A while ago I convinced Scott of seraillon to help me host a discussion of Giorgio Bassani’s The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1962). I hope others will join in, and as they do I’ll link to their posts here:

Meredith at Dolce Bellezza

Jacqui at Jacquiwinejournal

Grant at 1streading’s Blog

Nathaniel Leach

I’ve written up my thoughts on what for me are some of the key aspects of this fascinating and beautiful novel. Scott has responded and added some of the issues that most struck him. In a separate post at Scott’s blog we’ll reverse the roles.

Thanks, Dorian! Since you’ve divided your thoughts into discrete sections, I’ll respond in italics after each one.

First, a brief summary of the book:

On a Sunday in April 1957, the unnamed narrator is on a day trip from Rome with friends. They unexpectedly end up at some Etruscan tombs. A little girl in the party asks her father why ancient tombs are not as sad as new ones. With those who have been dead so long, he replies, it’s as if they never lived. To which the girl rather precociously (one of the book’s few false notes) responds:

‘But now, if you say that’, she ventured softly, ‘you remind me that the Etruscans were also alive once, and so I’m fond of them, like everyone else.’

He doesn’t say so directly, but the narrator seems to be moved by these remarks. We might even say that he is unsealed. The Etruscan tombs remind him of the grandiose tomb of the Finzi-Contini family in his native Ferrara. Perhaps emboldened by the girl’s insistence that everyone who is dead deserves to be remembered, the narrator thinks of the fate of Italy’s Jews during the war. He tells the story—a story it seems he has held inside for a long time: that’s what I mean by his coming unsealed—of his relationship to the Finzi-Contini family in the years before the war. (Interestingly, he only tells us, not his traveling companions. I’m not sure what to make of this, other than to suggest that, as befits this tightly wound character, even emotional catharsis is restrained.)

Beginning with the end, the narrator explains that the story of the Finzi-Continis is one of catastrophe. Of all the members of the family the narrator “had known and loved” only one had managed to find the eternal rest promised by the tomb:

In fact the only one buried there is Alberto, the older son, who died in 1942 of a lymphogranuloma. Whereas for Micòl, the second child, the daughter, and for her father, Professor Ermanno, and her mother, Signora Olga, and Signora Regina, Signora Olga’s ancient, paralytic mother, all deported to Germany in the autumn of ’43, who could say if they found any sort of burial at all?

The plot then shifts to the narrator’s childhood, highlighting his occasional encounters with the Finzi-Continis, before moving forward to 1938 and the promulgation of racial laws in Italy. When the wealthy Jews of Ferrara are forced out of the tennis club, Micòl and Alberto invite the younger set to play on the court on the estate surrounding the family home.

The narrator, who had always been drawn to the mysterious family, quickly falls in love with the Finzi-Continis and especially with Micòl, and over the following year they become increasingly close but never intimate. Micòl evades and eventually rejects the narrator. He is distraught and eventually forces himself or is forced to get over it. And then the war begins and this idyllic (if that’s the right word) time in the narrator’s life ends. That’s the story he wants to tell—the story of the days in the garden of the Finzi-Continis’ estate—not the story of what happened to them all later.

When I put it like this, the book might sound dull, but I found it completely riveting. Whoever chooses to read along with us in the coming days will help us build a picture of the novel. For now I want to talk about three things that struck me, and then mention a fourth.

I too found The Garden of the Finzi-Continis beautiful and riveting – so much so, in fact, that I’ve now read it twice since January, first in the Jamie McKendrick translation and now in the translation you read by William Weaver. I can well understand why this could be someone’s favorite novel; it is moving, exquisitely constructed and has a delicacy and sense of closeness to lived experience that few novels attain from one end to the other. Both times I’ve read it I came away unable to think about much of anything else for days.

