October 2022 was months ago, I just remember we headed into the heart of semester, and it was still too hot a lot of the time, except at the end. I had a lot going on, but I managed to read quite a lot somehow. (A few of these had been on the go for a long time, though.) This is the last of these 2022 months I’ll complete. I’m missing July and August, which were good reading months, but some of those titles will appear on my Year in Review piece, which I’ll finally turn to now…

Larry McMurtry, Streets of Laredo (1993)

After finishing Lonesome Dove a couple of years ago, I asked Twitter if the book McMurtry later wrote with many of the same characters were as purely enjoyable. The answer was a resounding no, with a few even warning me not to read them, as their joylessness would retrospectively taint my feelings about LD. That was a flag to a bull, of course, and a friend and I decided to start with the book McMurtry wrote as a sequel.

It is, predictably, grimmer and more valedictory. The mythic West, already shown to be faded and false at the end of Dove, is really no more in The Streets of Laredo. And any book without Gus McCrae is going to be more a downer than one with him in it. The former heroes are old and failing, the new young’uns are clueless or vicious. But characters who didn’t shine in that earlier world get their due here: who knew that Pea Eye would grow to have so much self-knowledge? And women are important in this book, Lorena in particular is magnificent. The primary indigenous character, though, well, less two-dimensional than in Dove, and intended, I suspect, as a tribute, is an embarrassment, there’s no way around it.

Laredo is a violent book, much more so than Dove, verging even at times on Blood Meridian levels. It’s not a nihilistic book, though, unlike McCarthy’s, and indeed in the end a peaceable, fallible one. I loved it, and didn’t regret reading it for a second, and will give the two prequels a try soon enough.

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim, The Waiting (2021) Trans. Janet Hong (2021)

Every year on Yom Kippur, in the hours between morning services and ne’ila, when I’m too hungry and headache-y to sleep, I pick up a book that has nothing to do with work. Bonus points if it’s not too taxing, but also on the somber side. The Waiting fit the bill: a beautifully drawn and told comic about a family separated during the Korean War, and the aftermath of that trauma. Every year hundreds of people in South Korea—all of them now old, most frail—apply to meet relatives who found themselves in what became North Korea after the freezing of hostilities in the 1950s. The exchange is tightly controlled by both sides; only a handful who apply are chosen. The meetings happen at special facilities on the border: people who haven’t seen loved ones in decades are given a few hours together, an opportunity that can be almost as painful as not being selected. I knew nothing of this, and would, I’m sure, have been overwhelmed by sadness even without the somberness of the day.

