A difficult semester finally came to an end. After all the ends were tied up (always takes longer than I expect) I sort of collapsed, emotionally and bodily. Had some tough days there, but to my surprise a family trip to Houston put me on a better keel—not least by filling my belly with good food. Through it all I was reading, to whit:

Kaoru Takamura, Lady Joker [Vol 1] (1997) Trans. Marie Iida and Allison Markin Powell (2021)

A 600-page crime novel set in 90s Japan? A positively Tolstoyan character list, covering many different institutions and social classes?? A book willing to take its time, building terrific suspense through care and attention??? And it’s only volume one, there’s a whole other 600-page second part???? (Cue that meme of the guy, I don’t even know who he is, with his eyes bugging out in increasing ecstasy.) Hell to the yeah. I spent the last part of November and the first days of December with Takamura’s opus, time that was richly rewarded.

At the heart of Lady Joker are five regulars at a racetrack: an unappreciated cop, a Zainichi banker (a descendent of Koreans who came to Japan before WWII, and much denigrated, I learned), an asocial welder, a truck driver with a disabled daughter (her nickname gives the book its title), and the owner of a drugstore whose grandson has died in mysterious circumstances that involve a story of prejudice from the past, centering on the bukaru community (an ostracized caste whose members were once allowed to practice only “unclean” or “defiled” professions: see how much you’ll learn from this book?). The men come together to commit a crime: a perfect setup because other than their weekly pastime and their resentments they have nothing in common.

At its heart, Lady Joker is simple: a bunch of misfits who happen to have specialized skills and a lot of patience get together to enact revenge on a society that deems them expendable. Their plan succeeds—at least, it seems that way: like their creator, these guys are playing the long game—but it also seems inevitable they’ll get caught. Which is gonna suck. But so is the thought that they wouldn’t. Which is a testament to how evenhandedly Takamura depicts her characters.

Lady Joker isn’t an easy read. (I might not have persevered had I not been reading it with a friend.) Its challenges are many: the painstaking depictions of the processes that make organizations, whether a company, a newspaper, or the police (as another friend whom I had pressed the book on joked, “Now I can run a brewery in 1990s Japan); the cast of characters (I had to refer back to the list at the beginning all the time); the references to Japanese history and culture. It contains at once so much exposition and none at all. Central, dramatic events are told indirectly; the greatest suspense comes from details like a missing document in a company’s archive or a changed roster during a police investigation, which unexpectedly brings two characters together. Throughout, Takamura—who apparently has written many books; may the rest be translated soon—returns to the question of whether people can find meaning in working for an organization. On the face of it, the book indicts Japanese work culture. But it also believes that work is the most meaningful thing in life. There’s basically no domestic life in this book, no love interest, no hobbies or relaxation. (Even the horse races don’t seem to give anyone much pleasure.) Do the misfits want to overthrow the system? Or do they want in? Maybe all will be revealed in volume 2!

Props to translators Iida (perhaps best known to many of us as Marie Kondo’s translator on the Netflix show) and Powell for their heroic work, and to Soho for taking a risk in publishing this book. Make it worth their while, people!

Stephen Spotswood, Fortune Favors the Dead (2020)

Lilian Pentecost is the most famous PI in New York City in the late 1940s, taking on cases that baffle the police and always looking out for the oppressed. A mind like hers needs no help—but her body, well, that’s a different story. As much as she tries to hide it, her multiple sclerosis makes some parts of her job hard. Which explains why, when she runs into a young woman at a construction site in midtown late one night, she takes her on as an assistant. It doesn’t hurt that the woman, Willowjean (Will) Parker, has just saved her life by throwing a knife into the back of the crooked foreman who was about to kill her. Where would a slip of a girl like Parker have learned to throw a knife like that? In the circus, of course, where she picked up all kinds of skills to add to the ones need to survive life as a teen on the run from an abusive father. Parker, who was at the construction site moonlighting as a watchman, is ambivalent about leaving the circus life, but the chance to work with Pentecost is too good to pass up. She intimates that her passion for justice—no, not passion, zeal; it hounds rather than inspires—can be turned to better ends.