Bassani’s choice to place his “end” of the novel at the beginning, the revelation of the fate of the Finzi-Continis, signals to the reader that the author’s interest lies not in depicting the horrors of the Holocaust but elsewhere: in the world(s) that it destroyed. One might argue that the novel shouldn’t be categorized as “Holocaust literature” because it deals more directly with Italian Fascism, but I’d counter that Bassani is aiming precisely at overturning the sentiment that if Mussolini had not formed an alliance with Hitler, the country’s situation might have been tolerable. Something of this view gets conveyed in the intense political discussions the narrator has towards the end of the novel with his friend Malnate, one of the novel’s only non-Jews, but Bassani clearly wants to lay bare Italian culpability. For all of the peace that Bassani portrays within the walls of Edenic garden of the Finzi-Contini family, he also provides increasingly palpable glimpses of the hell that is growing beyond the garden walls, of the insidious, creeping intolerance and oppression that are alluded to subtly but frequently for much of the novel. For me this worked brilliantly – focusing on the bright lives at the center of an encroaching darkness rather than on the darkness itself. At the end one feels – but only afterwards, after the gentle impression of the final words have subsided – the colossal weight of all that has been pressing inward. The effect is devastating.

I. (Jewish) Outsiders

I really love books about outsiders who fall into (or maybe insinuate themselves into) worlds that are different—and, in their perception, better, richer, more enlivening, more satisfying—than their own. L. P. Hartley’s The Go-Between is a fine example. Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty is another.

I think I’m drawn to this scenario because, as a child of immigrants, I was tasked with helping my parents find their way in a new place. At the same time, I wanted to escape that role by finding worlds or social situations that were just for me. Literature has of course been for me the most important and all encompassing of those worlds. But my decision to move to another country is another example as is, more pertinently to Bassani’s novel, my conversion to Judaism.

I fell in love with Judaism for many reasons, mostly generous and anything but self-serving, but certainly one reason was the sense I had of it as a kind of refined minority. I realize this way of thinking verges perilously close to anti-Semitic stereotypes of secret cabals. But I understood the narrator’s attraction to—what he calls his “deep solidarity” with—the Finzi-Continis. The comparison I’m making is inexact. The narrator isn’t a Gentile, drawn by some sort of philo-Semistism to this Jewish family. No, he’s Jewish too. So in what sense is he attracted to something other or foreign in the Finzi-Continis? The Jewish community in the Ferrara of the novel is small—a handful of families—but as in all Jewish communities (and the smaller they are the truer this seems to be) divisions are as important as similarities.

In his introduction to the Everyman Edition, Tim Parks notes, “One of the curiosities of Bassani’s writing is that, while deploring persecution, he actually seems to relish the phenomenon of social division, that fizz of incomprehension that occurs when people of different cultures, backgrounds, and pretensions are obliged to live side by side.” I agree, though “deploring” seems too unequivocal, too dutiful, too mildly liberal and progressive for Bassani’s narrator, who is a slippery figure.

At any rate, the narrator’s family prides itself on being modern. The father joined the Fascist Party already in 1919. That might sound crazy to us, but Italian fascism was not initially anti-Semitic and might never have been had Hitler not pushed Mussolini in that direction, leading to the Nuremberg-style racial laws of 1938 that I mentioned in my plot summary.

The Finzi-Continis, by contrast, are conservative; Professor Ermanno refuses to join the Fascists, not out of any anti-Fascist or progressive/communist/socialist conviction but because he doesn’t want to join anything, not least the modern world. (It’s interesting that Micòl more than anyone else in the family shares her father’s views, more than her brother, that’s for sure, who is all about his gramophone and modern design, though Micòl also avails herself of certain privilege of modernity, like taking a university degree for example.)

Yet the narrator’s family and the Finzi-Continis are united in their form of worship: they belong to the Italian rather than the German synagogue (these differing congregations meet on different floors of the same building, a wonderful example of what Freud called “the narcissism of small differences.”) I’m confused by Bassani’s distinction here: I think it might be something like Orthodox (Italian) versus Reform (German) (Reform Judaism started in Germany in the 19th Century), but I’m not sure. Later, the Finzi-Continis and one or two other families (but not the narrator’s) decide to worship at even more exclusive synagogue (they call it the Spanish). I wondered if the suggestion was that they were Sephardic rather than Ashkenazi. Can anyone shed light here?

