Plenty busy chez EMJ last month. Two weeks studying Holocaust photographs in a faculty seminar (inspiring, transformative, draining). One week teaching an online class (enjoyable, tiring). One week doing absolutely nothing but reading and chilling (bliss). And one week trying to catch up on all the things (I know this makes for five weeks, not sure what to tell you).

Although much of my reading concerned the history of atrocity photographs, I made time for a number of other things. I got into a good rhythm: get up early, read something demanding for an hour or so; crash in the afternoon and evening, read fluff. Spent much of the month in St Louis: nice to be somewhere where you can sit outside in the summer. Also: Ted Drewes FTW!

Richard Wright, Black Boy (American Hunger) (1945/1991)

In the first pages of his autobiography, Wright, a bored four-year-old, almost burns his grandmother’s house down, and the rest of the book is seldom less incendiary. Amazing that Wright survived not just that errant moment but his childhood at all. So much abuse, contempt, despair. Wright wanted to call the book American Hunger, a resonant title that suggests not just the hunger that African Americans have felt to belong to their country but also the hunger with which America has devoured them. Most of all, though, the title is literal: Wright was seriously undernourished much of his life, even into adulthood. (He was turned down for a good job with the post office because he didn’t weight enough.) In one indelible scene, Wright, who has been deposited in an orphanage because his mother temporarily can’t take care of him, is dizzy with hunger. He and the other children were fed only twice a day—before bed they received a thin slice of bread with a smear of molasses—but that didn’t save them from having to work. For example, they had to “mow” the orphanage’s grounds: a herd of children on their hands and knees, pulling the grass out in clumps, often too lightheaded to make any headway.

Wright changed the title to Black Boy after the Book of the Month club, which had selected the title—as it had done some years before with Native Son—declined to publish the manuscript’s second half, which describes Wright’s experiences after escaping the South for Chicago, specifically his involvement with the communist party. (I gather the party pressured the BMOC to make the changes, which suggests an America so different from the one we live in I don’t even know what to say.) I sort of agree that the parts about Wright’s childhood and early adulthood in Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee are more compelling. They’re certainly more reducible to a narrative of suffering that makes sense to (white) readers. (And ending with the train ride to Chicago implies an overcoming that the rest of the book belies.) But I found the cruel political machinations described in the second half engrossing—excommunication, quasi-Stalinist show trials, oof. Wright believes there is something essential to communism that cannot be quashed by its instantiation, whether in the Soviet Union or south side Chicago. It emphasized self-sacrifice in a way his own life had prepared him to understand.

What stands out to me about Black Boy is its almost complete lack of joy. Wright’s life was hard, his upbringing mean, in both senses of the world, his horizons cramped by racism and the strict religion of his family. There’s nothing here to compare, for example, to the meaningful pleasures described in Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s Colored People. (Admittedly, Gates was of a different class and writing about the 1950s not the 20s and 30s.) The funniest scene concerns his job as a janitor at a Chicago hospital. Not that this was a good time. Together with three other men, all Black, Wright worked without thanks and almost without recompense: his description of mopping stairs that people immediately muck up, offering what they think is an amusing quip about how work is never done or, as is more often the case, not even seeing him at all will make your blood boil. The basement of the hospital contained a lab where white scientists performed experiments on animals (afflicting mice with diabetes and other horrors). One day, two of the janitors, who hate each other, get into a fight that turns into a brawl—the cages are knocked to the floor, and most of the animals escape. With only minutes to go before the scientists are due back from lunch, Wright and the others chase the animals, tossing the animals into cages willy-nilly. Who knows, Wright wryly speculates, what medical advances were made that day. Yet this scene, which in another writer’s hands could be laugh out loud funny, is tense, terrifying. The consequences of discovery for Wright and the others are simply too great.

Poverty is corrosive, yet Wright’s escape carries with it regret, loss, sorrow, and rage. In a riff on Du Bois’s idea of double consciousness, Wright describes his literary self-education—he used the library card of a sympathetic white co-worker to check out books—as a mixed blessing:

In buoying me up, reading also cast me down, made me see what was possible, what I had missed. My tension returned, new, terrible, bitter, surging, almost too great to be contained. I no longer felt that the world about me was hostile, killing; I knew it. A million times I asked myself what I could do to save myself, and there were no answers. I seemed forever condemned, ringed by walls.