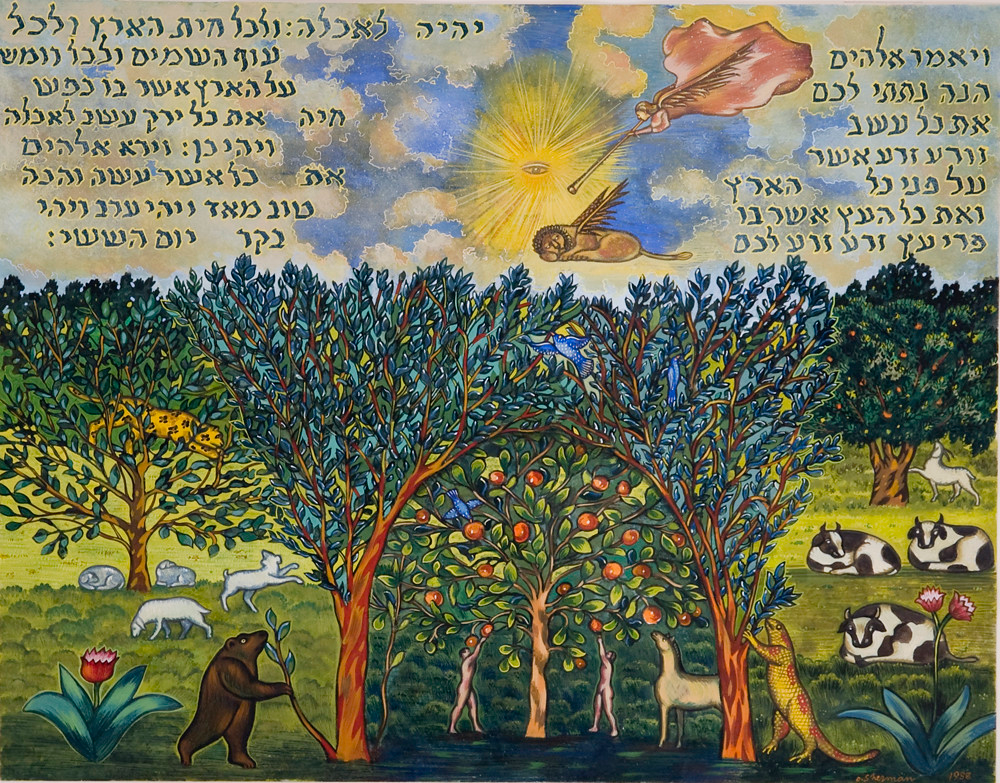

Michael Frank, One Hundred Saturdays: Stella Levi and the Search for a Lost World (2022) Illus. Maira Kalman

A wonderful book, that rare thing, a Holocaust text that is as much about the world that was destroyed as the events of the destruction. In Stella Levi’s case that world was fragile to begin with, though absolutely vibrant. Only two thousand Jews lived on the island of Rhodes in 1939, and, since the island had been controlled by Italy since the end of the last war, life for the community did not change much until the Germans took over in September 1943. (Which isn’t to say the Italians leveled no strictures on the Jewish population: in 1938, for example, Jews were expelled from the universities.) Almost the entire population, save a handful who could claim Turkish citizenship, were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1944. Only 150 returned. And most of those were unwilling to live in Rhodes again: a community that had flourished for over 2000 years, and in its final, Sephardic incarnation since the 16th century, was gone.

Stella Levi, born in 1923 as the youngest of seven children to a merchant family, is one of the last people alive who experienced life in the Juderia, the Jewish quarter of Rhodes, a place where people knew their Greek and Turkish neighbours, did business with them, lived in harmony, but mostly ignored them; it was inward-focused life, and, until the arrival of the Italians, resistant to modernity.

Michael Frank met Levi one evening in 2015 when, arriving late for a talk at the Italian cultural center in New York, he dropped into the only available seat. The elegant woman next to him asked him where he was coming from in such a rush. His weekly French lesson, Frank replied, to which Levi replied, Would you like to know how French saved my life?

The short answer was that in Auschwitz, where she and her entire family and community had been deported, no one had ever met Judaeo-Spanish speakers. They were met with consternation, from the perpetrators and other victims alike. Did she know Yiddish? Polish? German? No, no, no. French? Yes, French she knew—which meant that she was placed with women from France and Belgium, women who knew enough of those other languages to help themselves, and by extension, Levi, get by.

The full answer took longer to uncover. Over six years, Frank would arrive with pastries at Levi’s apartment most Saturday mornings and listen, with occasional questions, as Levi felt her way into telling her life story. Her many reservations about doing so are at the heart of the book: Levi, who had kept these experiences to herself, rightly feared being reduced to an Auschwitz survivor. In Frank she found the right teller: careful, receptive, deferential, but no pushover. Their pas-de-deux is a lovely love story. Levi herself, you might already have guessed, is a remarkable person, with plenty of wisdom but no life lessons, if you know what I mean.

As if this book weren’t awesome enough, it also has illustrations by the great Maira Kalman. They are of course stunning. I read this book from the library, and I may need to get my own copy, and I never say that. An end-of-year title, for sure.