This wonderful essay by Adam Kirsch is smart on the paradoxical function of Judaism in the novel. He doesn’t explain the different congregations, but he has a lot to say about how the Finzi-Continis are positioned as “the Jews of the Jews,” an elite within an elite. The narrator’s father is convinced that the Finzi-Continis are in fact anti-Semites, adducing as proof their rejection, or, more accurately, lack of interest in the rest of the Ferranese Jewish community, as symbolized by the walls that surround their estate.

And yet the narrator’s father also thinks it’s embarrassing, even wrong, to be too devoutly or overtly Jewish: he barely speaks Hebrew, knows only a little of the liturgy, thinks of himself more as a freethinker than anything else. And yet that doesn’t contradict his strong sense of being a Jew, and his conviction that all Jews share a kinship he faults the Finzi-Continis for rejecting.

This sort of complicated emotional response—veering between pride and self-loathing—manifests itself in the narrator too, as in the scene where he runs into a Jewish boy of his own age: “Rapidly, between him and me, there passed the inevitable glance of Jewish complicity that, with anxiety and disgust, I had already foreseen.” The complicity might be good, but the anxiety and disgust sure aren’t.

The narrator remembers how, as a child, he would gather with the rest of his family under his father’s talit (prayer shawl) for the benediction. Because the shawl, which had belonged to the narrator’s grandfather, is so old and full of holes, the narrator is able to look out from, perhaps even to plot his escape from, what in the words of the blessing is the loving embrace of the family.

And what he looks out at is of course the Finzi-Continis performing the same ritual. He is drawn to the father—a scholar, a mild man, perhaps ineffectual but, we learn, genuinely kind, someone who will eventually become almost a colleague to the narrator—but even more so to the children. Yet where Professor Ermanno is the emblem of everything the narrator wants (what he calls “culture and rank”), his children, Alberto and Micòl, are at once more appealing and more off-putting:

I looked up, with always renewed amazement and envy, at Professor Ermanno’s wrinkled, keen face, as if transfigured at that moment, I looked at his eyes, which behind his glasses, I would have said were filled with tears. His voice was faint and chanting, with perfect pitch his Hebrew pronunciation, frequently doubling the consonants, and with the z, the s, and the h much more Tuscan than Ferranese, could be heard, filtered through the double distinction of culture and rank…

I looked at him. Below him, for the entire duration of the blessing, Alberto and Micòl never stopped exploring, they too, the gaps in their tent [the prayer-shawl]. And they smiled at me and winked at me, both curiously inviting: especially Micòl. (Ellipsis in original)

The narrator always wants to penetrate the closed-off space that is the life of the Finzi-Continis (the children don’t go to school, for example, and when they do have to appear for the end-of-year exams they arrive in a coach from the last century). The family, especially Micòl, seems to encourage him in doing so. But in the end he is just there on sufferance. Of course the ultimately irony is that whatever distinctions Jews make among themselves will be leveled by the terrorizing hate of National Socialism.

I’m drawn to your personal response to the work and how it resonated with you as an outsider, an immigrant and as someone who chose Judaism. The outsider element resonated with me too, and probably with many readers. I love how Bassani constantly literalizes this sense of exclusion, from the narrator seeing the Finzi-Contini children’s eyes peeking out from beneath the talit, to his initial inability to penetrate the Finzi-Contini estate during the beautiful young adolescent scene at the garden wall, to the lengthy, almost To the Lighthouse–like postponement of his entry onto the grounds then only much later into the house, and the remoteness of Micòl’s own room, which he is forced to conjure through imagination until he finally, too late, gets to see it for himself. Incidentally, that slow attainment of this “inner sanctum” appears to have as its countermeasure the slow encroachment of Fascism into the garden.

