Earlier this semester, I presented for the third time at the annual Arkansas Holocaust Education Conference. In addition to giving the keynote talk (“Holocaust 101”), I also taught a session (basically, a class). The conference has an unusual format and remit. It is designed for high school students, their teachers, and interested community members. In a single busy day, participants hear two plenaries plus a presentation from a Holocaust survivor, and attend two breakout sessions from a selection of about six or seven.

I love being able to teach such a wide range of ages and experiences: a typical session will include as many retirees as 15-year-olds. The unusual format comes with its own challenges, of course: keeping the students from feeling intimidated by the adults; making sure the older participants really listen to the younger ones. By making participants work together to close read something, I seek to put everyone on the same footing and build a sense of community.

My session this year was called “Strangers in their Own Land: Jewish Self-Awareness in Holocaust Memoirs.” As I’d like eventually to turn it into a more formal piece of writing, I thought I’d transcribe my lesson plan here.

Ruth Kluger

The handout that we used for our exercise was headed by two quotations; together, they offer a condensed version of what I was hoping the participants would learn:

I had found out, for myself and by myself, how things stood between us and the Nazis and had paid for knowledge with the coin of pain.

—Ruth Kluger

To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.

—W. E. B. Du Bois

At first glance, Kluger—the Viennese-born survivor of Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, Christianstadt, and a death march—and Du Bois—the legendary African American sociologist and writer—might seem an unusual pairing. I argued that, on the contrary, they share the same way of thinking about the vicissitudes of being a member of a persecuted minority. For persecuted minorities, to know is to hurt, to exist is to be a problem.

Nechama Tec

I began by explaining my title, which I adapted from an anecdote in Kluger’s brilliant memoir Still Alive: A Holocaust Girlhood Remembered. In 1937—Kluger was about to turn six—her family summered in Italy. They had a car, rather unusual for the time, especially in Italy. Driving through the rural South, they pass another car with Austrian plates. The tourists wave to each other. Kluger is taken by the experience. She thinks, We wouldn’t have done that at home; we don’t even know each other. Writing many years later, she reflects:

I was enchanted by the discovery that strangers in a strange land greet each other because they are compatriots.

But this comforting nationalism, in which strangers become acquaintances by virtue of calling the same place home, would soon prove false and alienating. Kluger learned, along with the rest of Europe’s Jews, that being Jewish trumped being Austrian (or German or Polish or French or whatever). On her prewar holiday, Kluger enjoyed the experience of being a stranger in a strange land; just a year later, after the Anschluss, Kluger became a stranger in her own land.

To realize you are not at home in your home is shattering. The experience is powerfully ambivalent one, at once harmful and helpful.

To show how that might be the case, I referenced three Holocaust survivors: Kluger, Nechama Tec (born in Lublin in 1931 and hidden together with her family in a series of safe houses across Poland), and Sarah Kofman (born in Paris in 1934 to parents who had emigrated from Poland and who survived in hiding with a family friend she learned to call Mémé). Interestingly, all of these women later became academics: Kluger a professor of German, Tec of sociology, Kofman of philosophy.

(I’ll skip the potted bios, but I’m happy to say more in the comments if you’re interested.)

That brief orientation over, I divided the class into three and assigned each group one of the following passages, which we first read aloud together:

I found a small opening in the wall from which, unobserved, I could watch the girls at play. To me they seemed so content, so carefree, and I envied them their fun. Did they know that a war was on? At times, as I watched them, I too became engrossed in their games and almost forgot about the war. But the bell that called them back to class called me back to reality, and at such moments I became acutely aware of my loneliness. These small excursions made me feel, in the end, more miserable than ever. The girls in the boarding school were so near and yet so far. The wall that separated us was thick indeed, and eventually I could not bear to go near it.

—Nechama Tec, Dry Tears: The Story of a Lost Childhood (1982/84)

(Before we read, I explained the context. The scene takes place in 1940 or 41. Tec and her family are living in hiding in a disused part of a factory formerly owned by Tec’s father. The factory abuts on a convent school, a source of fascinated longing for Tec.)