And thus the Pentecost and Parker duo is born. I gather Spotswood is paying homage to Rex Stout (unaccountably as-yet unknown to me), but he’s also doing his own thing: showing us an America in which women have been asked to take on bigger roles while the men are at war but quickly seeing that opportunity fade as the boys come home; and emphasizing queer and disabled characters without making a big deal about it. Of course, there’s also a case to solve—and solve it they do. But doing so leads to a bigger mystery; Spotswood is setting himself up for a long arc.

Having now read all three P & P titles in quick succession, I can say these books are the real deal. Zippy writing, clever plots, heartwarming but not cloying. Why isn’t there more buzz?

Lion Feuchtwanger, The Oppermanns (1933) Trans. James Cleugh (1933) revised by Joshua Cohen (2022)

Meat and drink to me. I fell into the story of the Oppermann brothers, their name known across Germany thanks to the chain of furniture stores founded by their grandfather in the aftermath of German unification. I marveled, too, at this artistic testament created in the teeth of persecution: Feuchtwanger wrote it in only nine months, from spring to fall 1933. (In this regard, if not otherwise, I was reminded of Alexander Boschwitz’s The Passenger.) By the time it was published he could no longer live in Germany.

Between them, the brothers command respect across German society. Martin runs the business, making bourgeois furnishings available to the petit-bourgeois masses. Edgar is a surgeon, the inventor of the Oppermann technique, which has the best success rate in the world at curing an unspecified condition. And Gustav is the intellectual, the lover of women and life, who has for years been working on a biography of Gotthold Lessing, though not especially diligently. The book begins when Gustav turns 50 at the end of 1932; although it moves between the siblings, he remains its focus. (There’s a sister, too, Klara, though she’s less important than her husband, a foreign Jew who avoids the fate of the others because he happens to have American citizenship; perhaps for that reason he is the most prescient character, warning that the Nazi fever will not break any time soon.) The most significant subplot concerns Martin’s son, Berthold, who blithely resists the bullies among his schoolfriends, but can’t do so when a strident Nazi is appointed as his teacher, with tragic results.

Feuchtwanger describes the many ways German Jews responded to the first year of Nazi rule: accommodation, dismissal, betrayal, fear, highminded but ineffective refusal, despair, suicide, and exile. The latter is the tactic pursued by Gustav, who after denying that anything could happen to someone as identified with German culture as himself, is brought to reality when the SA turns over his house, something that happened to Feuchtwanger himself.

Gustav escapes to Switzerland and the south of France, living the good life in Ticino and the simple life in Provence, but he is haunted by reports smuggled out of Germany exposing the concentration camp system (quite different from the extermination centers set up in the east starting in 1941 that American readers might be most familiar with). He makes a daring, preposterous decision and returns to Germany under false papers with the aim of joining the resistance he believes must exist. In some remarkable, if also rather artificial scenes (Feuchtwanger knew the least about this material) he is arrested and deported to a camp, which he survives, but not for long. [Oops, spoiler, sorry.] As Joshua Cohen puts it in his useful introduction to this modified translation, newly released in that lovely McNally Editions series, Gustav’s noble or ridiculous decision can be understood as his attempt to live out that saying from the Talmud that is the book’s primary leitmotif, “It is on us to begin the work. It is not upon us to complete it.”

My friend Marat Grinberg has a book coming out later this year on what he calls “the Soviet Jewish bookshelf”—the books that Jews in the Soviet Union, especially post WWII, relied on to give them a sense of identity. He’s told me that Feuchtwanger in general and this book in particular had pride of place on that shelf; I can’t wait to read more about this because I can’t figure out why Oppermanns would appeal so strongly to those readers. Because its social realism and antifascism were ways to smuggle affirmations of Jewishness into a society where religion was officially forbidden and Jewishness persecuted? And yet the Jewishness of Oppermanns is so much that of assimilated German Jewry that it’s hard to imagine Soviet readers identifying with it. Not to mention that Feuchtwanger’s almost existentialist insistence on individual ability doesn’t seem in keeping with Soviet values (though maybe that was the appeal). At any rate, Cohen ably suggests how the book might resonate with contemporary readers even as he rejects facile comparisons between the fascism of the present and that of the past.