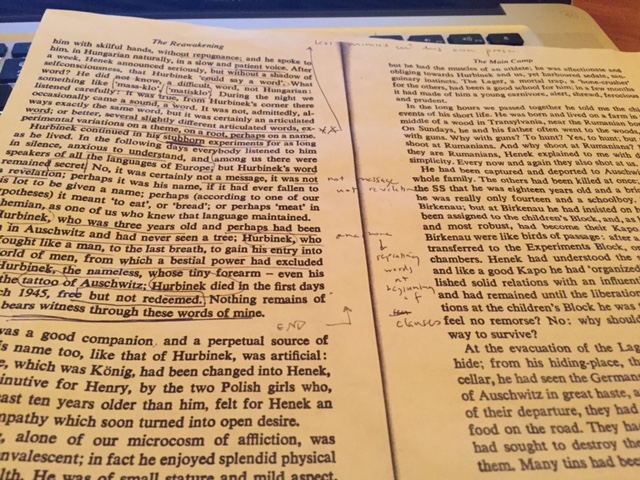

Of course another element that drew me into the novel is one you mention here: “At the same time, I wanted to escape that role by finding worlds or social situations that were just for me. Literature has of course been for me the most important and all encompassing of those worlds.” On the second read through, I was astounded at all the literature in this novel, which in addition to providing something of a crash course in late 19th century Italian poetry alludes to an astonishing variety of works, from Ariosto, to Stendhal (and the narrator, if anything, is a Stendalian figure), to Dumas, to Melville (I can’t recall whether Enrique Vila-Matas makes use of the “Bartleby” discussion in his Bartleby and Co., but if not, he missed a stellar example) and even possibly invents – in a curious passage – a Jewish poetess of 17th century Venice. A central literary figure is the renowned poet Giosuè Carducci, some letters of whom have come into the possession of Professor Ermanno, and around whom literary discussion sometimes revolves, especially arguments over Carducci’s nationalist sentiments and Republicanism (putting aside for a moment the characters’ religion, there is also in the novel an examination of their Italian-ness as relates to a glorified past now threatened by Fascism). Both the narrator and Micòl are by choice literature scholars, he in Bologna, she in Venice, he writing a dissertation on Enrico Panzzachi, a poet in Carducci’s vein, and she on Emily Dickinson. It’s telling that Micòl prefers “real novels” like The Three Musketeers to contemporary works like Cocteau’s Les Enfants terribles. It’s also telling that so little of what was transpiring in literature during the explosive literary decade of the 1930’s Italy appears in the novel. For all their obsession with literature, the narrator and Micòl seem little aware of what is being written around them, at least until the narrator argues with his father, towards the end, that “the only living literature” is contemporary literature. But again he names no names. Another thing I appreciate about Bassani is his avoidance of “literariness” by cleverly making his characters literary scholars themselves, thus allowing him to bring in discussion of all kinds of literature without having to shoehorn it awkwardly into the narrative. I can think of few novels with more literature in them – okay, maybe Roberto Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives.

Your dissection of the Jewish inter-relationships is fascinating. I assumed that the Finzi-Continis were Sephardic because of their obvious Spanish roots – the two uncles Herrera from Venice who are Spanish, their tendency to speak “Finzi-Continian” as the narrator calls it, a hybrid of Ferrarese and Tuscan Italian peppered with Spanish words. I don’t really subscribe to Tim Parks’ notion that Bassani “seems to relish” the idea of social division. Rather, I think this is part and parcel of a style that pushes things apart so as to make them more distinct, to gain some clarity. The remarkable Chapter IV of the first part, for instance, that portrays the inside of the synagogue, possesses the same kind of clarity with regard to the divisions among Ferrara’s Jews that Bassani applies to spaces and interiors, which he almost treats like staging. In addition, the use of such distinctions helps underscore Bassani’s emphasis on the democratizing, leveling force of death. Ironically, I think he’s actually more interested in commonality than in division, since from the beginning, with the visit to the Etruscan tombs in the Prologue, he stresses the universality of death and of remembrance. One could write an entire essay on the description of the Finzi-Contini tomb, with its weirdly international Greek, Egyptian and Roman features and garish conglomeration of materials that seem to come from all over.