In 1940, when I was eight or nine, the local movie theatre showed Walt Disney’s Snow White. … I badly wanted to see this film, but since I was Jewish, I naturally wasn’t permitted to. I groused and bitched about this unfairness until finally my mother proposed that I should leave her alone and just go and forget about what was permitted and what wasn’t. … So of course I went, not only for the movie, but to prove myself. I bought the most expensive type of ticket, thinking that sitting in a loge would make me less noticeable, and thus I ended up next to the nineteen-year-old baker’s daughter from next door with her little siblings, enthusiastic Nazis one and all. … When the lights came on, I wanted to wait until the house had emptied out, but my enemy stood her ground and waited, too. … She spoke firmly and with conviction, in the manner of a member of the Bund deutscher Mädchen, the female branch of the Hitler Youth, to which she surely belonged. Hadn’t I seen the sign at the box office? (I nodded. What else could I do? It was a rhetorical question.) Didn’t I know what it meant? I could read, couldn’t I? It said “No Jews.” I had broken a law … If it happened again she would call the police. I was lucky that she was letting me off this once.

The story of Snow White can be reduced to one question: who is entitled to live in the king’s palace and who is the outsider. The baker’s daughter and I followed this formula. She, in her own house, the magic mirror of her racial purity before her eyes, and I, also at home here, a native, but without permission and at this moment expelled and exposed. Even though I despised the law that excluded me, I still felt ashamed to have been found out. For shame doesn’t arise from the shameful action, but from discovery and exposure.

—Ruth Kluger, Still Alive: A Holocaust Girlhood Remembered (2001)

(The passage offers its own context; but I reminded participants that by 1940 the situation for Jews in Vienna was increasingly dangerous. Kluger’s father, a doctor who had already been arrested for seeing Aryan patients, had just fled for France (from where he was later deported to the Baltics and murdered); Kluger’s own deportation was less than two years away.)