Shelley Burr, Wake (2022)

Superior Australian Outback noir—I guess that’s a thing now—that left me wondering exactly what happened at the end (in a good way). Two storylines intersect—one about a woman whose twin sister disappeared one night from the family home, and whose case became a media circus; the other about a man who solves cold cases after having had to drop out of police academy to look after his sister when their abusive father was finally put in jail. The man wants to solve the woman’s case; his motives are more complex than he at first lets on. Damn good stuff from Burr in her debut, though I take the point the brilliant Beejay Silcox makes about the limitations of the genre Wake seems to be a part of. I’m glad this was published in the US, though, and I’ll read Burr’s next book.

Stephen Spotswood, Murder Under Her Skin (2021)

Pentecost and Parker are called to rural Virginia when Parker’s mentor from the circus—the man who taught her everything she knows about how to throw a knife and more besides—is accused of murder. Along the way, a delightful new character is introduced. Maybe not as perfect as Fortune, but still light reading manna.

Michelle Hart, We Do What We Do in the Dark (2022)

Good stuff, from the title onward. Mallory is a freshman at a college on Long Island whose mother has recently died (her oblique relationship with her sad and bewildered father, though only sketched out at the margins of the story, is one of the book’s many pleasures). Mallory is lonely, always has been, it seems. And yet she finds being with others difficult—until she meets a female professor, an adjunct who teaches children’s literature and a renowned writer of children’s books. The woman, who is German, is brusque, self-possessed, worldly: everything Mallory wants to be. Startlingly to Mallory, and possibly to the woman herself, the two embark on an affair, at once torrid and composed, which ends when the woman’s husband returns from a semester at a more prestigious university. The woman sees in Mallory a kindred spirit: someone who keeps things to herself. The woman is the one who speaks the phrase that gives the book it’s title, though weeks later I’m still wondering if “what we do in the dark” is the predicate of doing or if “in the dark” modifies the seeming pleonasm “we do what we do.”

Either way, the affair takes up only a small part of this small book, but it colours Mallory’s life, shaping many of her later personal and professional decisions. There’s a pained and painful denouement, but the most interesting material concerns Mallory’s childhood best friend, Hannah, with whom she becomes a little obsessed, and Hannah’s mother, who befriends Mallory when her daughter goes off to college—though that is a poor word for their excessive, intimate, and mutually exploitative relationship—only to drop her when Hannah comes home for the summer.

For more on this novel of female (over) identification and queer desire (complete with happy ending!), I recommend Scaachi Koul’s illuminating NYT review. I especially like Koul’s point that the erotic thriller has taken on new life in contemporary lit fiction: “less about the horror of sex and romance and more about the thrill of quiet despair and ruin.” She cites Sally Rooney; I’d add Naoise Dolan. Maybe you can name others.

I would never have read this—like all the new books it has one of those totally forgettable but apparently instagrammable covers; nothing would have made me pull it off the library’s new books shelf—had it not been for Lucy Scholes’s recommendation. It won’t be on my top-ten list, as it was hers, but I liked it plenty. Hart is one to keep an eye on.

Claire Keegan, Walk the Blue Fields (2007)

A let-down compared to the magic of Small Things Like These. Each of these tales of despair and anger in rural Ireland (excepting one unaccountably set in Texas: a misfire) offers something memorable. Yet each came up short for me. “The Long and Painful Death,” about a writer who arrives for a residency at the cottage Heinrich Böll made famous in his Irish Journal (1957) where she is accosted by a hostile scholar, might be the most completely satisfying, though it becomes too cheaply meta for me at the end. I loved the title story most—it has that real Alice Munro-William Trevor-whole-lifetime-in-a-few-pages vibe—though there’s an important Chinese character that I bet Keegan would write differently now. I often like stories that are a little messy, but these ones failed to win me over. If I hadn’t been looking for new material for a course I’m teaching next semester, I probably wouldn’t have finished.