II. Telephones

Telephones are really important in this book. Why? One idea is that telephones are a way to combine intimacy with distance. In another novel, characters might write letters to each other. But here they call each other—at least until they know each other well enough to simply drop in. (Well, the narrator drops in on the Finzi-Continis; they never come to his family’s apartment. That would be unthinkable.)

Telephones also a sign of wealth and privilege. Malnate, for example, a friend of Alberto’s, an engineer, a Gentile, a communist, and a rival to the narrator in a way he doesn’t foresee, doesn’t have one; the narrator has to wait outside his rooms when he wants to see him. Maybe it’s important that only the Jewish characters have telephones (though admittedly, there aren’t very many non-Jews in this book). I seem to recall reading someone—maybe it was the philosopher Jacques Derrida—who argued that the telephone is a particularly Jewish mode of communication because it concerns the voice: Derrida or whoever connected it to the Jewish prohibition on representations of God. In the Torah, God speaks (to Moses, to Abraham, etc), but is never seen, indeed, is not to be seen.

These speculations aren’t meant to suggest that the telephone is some kind of divine technology—yes, it facilitates important narrative events (Micòl invites the narrator to the inaugural tennis party over the phone; later, after Micòl decamps for university, Alberto invites him over for what become regular evenings with Malnate and the family) but it can also foil them (as when the narrator misses Micòl’s call to tell him she is leaving town).

So telephones can keep people apart as much as bring them together. But perhaps their most important function is as yet another way that otherwise inaccessible spaces can be entered. But always in mediated form. The telephone is a form of intimacy that is never too intimate: talking on the phone is different than talking to someone in person. Yet talking on the phone, especially to Micòl, is surprisingly intimate, or at least promises intimacy, because the Finzi-Continis have separate extensions in their rooms, so that when the narrator talks to Micòl she is typically in bed. And the narrator wants badly to know what that room looks like. Micòl refuses to tell him. The narrator always wants—and assumes—more intimacy with the Finzi-Continis than he is given.

What a great element to zero in on! I’d of course noticed the phones, but frankly hadn’t given them much thought other than as appurtenances of a wealthy family that wants to be up with the latest technology. I especially like your observation of them as “yet another way that otherwise inaccessible spaces can be entered.” This novel is chock full of inaccessible spaces, and/or of spaces that seem enclosed yet endless, Piranesian tunnels and abysses (I’m thinking in particular of the strange mounds near the city walls that had served as munitions caches, into one of which the narrator enters, at Micòl’s insistence, in order to hide his bicycle, but also of the configuration of the Finzi-Contini house, which like something in a dream the reader can never quite puzzle out – I couldn’t anyway). I found it almost painful how Micòl, who nearly always answers the phone, later lets others answer when she is avoiding the narrator – even that tenuous line to her cut off.

Material objects in general inhabit a strange space in this novel. Some – like the American elevator in the house or the ancient but still meticulously maintained carosse in the garage, appear to stretch the Finzi-Continis mystical aura temporally similar to how the vastness of the house and estate stretches it spatially.

III. The Narrator

For me, the narrator is the crux of this novel. The more I read, the more uncertain I became about him. I didn’t like or trust him. (So what could it mean that I identified so strongly with his desire to be accepted?) I couldn’t figure out what we’re supposed to make of him. He reminded me of the narrators of Kazuo Ishiguro’s novels—not showily or vertiginously unreliable (like Humbert Humbert in Lolita, say), but profoundly blind to himself, his emotions, and the world around him. Clueless, but with more menace.

Actually, by the end of the novel, I sensed we were supposed to think he’s been hard done by. But I couldn’t quite manage to sympathize with him, despite the one thing we learn about what happened to him during the war.