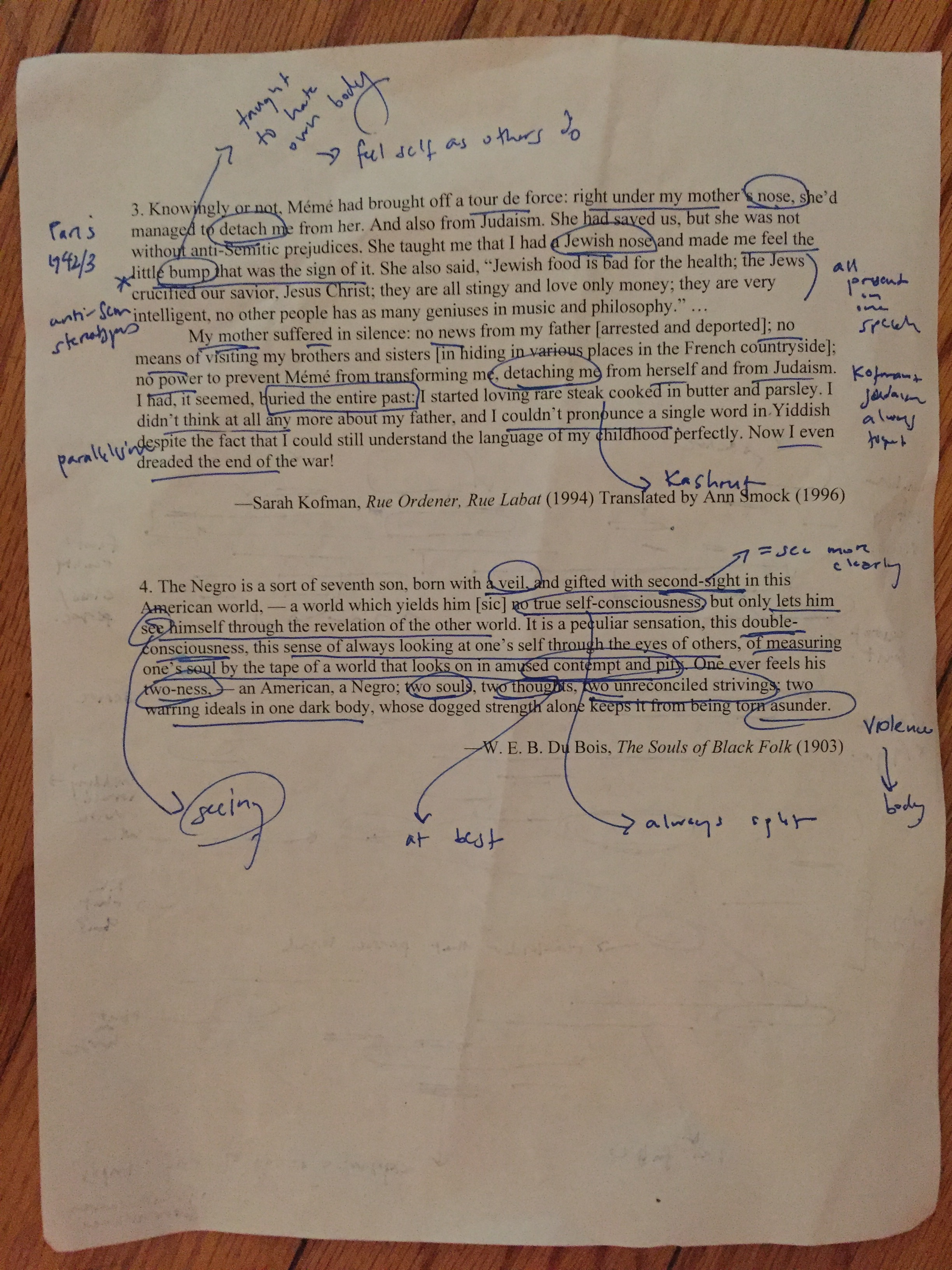

Knowingly or not, Mémé had brought off a tour de force: right under my mother’s nose, she’d managed to detach me from her. And also from Judaism. She had saved us, but she was not without anti-Semitic prejudices. She taught me that I had a Jewish nose and made me feel the little bump that was the sign of it. She also said, “Jewish food is bad for the health; the Jews crucified our savior, Jesus Christ; they are all stingy and love only money; they are very intelligent, no other people has as many geniuses in music and philosophy.” …

My mother suffered in silence: no news from my father [arrested and deported]; no means of visiting my brothers and sisters [in hiding in various places in the French countryside]; no power to prevent Mémé from transforming me, detaching me from herself and from Judaism. I had, it seemed, buried the entire past: I started loving rare steak cooked in butter and parsley. I didn’t think at all any more about my father, and I couldn’t pronounce a single word in Yiddish despite the fact that I could still understand the language of my childhood perfectly. Now I even dreaded the end of the war!

—Sarah Kofman, Rue Ordener, Rue Labat (1994) Translated by Ann Smock (1996)

(The passage, set in 1942 or 43, describes how Mémé, the woman who saved Kluger, also abused her.)

Sarah Kofman

Each group worked together to discuss the passages and answer two questions. The first was the same for everybody: Do we see self-awareness in this passage? If so, how?

The second was particular to the excerpt. I asked the Tec group to track the passage’s verbs. What can we learn about Tec’s experience when we pay attention to those verbs?

I asked the Kluger group to track the word “home” and its synonyms in this passage. What can we learn about Kluger’s experience when we pay attention to those words?

I asked the Kofman group to track two repeated words in the passage: “detach” and “nose.” What can we learn about Kofman’s experience when we pay attention to those words?

As the participants worked on their assignment, I wandered the room, eavesdropping and cajoling if the conversation seemed to falter. After seven or eight minutes, I brought the class back together and asked each group to report their findings (after reminding everyone that, since we’d all read the passages aloud, anyone could feel free to chime in at any time).

They did well! If you like, you can take a minute to think about how you’d answer the questions.

My annotations

Here are some of the things we noted:

Tec shows us both the appeal of fantasy and its cost. Spying on the children lucky enough to still be living ordinary lives takes her out of her situation, allows her to remember another life, even to almost forget the war. But the school bell that rings for them but not for her recalls her to reality. And that reminder is painful: she feels even worse than before, to the point where she eventually gives up her voyeurism. I’m always struck by “these small excursions”—such striking and unusual phrasing. What does an excursion imply? A vacation, a trip, a holiday, students will say. An adventure, but a safe one. Yes, I’ll add, an inconsequential one (a sense furthered by the adjective “small”). Tec is an explorer, but not, in the end, a successful one. She can’t keep going back to look at the childhood she no longer has. Excursion implies choice; yet this fantasy too fails her, just as the active verbs of the beginning of the passage (to find, to watch, to envy—things Tec herself chooses to do) are replaced by the experience of states of being (become engrossed, become acutely aware—things that happen to Tec).