Rose Macaulay, Dangerous Ages (1921)

Having read a grand total of two of her books, I hereby pronounce Rose Macaulay to be a weird and interesting writer. I use the last adjective advisedly, after the model of Gerda, a 20-year-old poet and, lately, social reformer, who, laid up for weeks with a sprained leg, lies on the sofa and reads. Poetry, of course. Works of economics too. Both are “about something real, something that really is so. … But most novels are so queer. They’re about people, but not people as they are. They’re not interesting.” Today, it’s Dangerous Ages that seem queer: a family saga that’s only 200 pages, confines itself to a mere year or so, and ignores its male characters. No saga at all, you might say. And yet I’m not sure what else to call it.

Focusing on the women in four generations of a family in 1920s England—Gerda is in her 20s, her mother Neville in her 40s, her mother, Mrs. Hilary, in her 60s, and her mother, known to all as Grandmama, in her 80s—the novel confirms what Mrs. Hilary’s psychoanalyst says: “All ages are dangerous to all people, in this dangerous life we live.” (So interesting that it’s the hidebound Mrs. Hilary, at a loss in her widowhood with her children grown and chafing against her neediness, who finds succor in analysis, even as she rejects its language of desire, thrilled to finally be seen as important.) I struggle to place Macaulay in the writers of her period—I welcome your comps—but at times, reading this book, I was reminded of Tessa Hadley: the dramas of relationships, at once ordinary and all-encompassing; the shifting alliances over time in a family. But Macaulay is a little archer and much cooler. A book I like more in retrospect than I did reading it.

Ramona Emerson, Shutter (2022)

Rita, the lead in Emerson’ debut, is a forensic photographer for the Albuquerque police, a job that puts her at odds with many in the Navajo nation, including her grandmother, an indominable and loving woman who raised Rita and bought her first camera. All of these things are true of Emerson herself (she worked with the Albuquerque PD for 16 years). No surprise then that the book started as a memoir. But it became a novel when Emerson introduced something presumably not from her own life: Rita sees dead people, always has. Which makes her job hard, especially when one of the ghosts, a woman whose death was ruled a suicide, violently demands that Rita investigate what she insists was a murder.

Shutter moves back and forth between past and present—each chapter is tagged with the camera most important to Rita at the time—and honestly is more interesting as a coming of age story than a crime novel. The perp is obvious (even I knew it, and I never get these things right). Wouldn’t surprise me if Emerson turned this into a series, and that would be ok, since her plotting will surely improve, but I wouldn’t mind reading that memoir.

Roy Jacobsen, The Unseen (2013) Trans. Don Bartlett and Don Shaw (2016)

God, I loved this book. And it’s only been sitting on my shelf for like five years. On a little island somewhere in the way north of Norway named Barrøy lives a family named after it (or maybe the island is named for them). The time is unspecified, probably the early twentieth century: there’s a reference to a distant conflict that I take to be WWI, but the point is that such things barely impinge on life on Barrøy, which is almost entirely concerned with survival. The family is made up of Hans and Maria, their daughter Ingrid (only three when the novel begins), Hans’s sister, Barbro, and their father, Martin. Barbro is known to be “simple” but that doesn’t stop her from raising a son she (with surprising lack of scandal) conceives with a visiting Swedish labourer.

Ironically, The Unseen is mostly about the tangible, endless work of living in a harsh climate. There’s so much to do: peat to cut, eiderdown to card, cows to milk, eggs to collect, and of course fish to be caught. (In addition to line-fishing in the lee of the island, Hans, who has a share in his brother’s fishing boat, spends the first three or four months of the year even farther north, risky work that provides most of the family’s income). I do love a book that teaches me how people do things—I learned a lot about fishing nets, and loved every minute of it.

The family is at once almost brutally isolated and connected to a local network: there are other islands nearby (Maria was born on one), and a town on the mainland with a store, the church, and the school Ingrid attends for a time. (The crossing from the island is lovely in fine weather; damn near impossible in bad.) This is one of those nothing happens/everything happens books, where the everything is life itself. The characters are not especially demonstrative with each other but so lovable to readers. I was invested in them, and gasped at a couple of especially dramatic moments. (I am a great gasper.) Modernity does begin to make itself felt as the book goes on—a little tug collects milk once a week and brings mail and other news. And I suppose the wider world will come calling in the three books Jacoben has since been compelled to write about this story, especially for Ingrid. If I’m right, then The Unseen will be like the first part of Lawrence’s The Rainbow, far and away my favourite part. I’m sentimental about “timeless, simple” remote worlds—though the book, I’ll note, is not. Or maybe only a little. Anyway, I’m all in for the rest of the series. And by the way, Bartlett and Shaw have done amazing work here. In addition to all the nautical terms, they’ve had to deal with the dialogue, which is in dialect. The translators have transformed it into a version of northern English or Scots. They make no claim to authenticity but they also don’t resort to pastiche. Interesting!

