austrian writers and artists who fled the Nazis to France, only to have France fall soon afterwards. Lucid and utterly fascinating.

Why: Wittstock’s previous book, February 1933: The Winter of Literature, did the same thing for the month the Nazis came to power, so there was no way I was not going to read this follow-up when it appeared.

Grete Weil, Last Trolley from Beethovenstraat (translated by John Barrett): An obsession with a lost friend taken by the Gestapo in Amsterdam spills into the post-war life of a man now living in Germany. He marries the man’s sister in a confused, guilt-fuelled attempt to try to bring him back to life. Complications ensue, as you might expect. Rich and compact, and highly recommended. [Ed. – More on Weil here…]

Why: If I see a book in the Verba Mundi series, I buy it. It’s an eclectic but extremely well-selected library of translated literature from all over the world.

Lorenza Mazzetti, The Sky is Falling (translated by Livia Franchini): Another fictionalised memoir, about a pair of sisters sent to stay with Jewish relatives in Tuscany—relatives then slaughtered by the Germans in 1944 (Mazzetti always believed they were killed for the Nazi-perceived crime of being related to Albert Einstein). The beautifully observed child’s viewpoint contrasts with the horrors of the confused world she inhabits, and the book’s brevity gives it the intense kick of all the best novellas. [Ed. – Fascinating! Ordering now…]

Why: This was the first book released by a new feminist publisher, Another Gaze Editions, whose output focuses on the work of women filmmakers like Mazzetti. It’s a hell of a promising way to kick things off.

HOPELESS FUTURES

Jane Rawson, Human/Nature: Rawson is a fine and unusual Australian novelist whose first book was a manual on climate change survival. In this non-fiction return she takes a simultaneously despairing and bleakly funny look at the horrible state of things, what it all means, and where it’s all leading. None of it’s good, but at least it’s wonderfully written. We still have good prose, if nothing else.

Why: I love the author and would buy anything she wrote.

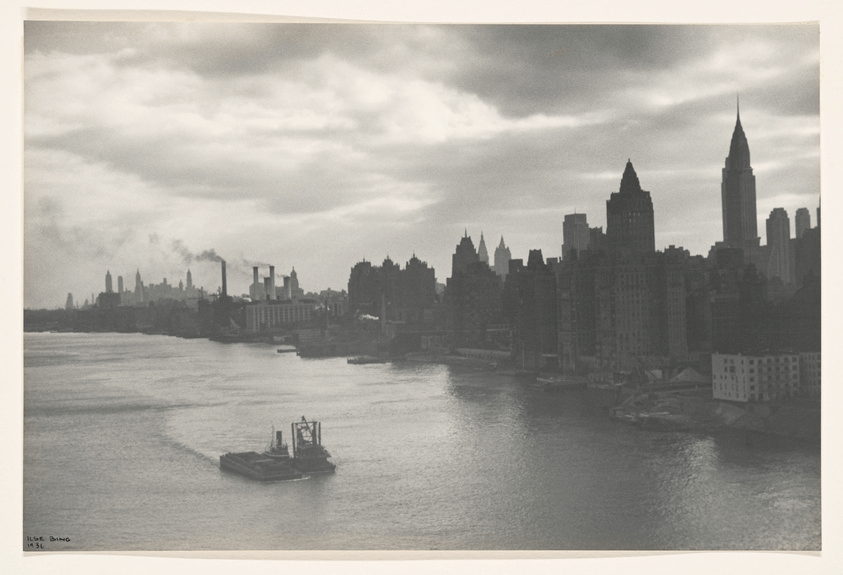

Jack Womack, Random Acts of Senseless Violence: Somehow I missed this in 1993 when it first came out, more fool me. In the convincing form of a young girl’s diary over several months in (then) near-future New York as everything falls apart under gun-wielding late-stage capitalism, it’s amazing how much this gets right, yet it’s also a strangely analogue vision of the future. It also posits a series of successful US presidential assassinations, and sadly the real world seems unable to provide any of those.

Why: It’s now an established science-fiction classic and I needed to read it.

Bradley Somer, Extinction: A ranger tries to protect the last living bear in North America from poachers. Gripping and downbeat and all-too believable. [Ed. – Why are these all so depressing???? *re-reads section heading* Oh.]

Why: Impulse remainder purchase that panned out extremely well.

PARENTS AND OUR MYRIAD FAILURES

Krystelle Bamford, Idle Grounds: Astonishingly good debut in the collective first person, told by a group of unmonitored children at a family party as they get bored, muck around, encounter something wrong in the garden, and go searching for one of their number who vanishes. Spooky, funny, original stuff. I couldn’t recommend this book more highly, to be honest.

Why: The cover of the UK edition, with a picture of roped-together monochrome children lost in a field of fluorescent green, was enough to convince me. [Ed. – I wish more people talked about how book covers influence their buying.]

Violette Leduc, Asphyxia (translated by Derek Coltman): A well-named book if ever there was one, this dense little novella details the suffocated life of a young girl with an unloving mother in rural pre-War France. But, flinty matriarchs aside, it’s also a richly drawn world of natural wonders and discoveries.

Why: I only discovered Leduc in the last few years, and she was such an extraordinary writer. This was published as part of a very small collection of French classics by female writers by Gallic Books.