Communist party meddling or no, I can see why white publishers were wary of the book’s refusal of uplift. To me, the characteristic Wright note here is that added “killing”—Wright suffers plenty of physical violence, but his mental anguish is even worse.

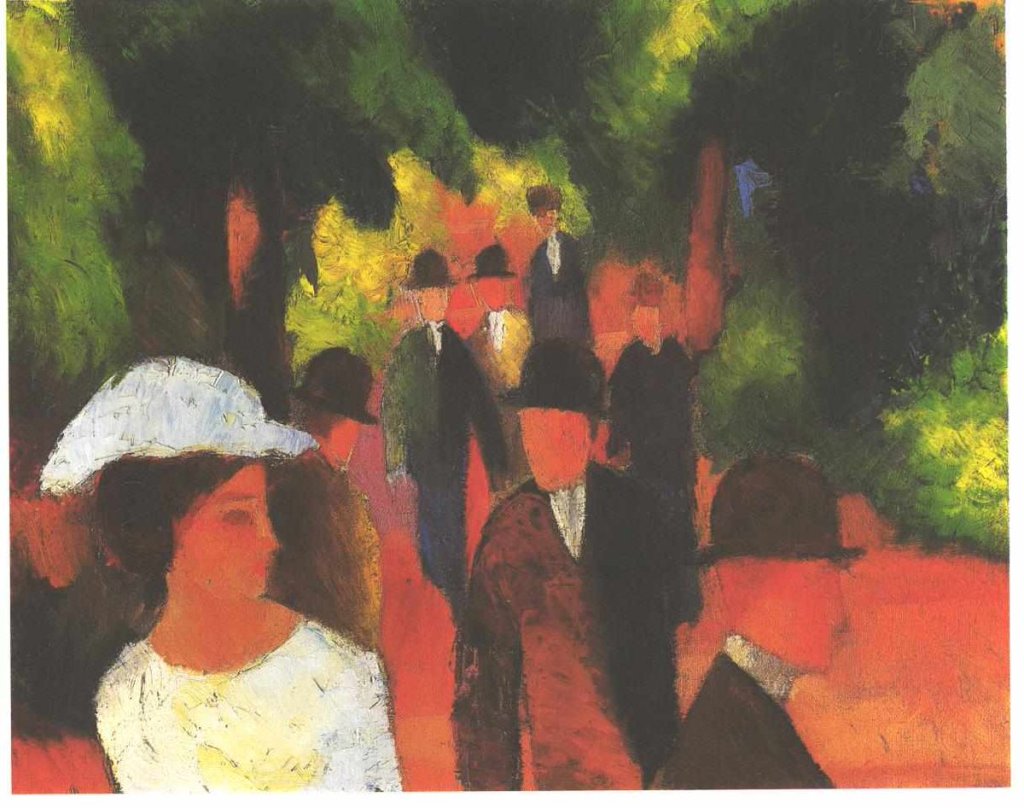

Audrey Magee, The Colony (2022)

In the summer of 1979, two men arrive on an island off the west coast of Ireland. One, an English painter, is running away from a failing marriage and doubts about his artistic relevance, and in search of fabled light. The other, a French academic, is returning to complete the field work for his anthropological and linguistic dissertation on Gaelic. The story of how their competing presences—expressed in dinner-table arguments about whether English and the modernity it is the vehicle for is ruinous—shape the lives of the family that has rented them their rooms is interspersed by short chapters that detail, in neutral language, killings perpetrated by Protestant and Catholic paramilitaries back on the mainland.

I’m a sucker for windswept northern landscapes, and any story in which the making of tea is a repeated and central element will always be meat and drink to me. But I liked Colony for other reasons too. It’s a think-y book that never feels plodding. Magee argues that the depredations of colonialism take many forms—the fantasy of linguistic purity as harmful as airy invocations of progress. The latter, so Magee, always require someone be exploited. She tackles a lot here, and I wasn’t always convinced by the juggling act (a backstory about the Frenchman’s childhood as the son of a pied noir needed to be better integrated), but I appreciated her ambition.

Thanks to John Self for turning me on to this one.