I already bitched about this on Twitter, but I started this book in an attempt to read what I already own and ended up ordering three more. Dammit!

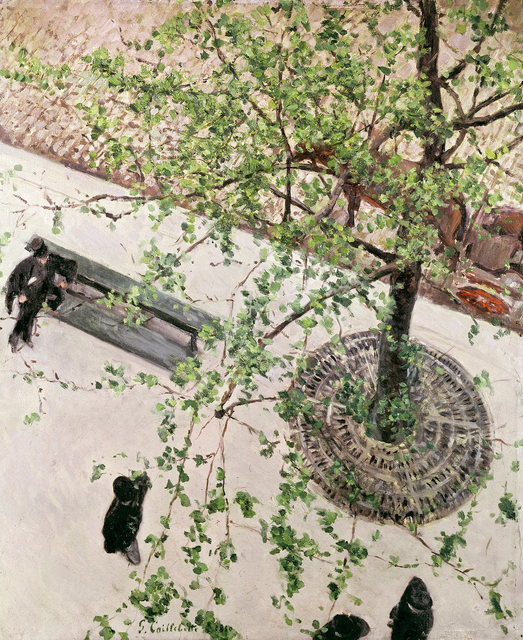

Penelope Mortimer, Daddy’s Gone A-Hunting (1958)

Good but ghastly. Mortimer’s novel of a woman pushed into a terrible marriage that has left her adrift in the Home Counties now that her daughter has gone up to Oxford and her sons are at boarding school makes Jean Rhys look positively joyful. I had Rhys on the mind because the plot of Daddy centers on unwanted pregnancy. The only reason Ruth married her husband, a tyrannical, philandering, self-pitying dentist (mercifully in London during the week), is that she got pregnant. Now that child, her daughter Angela, first glimpsed in the novel clinging to an unknown boy on the back of a motorcycle as Ruth returns from the journey to London to take the boys to school, a fitting metaphor for their cross purposes, is herself pregnant, from the boy on the bike of course, a fellow student who imagines himself sensitive but is just a small version of Ruth’s husband. Angela wants to get rid of it, but she also doesn’t want or doesn’t know how to do anything about it. Ruth is desperate for her daughter to avoid her own fate, though she’s unwilling to tell her daughter about their shared situation. The mechanics of arranging an abortion—illegal at that time in Britain—are fascinating; this makes a fascinating comparison to Annie Ernaux’s story of her own experiences a decade later in France as told in her book Happening.

I mention Rhys because her absolutely brilliant novel Voyage in the Dark centers on abortion. Rhys’s masterpiece is a cruel and despairing book—but also an enlivening one, no doubt because of the (ineffectual) self-awareness of the first-person narration. Ruth is harder to access, since her story is told in (more or less close) third-person. Which means a better comparison might be to Doris Lessing, whose novels of women finding their way in a misogynist society were in full spate by 1958. Lessing is a more intellectual writer than Mortimer, but Angela is the kind of character Lessing would often center in her writing. Admittedly, I was having a bad time mentally in the last days of the year as I read this book, so the story of a woman ground down by hypocrisy, condescension, and lack of sympathy was hard-going. Even if my mood had been more even-keeled, though, I think I would have found this a cold, distressing book. I mean, listen to Ruth’s reflection, late in the novel:

It occurred to her that dishonesty had never been unconscious, accidental; it has always, as now, been deliberate, the only way of survival. The opportunity to speak the truth, to use the language taught you in childhood, never arose.

Note the omission of the possessive before “dishonesty”—not hers but everybody’s. Are Mortimer’s other books this unhappy?

Happy with what I read. Lady Joker is truly something. Feuchtwanger and Jacobsen were maybe the highlights. The Hart has really stuck with me. And those Spotswoods are good stuff. What about you all? How did your year end?