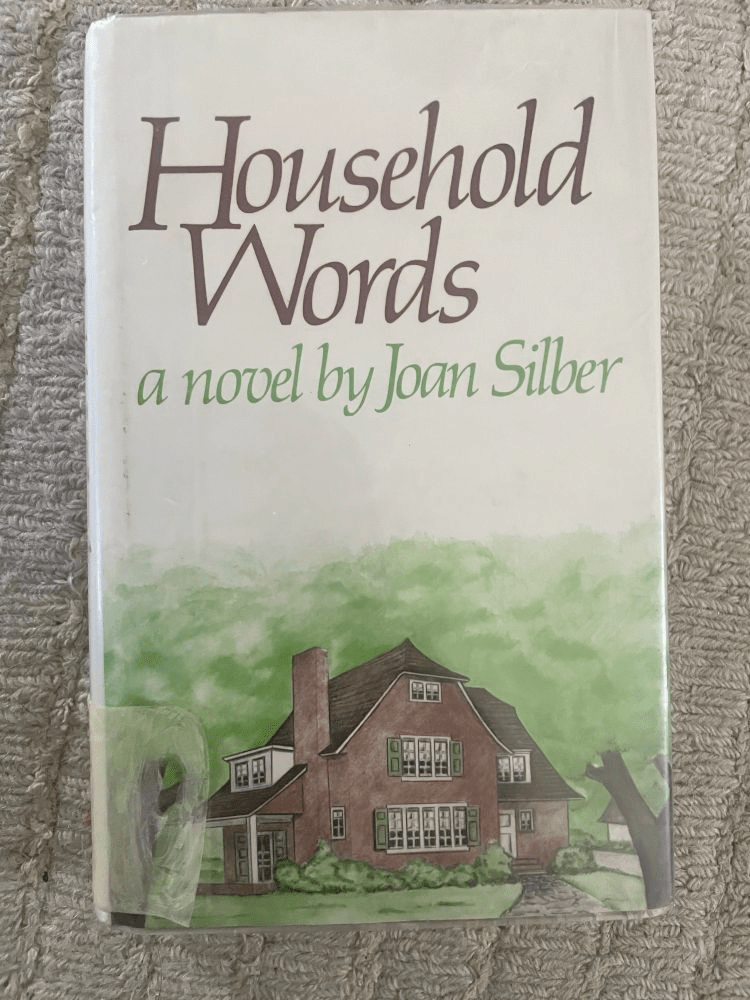

Adrian Nathan West, My Father’s Diet: A wonderful book that takes some well-known signifiers of modern American fiction (hollowed-out suburbs, emptying malls, masculinity in crisis, etc etc) and does new and strange things with them. A depressed son learns his father has, out of nowhere, become an obsessive bodybuilder, determined to win the Body You Choose competition. The characters are never caricatures, and it’s extremely funny despite the quiet desperation of it all.

Why: One of the many excellent books put out by And Other Stories, and this is from before they went for their current ugly typographic covers. [Ed. – James! I love those covers!]

GRAPHIC NOVELS

Lee Lai, Stone Fruit and Cannon: Australian (but now based in Canada) artist Lai’s two graphic novels are both minor masterpieces, and genuinely full novels in complexity and subtlety. Sad and perceptive dissections of failing relationships, parenthood, faltering elders, exploitative friendship, and being part of the Chinese diaspora.

Why: This review in Meanjin, an 85-year-old Australian literary magazine currently being put to death by the witless timid bureaucrats who cower in terror of angry letters from the Zionist lobby and who are ruining pretty much all the arts in Australia at the moment.

Emily Carroll, A Guest in the House: A seriously Gothic tale of madness, downtrodden femininity and hapless stepmotherhood, drawn with Carroll’s usual visual flair and attention to detail.

Why: I’ve raved about Carroll before, and love all her work. Somehow, to my annoyance, I didn’t even know this book, published in 2023, existed until I saw a copy a couple of months ago. My spies failed me. [Ed. – Maybe they were busy failing to assassinate US Presidents.]

UNCATEGORIS[ED/ABLE]

Mariette Navarro, Ultramarine (translated by Eve Hill-Agnus): Wonderfully unsettling novel about a woman captaining a cargo ship with a male crew. In the middle of the Atlantic they stop for everyone to have an illicit swim—and when everyone climbs back on board there’s one extra person.

Why: The Deep Vellum edition (already a recommendation) has a great cover with a vast cube of ocean on it, and I am only weak flesh.

Li Qingzhao, The Magpie at Night (translated by Wendy Chen): A beautiful collection of the complete surviving poetry by one of China’s greats, from the Twelfth Century. I mean, get a load of her perfect description of a lazy, drunken evening, from ‘As in a Dream’:

Remember that day

spent on the stream,

watching the sunset glaze

the pavilion.

So drunk, we could not find

our way back.

It was late when we had enough.

We turned the boat around

and were caught, accidentally, in the deep

tangle of lotus roots.

Rowing through, rowing through –

startling, from the banks,

herons.

Why: Having only read a couple of her poems in anthologies, it was a pleasure to find her complete works available in English.

J.M. Coetzee & Mariana Dimópulos, Speaking in Tongues: If you’re at all interested in translated literature, and in the process of translation itself, this is a very rewarding book. Two novelists and literary translators discuss what translation is, what it does, how it works, and a peculiar but intriguing project they undertook (and which was foiled by commercially minded publishers) to make the translated Spanish text of one of Coetzee’s novellas the “original” version of the book.

Why: If the topic is this interesting and the two writers involved this good, what sort of a fool would I be to not read it, I ask you?

[Ed. — A fool indeed. As is anyone who reads this and doesn’t head to their local bookstore or library ASAP on the hunt for some of these recs. Thanks, James!]