Jessica Au, Cold Enough for Snow (2022)

Disquieting, beautiful novella about an Australian woman who takes her mother on a trip to Japan. They walk around Tokyo, have dinner, visit a bookshop, attend an art exhibition. It all sounds nice enough, and the narrator’s attentiveness makes the journey vivid but not fetishistic. Yet the more I read, the more uneasy I became. In the guise of being helpful, the narrator in fact bullies her mother, insists upon having things her own way, force-marches the old woman through a series of sites and visits she has no particular interest in. Riley’s My Phantoms is getting all the love, but in the Bad-Daughter sweepstakes, Au takes the crown. Her control is impressive and I’m excited for her next book. [Attention, spoiler alert! I know some readers say the mother has in fact already died, that the narrator is accompanying a ghost, and I see where they’re coming from. I suppose I just don’t want this reading to be true: it seems less interesting to me.]

Namwali Serpell, Stranger Faces (2020)

I read the first pages of Serpell’s book-length essay online last spring and impulsively ordered it for my composition class this fall, since I planned to do a unit on writing about photographs. Those pages were so good! Serpell brilliantly close-reads the sentence “Look at me”; I imagined working through these pages with my class, using it to confirm the practice we’d already have done in learning to paying attention. I couldn’t wait to read the rest of the book, which was bound to be just as good.

Well.

It’s fine. A little labored. I appreciate Serpell’s insistence that we value so-called strange or other faces—those faces, the ones we are inclined to turn away from, have more to tell us about what it means to be human than any others. She’s good on the various writers and filmmakers she writes about (Joseph Merrick, Hannah Crafts, Alfred Hitchcock, and Werner Herzog), though too inclined to use puns and riffs structure her analyses. She’s most interesting in her final chapter on non-artistic practices, especially emojis and gifs (which prompted a class discussion in which I learned that only olds use gifs). Stranger Faces is like one of those restaurants where only the appetizers and desserts are any good.

Less good, in fact, not at all good, was the class I read it with. Probably the most challenging group I’ve ever taught. The book, I realized, wasn’t really pitched right for the class (that’s on me): not enough about photography per se, and too difficult, despite its reasonably straightforward prose, for the group. Pretty sure some of them didn’t read it, or read it quickly (that’s on them).

In a different context I might feel differently about the book, but I still think I’d find it underwhelming.

Andrea Barrett, The Air We Breathe (2007)

Old-fashioned novel about a tuberculosis sanitarium in the Adirondacks during WWI. Wealthy patients live in what are called cure cottages run by private families. Poor patients, mostly recent immigrants from Europe, are sent as wards of the state to a public facility. Written mostly in the months after 9/11 (Barrett apparently started a fellowship at the NYPL on September 10th), the novel compares the war against tuberculosis with the patriotic fever whipped up as America prepared to enter the war, concerns that became newly relevant as she sat down to write. In each case, a “pure,” “healthy” body politic defined itself by ejecting an “impure” “unhealthy” other.

A wealthy man, manager of a munition factory, decides he will bring culture to the sanitarium’s residents by starting a weekly conversation group. What starts as a way for him to dilate on his passion for paleontology becomes something more inspiring—and dangerous. As the patients, many of whom have skills and knowledge unsuspected by the officials and orderlies who see them as unwashed immigrants, share the most important parts of themselves, larger passions intrude. All of this occurs against a backdrop of wartime jingoism, industrial production, and labour unrest. And of course, people fall in (almost always unrequited) love. The rich man loves a nurse who loves a patient who loves another nurse who is taken under the wing of a female scientist, the facility’s x-ray technician. The political and emotional tensions amp up; terrible things happen.

I loved this book. Sitting outside on the back steps in the mild weather on my Fall Break when I should have been doing other things, I delighted in its novelistic sweep, its warmth, its intelligence, and its deft use of narrative voice (Barrett’s choice to swerve between close third person and the first-person plural in which the patients speak as one impresses). I started by saying this is an old-fashioned book, but like a lot of old-fashioned books it offers a lot of surprises.