Sylvia Townsend Warner, Lolly Willowes , or The Loving Huntsman (1926)

An unmarried woman in England between the wars becomes a witch. Or decides to live as the witch she has always been. Frances, Rebecca, and I talk about this on Episode 5 of One Bright Book—I loved it less than they did, was not quite swept away with it as I’d hoped, but I definitely recommend. Warner is perhaps a little chilly for me, and I do wonder about the implications of emphasizing (only?) a magical solution to a political problem—what will it take for women to be left alone? Prefer Comyns’s The Vet’s Daughter, for a not dissimilar English magic-realist admixture.

Check out these pieces by Rebecca and Rohan for more thoughts on what Warner is up to.

Garry Disher, The Way It Is Now (2021)

Diverting crime novel with good surfing scenes. The son of a cop, himself recently a cop—he fell in love with a witness and has been suspended—has never stopped trying to find out what happened to his mother, who disappeared twenty years ago. New evidence comes to light, and things look even worse than ever for his father, who has always maintained his innocence.

Not the best Disher I’ve read, but he’s so damn competent, not sure he can write a bad book.

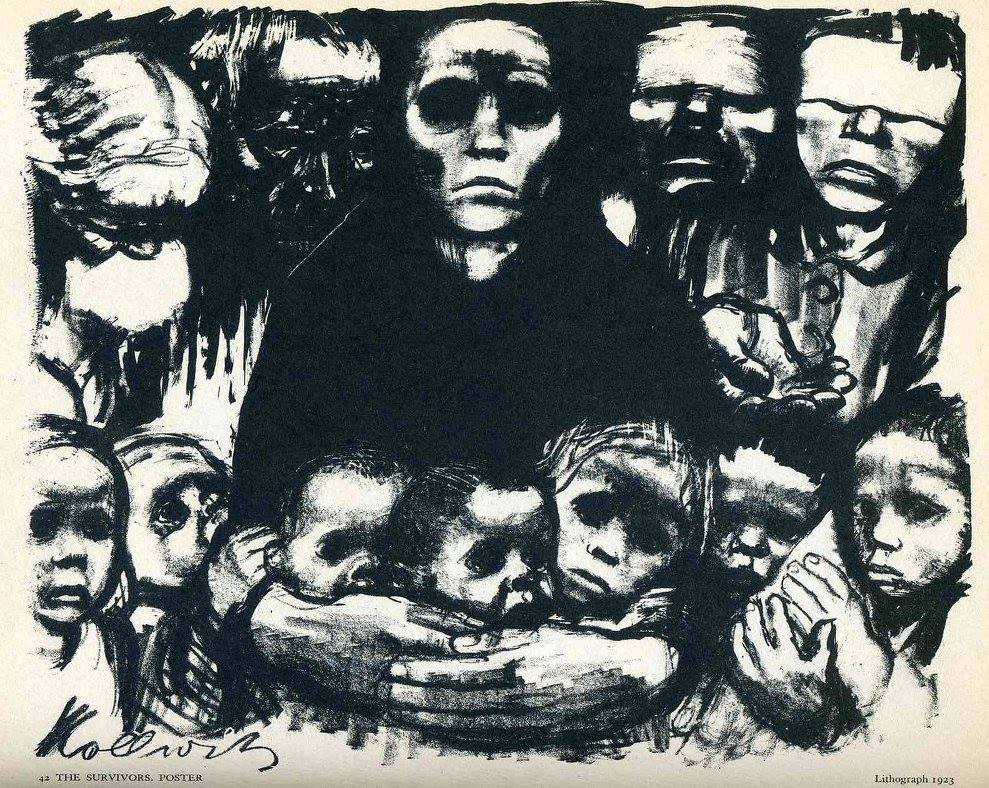

Charlotte Schallié, Ed. But I Live: Three Stories of Child Survivors of the Holocaust (2022)

[Created by Miriam Libicki and David Schaffer; Gilad Seliktar and Nico & Rolf Kamp; Barbara Yelin and Emmie Arbel]