The story of Kluger’s clandestine, dangerous trip to the movies (itself a salutary reminder for participants of how thoroughly Jews were shut out of ordinary life) centers on exposure. The “ex” prefix here, as in her use of “expelled” and Tec’s “excursion,” gestures to a desire, expressed at the very level of phonetics, to get out, to escape. Kluger tries to hide in plain sight, but the effort fails. Significantly, it is her next door neighbour who finds her out, showing us both how intimate persecution is, and how much, in this context at least, it functioned through an undoing of everything home should stand for. (To sell the point, Kluger uses many variations of the word home: I’m especially struck by her decision—not unidiomatic, but also not typical—to describe the theatre as a “house.”) Just as persecution makes home foreign, so too does it pervert justice. The baker’s daughter is right when she scolds Kluger for breaking a law: it’s easy for us to forget that Nazi persecution was legal. Kluger’s world has been turned upside down (her use of “naturally” is thus ironic); only she herself, her personality, her determination, offers the possibility of continuity. She is forbidden to go to the movies, so “of course” she goes. That’s just who she is. But the consequences of that persistence (nearly being turned over to the police) suggest that the idea of being true to one’s self is for Kluger as much a disabling fantasy as Tec’s spying.

Kofman similarly struggles to understand who she is. The figurative nose in her first sentence (and I’m cheating here, since we were working with a translation, and I don’t know the original) is echoed, then amplified by the literal one that Mémé so disparages. As a group we marveled, if I can put it that way, at Kofman’s anguished situation: out of a complicated mixture of gratitude, internalized self-hatred, and adolescent rebellion against a difficult mother, who, to be sure, is herself in an unbearably difficult situation she falls in love with a woman who turns her against herself. Mémé teaches Kofman to hate her own body and her own identity, by making her experience herself as others do. In that sense, she turns Kofman into someone who must live in bad faith. Yet, as we noted, the repetition of “detachment” inevitably carries with it a reminder of attachment: in describing what she has lost Kofman indirectly reminds us of what she once was. And we speculated that Kofman’s similarly indirect presentation of Mémé’s litany of anti-Semitic canards (where even the compliments are backhanded) implies a kind of resistance on her part to the older woman’s actions. It is unlikely, I suggested, that Mémé said all of these things at once, in a single sentence, as Kofman presents it. Which implies she has arranged the material: by piling the attacks on, she is inviting us to see them as ridiculous, contradictory, unhinged. But Kofman’s critique is retrospective. At the time, her position is utterly confused. Witness her (classically hysterical) aphasia—able to understand her mother/father tongue, but no longer able to speak it. Years later, Kofman eventually throws Mémé over, even refusing to go to her funeral. The “good mother” in the memoir—well worth reading—turns out to be neither of the two women she is caught between but rather Frenchness itself: the language & culture Kofman becomes so adept in, able to wield rather than submit to.

Having facilitated discussion, and with time drawing short, I emphasized that resistance and rejection are intertwined in these passages. Resistance takes the form of self-knowledge.

W. E. B. Du Bois

To understand the implications of that double position, I had us turn to a thinker from a different tradition. I read aloud the last passage on the handout:

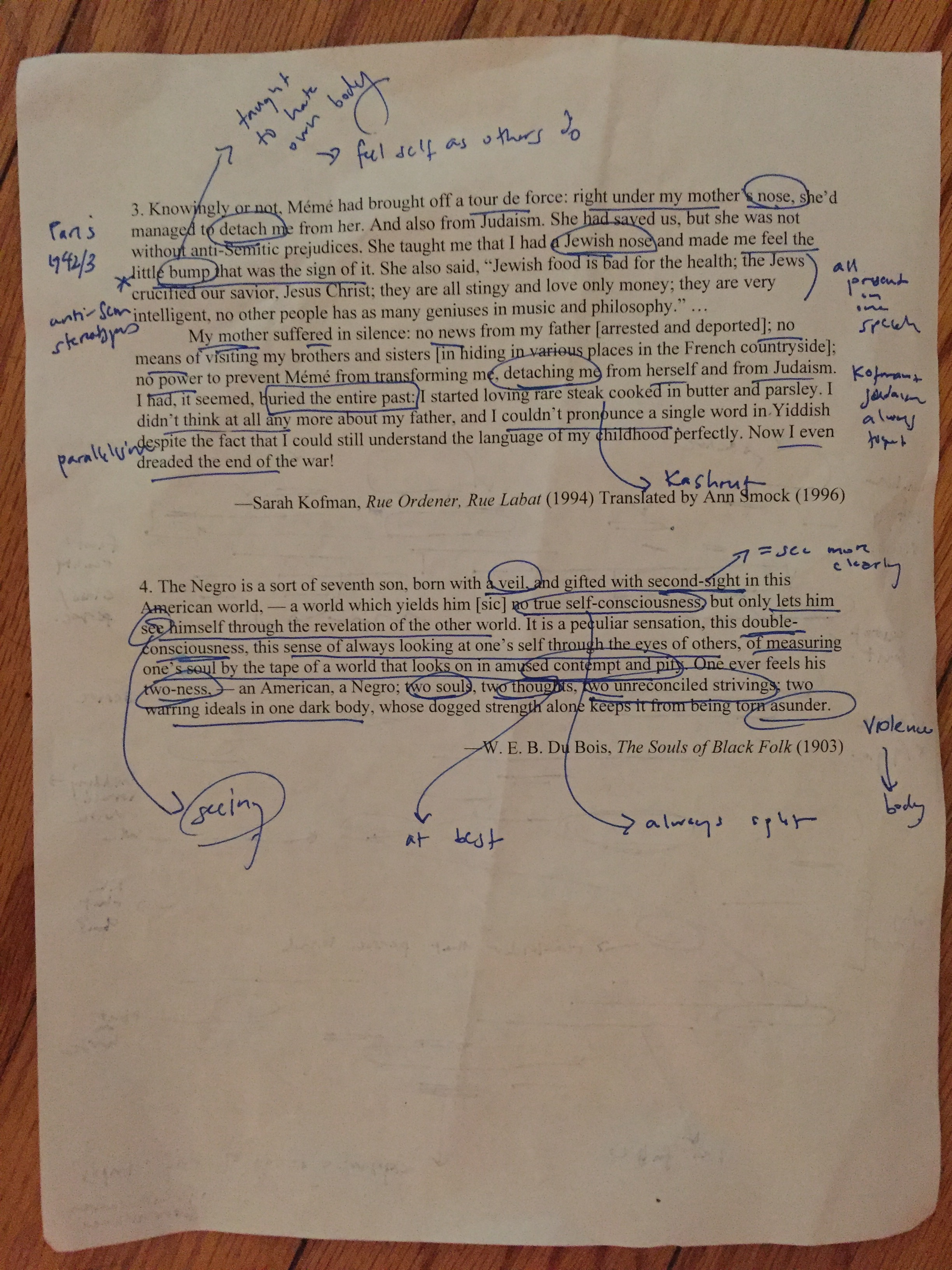

The Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world, — a world which yields him [sic] no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

—W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

Then I defined that consequential term double-consciousness: it’s what results when we have to define the self through the eyes of others. (I always use the example of Canadian identity, because it’s relatively low stakes and I can try to be funny with it: when Canadians think about what it means to be Canadian, as they often do, they usually begin, “Well, we’re not Americans…” In my experience, Americans seldom think about what it means to be American. They certainly don’t say, “Well, we’re not Canadians…” Which is because in geopolitical as well as cultural terms, America is dominant; they set the terms of understanding. The tape Americans use to measure themselves has been made to measure them.)

Minorities, Du Bois argues, typically define themselves in terms set by the majority. A significant result of this claim is that there is something valuable about that position of double-consciousness, for it is by definition a critical position. As Kluger explains in her memoir, her earliest reading material was anti-Semitic slogans, which gave her “an early opportunity to practice critical discrimination.”

The position of the majority or the dominant is properly speaking stupid, because it never has to translate its experience into terms given by someone else. It need never reflect. That is the definition of privilege.

But double-consciousness isn’t just enabling. To be in that position, to be a minority, specifically a persecuted minority like Jews in fascist Europe or Blacks at any time in American history, including the present, is to be at risk. Critical positions are precarious, dangerous, even intolerable—not just psychologically but also bodily. Think of Du Bois’s resonant, pained conclusion: to inhabit double-consciousness (to be at home in the idea of never being at home) is to feel “two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” Torn asunder. How can we read that and not think of lynching, or gassing, or any of the myriad ways minority bodies have been and continue to be made to suffer?

We were out of time. So I could only end by saying that the reason I had us to read Du Bois alongside Holocaust survivors was to think intersectionally. In terms of double-consciousness, minority experiences are more similar than different. And I wanted participants to think about the lesson for us today from these (to them) very old texts. To ask these questions: If we are a member of a minority, can we harness the power of double-consciousness and not be crushed? If we are a member of a majority, can we become self-aware enough not to harm, whether knowingly or unknowingly, minorities?

Can we be at home without being smug? Can we be self-aware without being strangers?