This piece of information comes at the end of an apparently heartwarming scene. The narrator has been kicked out of the public library (Jews are banned), and this is particularly humiliating because he’s completing a dissertation on 19th Century Italian literature. Once he learns the news, Professor Ermanno invites the narrator to use the family library. With its twenty thousand (!) volumes, the professor wryly notes, he should be able to make good progress. The narrator works in the library every morning, and he and the professor, whose study is next door, fall into a routine of checking in on each other:

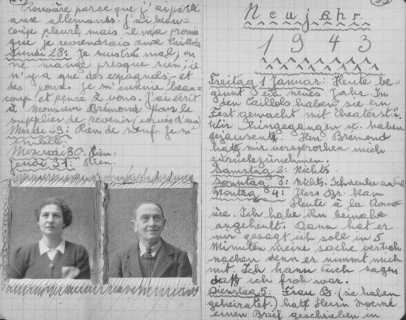

Through the door, when it was open, we even exchanged a few sentences: ‘What time is it?’ ‘How’s the work progressing?’ and so on. A few years later, during the spring of ’43, the words I was to exchange with the unknown man in the next cell, shouting them towards the ceiling, towards the air vent, would be of that sort: uttered like that, chiefly through the need of hearing one’s own voice, of feeling alive.

The narrator, we learn here, becomes a member of the Resistance (perhaps by being jailed for that reason he avoids being deported as a Jew—that almost happened to Primo Levi, for example). And his political commitment to fighting fascism should make us admire him. But I’m unconvinced. Even here the language is typically solipsistic. It’s probably more a commentary on the nature of imprisonment and the tactics the fascists used to crush their opposition than a criticism of his personality, but notice how the narrator’s prison “conversation” is really a monologue, practiced for selfish, though admittedly important, reasons, “the need of hearing one’s own voice.”

I can feel myself being unjust to the narrator here. But I wonder why this is the only reference to the narrator’s wartime experiences. Why not make more of it? After all, in the years after the war, everyone in Italy, it seemed, claimed to have been in the Resistance. It seems an obvious way to make us feel more strongly for the narrator. To me, it’s suggestive that Bassani downplays the option he’s given himself. Instead, he chooses to portray the narrator much more ambiguously.

Here’s a passage that stood out to me as particularly hard to parse. The narrator is celebrating Passover at home with his family. It’s 1939, and life for Italy’s Jews is getting ever more restricted. So what should be a joyous occasion is somber. The irony of celebrating the Israelites’ journey to freedom in a climate of anti-Semitism isn’t lost on anyone. But these societal concerns are less important—less irritating—to the narrator than his reluctance to be there. He chafes at his family; he wants to be with the Finzi-Contins. (Later, on Alberto’s invitation, he steals over to the Finzi-Contini’s Seder and notes that the same pastries he’d eaten with reluctance at home now taste delicious.)

Looking over the family members who have gathered to celebrate the holiday, the narrator sees faces that are “sad and pensive like the dead”:

I looked at my father and mother, both aged considerably in the last few months; I looked at Fanny [his sister], who was now fifteen, but, as if an occult fear had arrested her development, she seemed no more than twelve; one by one, around me, I looked at uncles and cousins, most of whom, a few years later, would be swallowed up by German crematory ovens: they didn’t imagine, no, surely not, that they would end in that way, but all the same, already, that evening, even if they seemed so insignificant to me, their poor faces surmounted by their little bourgeois hats or framed by their bourgeois permanents, even if I knew how dull-witted they were, how incapable of evaluating the real significance of the present or of reading into the future, they seemed to me already surrounded by the same aura of mysterious, statuary fatality that surrounds them now, in my memory…. Why didn’t I evade, at once, that desperate and grotesque assembly of ghosts, or at least stop my ears so as to hear no more talk of ‘discrimination’ and ‘patriotic merits’ and ‘certificates of services,’ of ‘blood quotients,’ and so on, not to hear the petty lamenting, the monotonous, gray futile threnody that family and kin were softly intoning around me?