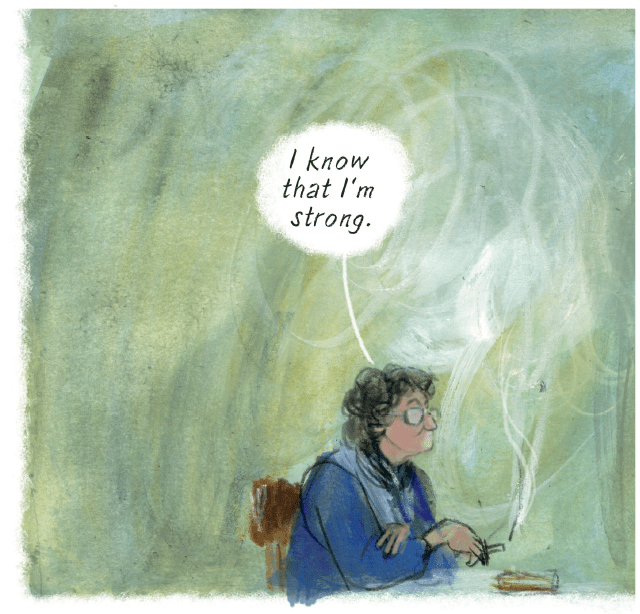

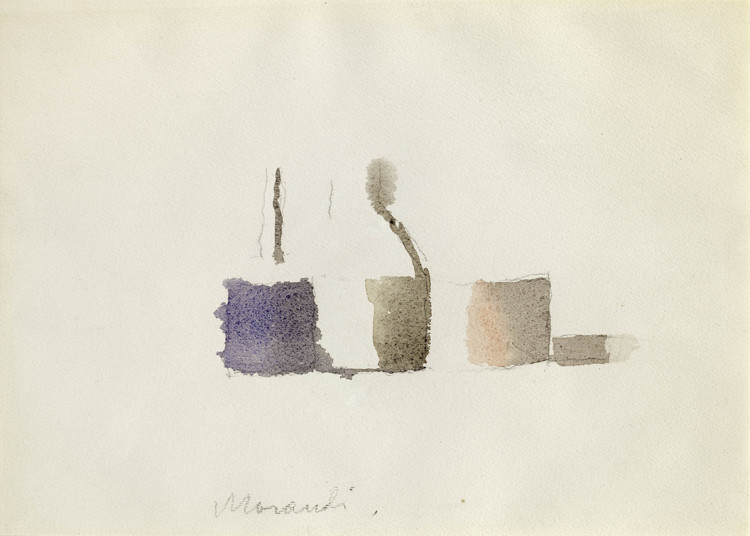

Beautiful & moving collaboration between child Holocaust survivors and graphic novelists, with impressive critical and historical appendices. Libicki fittingly illustrates Schaffer’s story of hiding in the forests of Transnistria—what horrible things happened in that benighted territory—in the style of an edition of the Grimms. The minimalist Seliktar (he reminds me of Manuele Fior) uses a palette of purple/blue + yellow/brown and delicate shading to accompany the story of the Kamp brothers’ time in hiding (in thirteen different lodgings, including a chicken coop) in Holland. Yelin, whose marvelous Irmina I raved about last year, tells the bleak story of Emmie Arbel’s terrifying experiences as a five-year-old in Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen, where she had to watch her mother starve to death as a result of dividing her meager rations among her children (all three survived, miraculously). After a long recuperation in Sweden, the siblings immigrated to Israel, where Emmie struggled again, especially in the kibbutz system of education/neglect. All three artists include their exchanges with their subjects in their comics, but Yelin’s self-reflection is the most extensive. In the process she shows how thoroughly Arbel was damaged by her experiences, to the point of passing her trauma on to her children.

The project is a triumph. Schallié deserves credit for bringing together survivors, artists, and scholars—and for securing the funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Reseach Council of Canada that supported the collaborative project of which this book must be the centerpiece. In addition to the three comics, there’s a further comic describing the artists’ cooperation, a brief statement from each of the survivors themselves, and lucid, informative short essays expanding on the context of each survivor’s experiences by scholars. I especially appreciated Alexander Korb’s piece on the Holocaust in Transnistria.

Did I mention that But I Live is gorgeously produced and printed, too? A must read if you have any interest in the topic.

Kim Stanley Robinson, Aurora (2015)

Excellent novel about a spaceship—outfitted with twenty-four complete biomes and about two thousand people—on a mission to an earth-like moon in the Tau Ceti system. Despite having been slingshotted from Saturn at who knows how much the speed of light (Robinson does know, and goes into detail, but I can’t follow him when he gets all engineer-y), the trip takes 160 years, and so the people on board as the ship approaches Aurora are several generations removed from the ones who set off.