My first Barrett, but not my last.

Kate Zambreno, To Write as if Already Dead (2021)

Rebecca selected this for the October episode of One Bright Book. Not something I would have read otherwise; that’s one of the pleasures of the podcast. To Write as if Already Dead is Zambreno’s effort to write about Hervé Guibert’s To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, a roman-à-clef about the narrator’s AIDS diagnosis and friendship with Michel Foucault. My halfhearted plan to read the Guibert first came to naught, but I didn’t sense (and my cohosts confirmed) that having done so would have made much difference. Zambreno tells us enough of what we need to know about the writer and his most famous work, the one she circles around in her own book. She’s supposed to be writing an appreciation of Friend, but she struggles with the task, asking herself why she isn’t writing about David Wojnarowicz, whom she actually likes more than Guibert, but the bulk of the book, fortunately, isn’t about her inability to write her book. Instead it’s composed in two sections: one a “novella” about a first-person narrator who is surely Zambreno and the complicated, envious relationship she had with another female writer back in the days when blogging was a going concern (and not just something a few us old heads persist in doing), the other a set of notes written in response to (usually in the widest sense of the term) Guibert’s text. I could discern no tonal or stylistic differences between the two parts—which maybe is the point?—and in general rubbed against the book at every turn.

Reading Zambreno, hearing my cohosts’ quite different response to the book, feeling puzzled at my resistance to this book and others like it, I wondered not for the first time what it is about autofiction that doesn’t do much for me. I worry that I’m missing out—if this is the defining literature of the day, what would it mean to be, at best, ambivalent about it? My uncertainty sent me back to one of the passages that stayed with me, in which Zambreno writes, in the voice of a friend, a friend she can name, to whom she in fact dedicates the book, a friend different than the complicated, bad friend of the first part of the book, a friend who has indeed saved her (intellectual) life. The friend writes that

she has been reading contemporary autofiction in translation, Knausgaard, Éduoard Louis, Annie Ernaux. I’m making a study of coherence, she writes me. The extreme confidence of these writers, in the status of their art form, she writes. I’m obsessed with cracking the code of this security.

The cracked mirror of this passage feels like a key to Zambreno’s book, which enacts a struggle with coherence, offers itself as modest, the opposite of confident, unsure what her art form even is, or if it is art. Can a set of notes be art? Maybe the only time I cracked a smile while reading this book was when Zambreno, writing, I think, to the same friend, worries that Guibert and his coterie (Foucault in particular, who, after all, couldn’t stand Susan Sontag) would despise her. Who is she anyway? “I’m just a mom on a couch!” she wails, in not quite mock despair.

But that mom on the couch writes books that many of the best readers I know thrill to. Like other writers of autofiction, she seems to have taken up Barthes’s cry for books that offer “the novelistic without the novel” (throwing away the supposedly ungainly crutches of character and plot). Perhaps I am hopelessly devoted to what he calls “the readerly,” the classic text, replete to the point of self-satisfaction with meaning. (Viz my thoughts on Barrett.) Yet I can’t for the life of me see what the relation between the two parts of Zambreno’s book is supposed to be, or if it would matter if their order was reversed. The passage about autofiction seems implies that Zambreno, if her friend speaks for her, is similarly unsure. Or maybe the point is that it’s not Zambreno, but her friend, who feels this way. Is coherence—here a stand-in for the idea of aesthetic form—a plausible or laudable goal anymore? Or is it one of those things you can’t escape, in the way that Barthes, who haunts Zambreno’s book as much as he did Guibert’s life, put it in Writing Degree Zero: even the absence of style is a style?