What are we supposed to make of this? Even though the passage is divided between past and present, even though the responses at the time are coloured by the knowledge of how things would turn out, I don’t sense much compassion for the past.

It’s a trope of Holocaust literature to juxtapose past innocence to present knowledge, and some writers are famous for their ruthless and judgmental hindsight (Elie Wiesel in Night and Aharon Appelfeld in almost all of his works are classic examples). The narrator is similarly callous here: “The same aura of mysterious, statuary fatality that surrounds them now” isn’t much of a compliment. In fact, the whole logic here is hard to fathom. The narrator is saying: Even though they were so ignorant of what was to come, they nonetheless already had the same kind of fatality that they now have for me in my memory of them. It’s not that they were once vital, nor that their obliviousness has been ennobled or mitigated by the horrors that befell them. It’s that they haven’t even changed.

Is the idea then that the narrator’s prolepses—his flash forwards to future events—don’t make any difference? (Here’s an example from early in the book when as a boy he wanders around the walls of Finzi-Contini estate: “I stopped under a tree: one of those ancient trees… that a dozen years later, in the icy winter of Stalingrad, would be sacrificed to make firewood, but which in ’29 still held high.”)

I don’t know about you but I can’t warm to someone who listens to his frightened relatives and hears only “petty lamenting.” What does he want from them? Is it to be as blithely uninterested in the future as the Finzi-Continis? Maybe so: the scorn at the little bourgeois hats and hairdos sounds like something the Finzi-Continis might think, though would never say. Or, actually, it sounds like something they wouldn’t even concern them with. If anything, this is the narrator seeking—and failing—to ape what he thinks of as his betters.

It’s hard for me to excuse the narrator because of his youth: rather than callow he seems callous. Or somehow emotionally deadened, almost a bit autistic, though I’m uneasy at applying that kind of anachronistic diagnostic label. The novel often compares the narrator to Perotti, the Finzi-Continis’ servant, who disparages modernity even more than the family he has spent his life working for. You’d think that the suggestion that he is only a retainer to the family he admires so much—and possibly so pointlessly? I’m not sure what the novel wants us to think about them—would make us sympathetic to him. But I don’t think it does.

Not even the final “revelation” of why Micòl has spurned his often clumsy, even violent advances doesn’t change my feelings—SPOILER ALERT: he thinks Micòl has been having an affair with her brother’s friend Malnate—especially because I don’t see any evidence that this outcome is anything other than a self-serving construction on the part of the narrator.

Please tell me what you make of the narrator. Why is it that he doesn’t seem to have any present-day (that is, post-war) existence? He’s just a ghost in that opening section, as if he lives only to tell this story of the past.

I’m a little surprised by the degree of your negative reaction to the narrator, as I found him more sympathetic than not. True, he displays a great deal of immaturity – it’s not at all difficult to understand Micòl’s rejection of his groveling, possessive behavior – but at the same time he seems to grow in ways that the other characters do not. Micòl seems to retreat further and further into her Finzi-Continism. Alberto fades almost literally, recusing himself from the intense political discussions the narrator and Malnate engage in together and then, of course, slipping into terminal illness. And Malnate adheres to a fairly strict and pat Communist party line (despite his unexpected appreciation of poetry as revealed near the end; one other minor reason to read Garden is that one gets a rare English translation of Milanese poet Carlo Porta!). The narrator, despite having changed his dissertation interest from Italian Renaissance painting to Panzacchi, in the end advocates for living, contemporary literature, pushes back against those who seem to be inhabiting the past and lacking in foresight as regards the dangers Fascism poses for the future. And yet I agree that it’s unclear how much of the narrator’s “awareness” of that danger is supplied through his backwards glance. Still, if one thinks of Garden as a Holocaust novel, then the narrator plays the essential role of witness, one for whom the question of reliability is almost beside the point. It’s not as though the Finzi-Continis’ fate or the ravages of the Racial Laws are in question. Bassani’s own father disappeared into the camps, and it’s significant – almost irresistible to a writer, I would think, a Jewish writer from Ferrara no less – that of the 183 Ferrarese Jews rounded up and deported to Germany, only one survived. The narrator is obviously not that one, but he plays a role one could imagine that person playing, of having alone survived to tell the tale.