Two women are at the center of the novel—Devi, the ship’s de-facto chief engineer, and Freya, her daughter. (Robinson’s great theme is the power of the engineering mindset, its ingenuity and improvisation, when tied to a politics of care.) The other protagonist is Ship itself, whose AI comes to self-consciousness through long conversations with Devi, and her command that Ship write a narrative of the voyage. (The meditations of the relation of narrative to consciousness are the least successful part of the book.)

The travelers begin the process of terraforming the moon, but it turns out that it is inhabited, at minimum, by a prion that is fatal to humans. The crew faces a decision—turn their efforts to a nearby moon in the hope that it’s more hospitable, or return to earth, something Ship was not designed for. The dilemma almost leads to civil war—only Ship’s intervention as The Rule of Law permits a non-violent resolution of the situation. Most decide to return, but a large minority opt for the unknown. We never learn what happens to them. Probably nothing good, but Robinson leaves their experience as a tantalizing possibility and a symbol for all that can’t be known.

The voyage home is perilous for many reasons—the biomes are failing, the crew is starving, authorities on earth respond too late to slow Ship down, necessitating a dangerous twelve-year journey through the solar system where, theoretically, the gravitational forces of the planets create will enough drag for the crew to splash down.

Aurora is moving, suspenseful, and thought-provoking. As a book about politics and the insatiable human demand to make and do—which, Robinson suggests, ought to be confined to our own planet—it made a fascinating and unexpected pairing with the other book I was reading at the same time, namely…

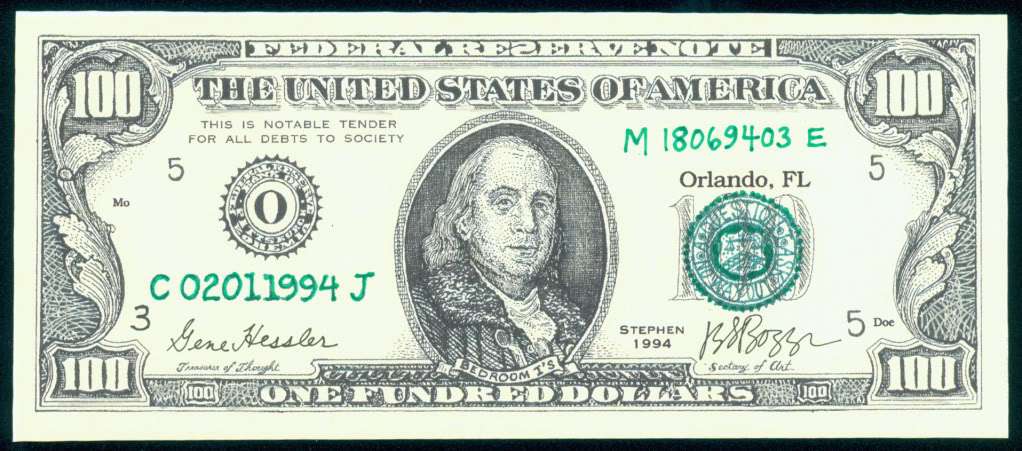

Guido Morselli, The Communist (1976) Trans. Frederika Randall (2017)

Published after his death, like all his novels, Morselli’s The Communist was written in 1964 – 65. It’s set a half-decade earlier, at a time when the Communist party in Italy boasted the third-largest membership in the world, after only the USSR and China. Its success stemmed from its active role in the resistance to fascism, and translated, in the first decade or so after the war, into parliamentary success, although its members were divided about participating in the act of governing. Would that not legitimate the system they wished to overthrow? The Communist is about one of these new parliamentarians, Walter Ferranini, a man whose life has been devoted to the left, even if the left has not been devoted to him. The son of an anarchist railwayman, Ferranini served in Spain before finding his way to the US, where, despite himself, in a manner that seems to emulate the bourgeois striving he abhors, he marries the daughter of his boss and allows himself to dream of the family’s place in the country. But when his wife turns reactionary, throwing herself into a nativist movement, and with the war over, he returns to Italy and throws himself into labour activism in Reggio Emilia.