The big questions might be insoluble, but thank god there’s always gossip, bitchiness, being catty. Guibert loved all of those things, and Zambreno traffics in them too, a little. Yet I found her anger more convincing than her snark. That anger is directed at economic life in America today: shitty insurance plans; he risks of pregnancy that are made more dangerous than they have to be by the forced precarity of so much work, like her adjunct teaching; the struggle for childcare and the way being a parent, especially a mother, in a society that pays lip-service to that labour without doing anything to make it bearable, saps the self and makes you hate everything and everyone. [As I revise these words, I read of a GoFundMe campaign to help Zambreno and her family escape an apartment where illegal levels of lead paint have harmed her young children. Heartbreaking. Infuriating.]

As much as I wish it were otherwise, I must confess that To Write as if Already Dead left me cold. Coming back to the book six weeks after reading it [when I first drafted this piece], I find I have things to say. But I’ve barely thought about it once since we recorded the podcast. Do you ever find yourself out of synch with other readers, including ones you respect a lot? What do you do then?

Jane Austen, Mansfield Park (1814)

The greatest books are the hardest to write about, especially months after the fact. What can I say? It’s Mansfield Park, it’s incredible! Honestly, despite the autumnal pleasures of Persuasion, I have to plump for MP as the Austen MVP. True, I’ve yet to read Northanger Abby but surely that’s not taking the award. I think it was Jenny Davidson who said that Mansfield is the great novel of graduate school, or the one that graduate students are most likely to identify with, being as it is about someone who lives on the sufferance of more powerful people. Fanny Price, c’est moi. (I’m no grad student anymore, but it’s taking me a lifetime to get out from under that mindset.)

Let me just rhapsodize/free associate a little. I’ll start with the characters. Tom Bertram, what a scoundrel, what else could he come to but a bad end? Maria and Julia, ugh. Edmund, oof, tough one, I mean he’s kindly, he really is, even when he can’t see what’s in front of him—but how can that relationship work? (Austen is nicely ambivalent about this in the last chapter.) Lady Bertram, greatest of all time. She leant Fanny Chapman! Pretty damn nice of her! Pug! Wonderful Pug! Sir Thomas, I kind of dug him even though I don’t think that shows me in much of a good light. Aunt Norris, what a piece of work, hiss boo! The Prices, bad fucking news, I knew it the moment they came on the scene.

The chapters in Portsmouth, in the crowded, absentmindedly loving, all at sixes-and-sevens house, such good stuff! The scene in the ha ha, tremendous suspense, perfect allegory for the perils of interpretation! All the stuff about theatre, preposterous and yet compelling: sometimes we get so into something that our passion becomes a problem. And Fanny, oh Fanny! What’s not to love?

Georges Simenon, Maigret and the Ghost (1964) Trans. Ros Schwartz (2018)

One of Maigret’s colleagues is shot dead. Turns out he’d been doing some off-the-books stakeout work. He’d been acting like a man who was on to something big. He’d never been a great cop, was always looking for a case that could really make him. Looks like he found it—but then it found him, as it were. Maigret investigates—as does Madame Maigret, who’s quite a presence here (they have a memorable lunch together), for she must console the dead cop’s widow, whom she doesn’t much like. There’s a lot more by-the-book police work than usual in a Maigret. Which I liked. I managed to sneak a few hours in the backyard with this book on a work day. I liked that even more.

Mark Haber, Saint Sebastian’s Abyss (2022)

Having had the chance to hang out with Mark a couple of times in the last months, I’d like to think of him as a friend, and so I can’t be objective here. But I’ll say that this story of two art historians, who start as comrades and end as enemies, after falling out over how to interpret the masterpiece of a (fictive) Flemish master, and indeed how to interpret at all, seems to start as a Bernhard or Albahari pastiche, but rises to become a moving depiction of mortality.