While I also thought the Passover supper scene complicated and puzzling, the narrator’s attitude made some sense to me given the dark constellation of tensions under which he had fallen: the rupture with Micòl; the somber, empty celebration given the dinner talk of increasing restrictions; the abeyance in which he finds himself after completing his dissertation yet – partly because of those restrictions – having no clear option for his future; and perhaps above all his complicated attraction to the Finzi-Continis, who have appeared from the beginning to represent for him wealth, culture, education, beauty even, and perhaps most of all what he refers to early on – and I can’t find the quotation – to their isolation, an aloofness, an outsider quality, that he himself feels almost as a privilege. Though at this point of the novel, the Passover dinner, the narrator is in his mid-twenties, I almost see him as a rebellious teen just itching to get out of the house and go where he’s understood – or perhaps more accurately where he’s among people with whom he aspires to belong.

There’s another element to this behavior hinted at not very obliquely in the remarkable father/son scene near the end of the novel and given a significant clue in light of that scene’s mention of the incident with “Dr. Fadeghi,” which must strike some readers as puzzling since it’s never explained and seems gratuitous. This is a reference to Bassani’s The Gold-Rimmed Spectacles, and thus to the narrator’s possible, even probable homosexuality. His father is on the cusp of suggesting as much but can’t say it. Suddenly the narrator’s timid, aloof, unconsummated attraction to Micòl makes sense. I wondered about this too in relation to the prologue, where he’s traveling with “friends” from Rome as a lone man in a car with a family. There’s a second car of friends too, but who is in it? Why is the narrator stuck with the family? What’s his relation to them? They’re likely not Jewish, as we suspect from the father, laughing, telling his the daughter to ask the man in the back seat to answer a question she has about the Jews. I’m not sure that helps with your questions.

IV The Translation

William Weaver’s translation seemed to me excellent, but I don’t have any Italian, and I’m eager to hear your thoughts. I’m especially curious to hear how other translators have dealt with the text’s references to Hebrew and Yiddish, in particular, and Jewish custom and tradition in general.

I can only address the translations to the extent of my ability amateur opining, so I’ll only say that they struck me as quite different. McKendrick’s seems more precise, formal and elegant, which I suspect might be the right fit for Bassani. But Weaver’s seems warmer, more casual, closer to the blood that pulses through Bassani’s young characters. In the end, I could toss a coin and be content either way it landed, though I might hope slightly that it would land with McKendrick face-up. I took a look at the Hebrew/Yiddish language references in both translations, and while neither translator resorts to awkward English equivalents, McKendrick uses quite a bit more of the Hebrew/Yiddish terminology than does Weaver. I certainly get the sense that McKendrick is more careful than Weaver.

To summarize my main points: I’m really drawn to a novel narrated by a character I’m skeptical, even, it’s not too much to say, repulsed by. What’s especially weird about that is that I really sympathize with the narrator’s desire to be accepted by a family and a social world not his own. Maybe what I can’t take is the rejection of his background entailed by what at its best is not mere social climbing but rather a way to express who he most fully wants to be.

I did not get a sense of the narrator engaging in “social climbing” so much as wanting to escape from a relatively limiting environment – and in this regard the novel did have personal resonance, since I could not wait, as an adolescent, to escape the confines of a bourgeois home and find others interested in art, literature, travel, a wider view. So we have different takes – and therein lies the value of doing this sort of collaborative reading. I’d like to continue the discussion, and may send you a few meditations of my own about Bassani’s novel and ask for your responses. I’m eager now to go see what others have written.