It is on the basis of his success in these practical matters, and his genuine commitment to improving the lives of the workers, that Ferranini is elected a deputy in the national parliament. Although he lives to serve, he is unhappy: his dream of introducing a bill to expand worker safety is met with hostility and derision by members of his own party; he feels increasingly unable to discipline colleagues who call out hypocrisy among party leaders; he falls afoul of party orthodoxy when he writes an article for a journal headed by Alberto Moravia; and his affair with married but separated single-mother is used by the party as an excuse to discipline him. No wonder his health is so bad. And then comes a telegram from the US—Nancy, his wife (they never divorced), is seriously ill. He gets a flight, arriving in Philadelphia in an epic snowstorm that incites the novel’s satisfying denouement.

Ferranini is a sad, lonely, and, yes, noble character (he’d despise that description, though, and the book sympathizes but never romanticizes him). Morselli writes with deep interest, if not tenderness, but entirely without sarcasm or satire about the tendency of belief systems and institutional structures to obscure the insights that sparked them. Ferranini’s article, the one that gets him in trouble with the party bosses, is about the inescapable reality of toil. Contra Marx, he argues, not even achieved socialism will be able to undo this reality. (Hannah Arendt would approve!) Workers don’t feel alienated; they feel tired. As he says:

Admit it, there are things that technology cannot achieve. There is a law that can’t be breached, a physical and biological law that says life can’t arise and survive without sweat and struggle. And especially not without struggling against the environment, the surrounding material reality, and labor is part of this.

The Communist, one of the best books I’ve read this year, so thoughtful and, oh I don’t know, solid, though never turgid, presents activism and labor organizing as real labor, less exhausting and dangerous than work in a mine or factory or agricultural cooperative, but exhausting and dangerous nonetheless. Most of the people who do that work are not dedicated to it—some are outright cynics, former fascists who became fervent communists when they saw which way the wind was blowing; Ferranini is exceptional. Morselli allows us to believe in his integrity even as he also shows us that the system the man works within ultimately holds him in contempt. It would be easy to conclude that Ferranini is a dupe. Morselli refuses that temptation. Neither does he make the man a true believer. He is something rarer: someone who does the work, because the work is good, if, as it is supposed to, it eases our exhaustion.

Nora inspired me to read this, and am I ever glad. Grateful too to the late Frederika Randall for bringing this book into such lovely English.

K. C. Constantine, The Man Who Liked to Look at Himself (1973)

The second Mario Balzic mystery is a step-down from the first—less interesting, plot-wise, and dismayingly retrograde in its use of slurs, to say nothing of its portrayal of queerness—but Constantine is good with the snappy dialogue and Balzic is shaping up to be a great character. I’ll give the series a little more rope.

Sally Rooney, Beautiful World, Where are You (2021)

Loved it! Still think Conversations with Friends is the one to beat, but I’m appreciating the maturing of Rooney’s characters as she herself ages, and I just think she gets “the whole meeting smart friends when you are young and then sticking with them for years even as your lives change” thing. Also, a great writer of sex.

Setting down to write what became The Rainbow, Lawrence said in a letter that he was going to follow the master, Eliot, and do what she did: take two couples and set them against each other. Rooney does the same here. Of her four protagonists, the non-intellectual Felix interested me the most, there’s a Mephistophelean quality there that is directed outward rather than inward (most of the bad things in her other books have involved self-harm), though I think Rooney took the easy way out at the end and tamed him, made him just curmudgeonly when he might have been something else.

This was great on audio, by the way, Rooney’s Irishness much more evident.

Kotaro Isaka, Bullet Train (2010) Trans. Sam Malissa (2021)

Extravagant thriller with more plot twists than any five books need, let alone one. The premise is cool—a bunch of assassins and other thugs are stuck on a bullet train from Tokyo to Morioka. Their various errands center on a suitcase full of money and the son of a mobster who winds up dead a few pages into the book. At first I was into it, the reversals were clever and the characters intriguing. But then the book spoils the fun by taking take itself seriously—there’s a running question of why people think it’s ok to kill other people, what makes for evil in the world, etc. Because I don’t respect myself, I finished it, all 432 pages.

There you have it, folks. Began with a bang, ended with a whimper, but, really, this was the most solid reading month in ages. Almost everything was good, but special shout-outs to the Wright, Robinson, and Morselli. Three best-of-the-year candidates right there. Marginal consolation in a time of the rampaging new American illiberalism. I hope you all are well and not too disheartened.