Lan Samantha Chang, The Family Chao (2022)

I don’t read much American literary fiction, a lot of it seems worthy and labored. And long! Takes ages to read those books, who has time for that? And who could be more at the center of American literary fiction today than Lan Samantha Chang? She directs the Iowa Writer’ Workshop, ferchissake! But this book, this book I loved. The Chaos have ended up in small town Wisconsin, where their restaurant has been embraced by all. Big success: hard work, enough money, three sons, what could be better? Well, a few things. The sons have been given expensive educations that they have variously squandered or made good on or are just setting out on. Dagou has become a chef and come back home. He’s a good chef, maybe a great chef, but that’s not what this restaurant needs. Ming works in finance in New York, cutting himself to the bone to be perfect. Baby James is a floundering pre-med who wants to make everyone happy. Winnie, the matriarch, has left her husband and moved into a monastery. And Leo, the patriarch, continues to dangle the prize of inheritance in front of his sons, especially his eldest, while relentlessly mocking them. He’s a shit, is Leo. When he gets locked into the old walk-in freezer that he has refused to get up to code and dies a cold, lonely death, everyone is shocked, but maybe also a little relieved. Except then Dagou is charged with murder. The family rallies around him even as the community recoils. A lot of secrets get spilled, especially a last-minute one that I didn’t see coming.

The Family Chao riffs on The Brothers Karamazov. I read the Dostoyevsky too long ago and with too little attention to be sure. But the comparison comes up in the novel itself, through salacious media interest, Chang thereby signaling that this shared structure shouldn’t be taken too seriously.

A fine novel about belonging with plenty of melodrama and narrative drive and some really mouthwatering dinner scenes—and one that is… not.

I had the pleasure of meeting Chang at the Six Bridges Literary Festival—she is brisk, smart, a little uninterested in others; this, her third novel, deserves its plaudits and more.

Elmore Leonard, Pronto (1993)

Since I’m doing this all out of order, check out my November review of its sequel to get a sense of what Pronto is like. This wasn’t bad—I most enjoyed how the main character shifts from likeable rogue to pain-in-the-ass loafer. Unusual.

Oscar Hokeah, Calling for a Blanket Dance (2022)

At a powwow in Oklahoma, the emcee calls for a blanket dance for his nephew, Ever, a single parent of three young children who has recently lost his job. Ever’s great-aunt watches with pride:

I’ve seen many blanket dances in my day, growing up Gkoi, but there was something especially heartbreaking about a single parent down on their luck. Many of us, most of us, could see ourselves in Ever, like we had either been where he was or feared we’d end up there. We were taught to give or else more would be taken. Streams of people walked into the arena, while drumbeats and voices filled Red Buffalo Hall. We crumpled bills in our hands and tossed them on to the blanket. We stood next to Ever and has three kids and danced alongside. Must have been a good thirty people out there. The line of people made a half circle around the drum. Ever and his kids stood to one side with the Pendleton blanket spread in front of them. Some gourd dancers moved through the arena, while the singers’ heavy and low voices carried through our bodies. We danced, the way Kiowas danced, when called by our people, by our ancestors, to help each other heal.

To help each other heal. That’s what Oscar Hokeah wrote in my copy of his book when he signed it for me, after the panel I moderated at the local literary festival. As with The Family Chao—Chang shared the bill with Hokeah—I wouldn’t have read Calling for a Blanket Dance if I hadn’t agreed to run the session. And that would have been a loss. This linked-story-collection-cum-novel is equally funny and full of hurt. Set in two towns in eastern Oklahoma, the book concerns the Geimausaddle family, part Cherokee, part Kiowa, part Mexican (all aspects of the writer’s own background). Hokeah, a real mensch, works for Indian Child Welfare in Oklahoma, experience that surely informed some of the most moving parts of the book. “Sometimes a blanket dance can fill up your spirit, and this was one of those moments,” the great-aunt concludes. I felt the same way about this debut.

Frédéric Dard, The Gravediggers’ Bread (1956) Trans. Melanie Florence (2018)

My memory of this is that it nods to Lost Illusions by way of Simenon, but I’ve basically forgotten all about it.

Good reading month, eh? McMurtry, Frank, Au, Barrett, Austen. And a bunch of others that were also worth reading. Talk me down on the autofiction thing, friends. Or do you agree?