I wouldn’t say I had a great reading year. I was on my phone too much, I was being anguished or avoiding being anguished about the myriad injustices of the world, which I knew too much and could do too little about. I travelled—maybe not too much but an awful lot, for me—which was often energizing and enjoyable, but also got in the way of reading.

I felt, in other words, that I had frittered away my one wild and precious reading life. I bottomed out in the middle of the year, regularly tossing aside books unfinished after having spent more time with them than they deserved or that I could find patience for. A querulous reading year, you could say.

And yet some things stood out. Links to previous posts, if I managed to write about it.

Dwyer Murphy, The Stolen Coast

A rare heist novel where the heist, though satisfying, isn’t the main attraction. I loved this stylish, smart, funny tale of a man who has put his Ivy League law degree to use in taking over the family business: giving new identities to guys on the run and getting them the hell over the border. A great book of off-season resort towns.

Simon Jimenez, The Vanished Birds

I’m still getting my bearing in contemporary sff so take these comments for what they’re worth, but it seems rare to me that a book takes as many swerves as this one: the narrative moves back and forward in time and all over the place, from a near-future nearly uninhabitable earth to a galaxy far-away in space and time. You get invested in a storyline and then it ends but sometimes it comes back. But even more than the structure I loved this book for its emotional seriousness: its many relationships are doomed to fail because of their constitutive circumstances. For example: a man ages fifteen years between each meeting with his beloved, while she, thanks to intricacies of stellar time travel, has only aged a few months. The emotions might be bigger than the ideas, but I was totally okay with that.

Two novels by Katherena Vermette

One of the greatest working Canadian writers. This year, fresh off the thrill of teaching The Break to smart, appreciative students, I read The Strangers and The Circle, a bleak and beautiful trilogy of indigenous life in the aftermath of the cultural trauma of the residential school system.

Four novels by Kent Haruf

It should tell you something that in early April, one of the worst times in the academic year, I read four novels by Kent Haruf in just over a week. I loved Plainsong the most but enjoyed Eventide, Benediction, and Ours Souls at Night almost as much. Easy reading, sure: plain syntax rising to gentle arias, nothing fancy, maybe a little sentimental. But these books are so warm and kind. Each is set in Holt, Colorado, out on the eastern plains, where the mountains are a smudge on the western horizon and it’s sometimes hot and sometimes cold but always dry. The people are ranchers and school teachers and social workers and hardware store owners and ne’er-do-wells and retirees. Everyone is white and no one thinks that’s worth noticing. The time is hard to pin down. Sometimes I thought the 70s or early 80s but we’re probably talking the 90s. Things were different before the internet. The characters’ lives are modest and they seem fine with that. They go about their business, do their work, make good choices and bad ones. People look out for each other, but they judge each other, too. Little kids get lost biking, but they come home again. It’s not all roses, though. High school boys bully girls into having sex, over in that abandoned house just down from where the math teacher lives. People get sick, go hungry, lose jobs. Some characters get what the preacher will call a good death, some die unreconciled to their kin, some without warning, too soon. Life just keeps happening, you know?

Some readers will call this hokum, but I ate it up. Haruf won my heart. I thought him especially good on second chances and unexpected turns of fate. Of all the stories that weave through these loosely connected novels, the best concerns two brothers, old bachelors, ranchers, who agree to take in a pregnant teenage girl and who, to everyone’s surprise, not least their own, form a new family with her. That scene where they take into the next town over to get things for the baby and insist on buying the best crib in the store? Magic.

Smart, sexy, stylish books about how we relate to bodies privately and publically, and whether we can recast the narratives that have shaped aka deformed our understanding of what it is to live in those bodies. Greenwell’s Substack is worth subscribing too; he makes me curious about whatever he’s curious about. Can’t wait for the essay collection he’s writing.

Emeric Pressburger, The Glass Pearls

Yep, that Pressburger. Closer to Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom than any of the (indelible) films they made together. Karl Braun, a German émigré, arrives at a boarding house in Pimlico on a summer morning in 1965. A piano tuner who never misses a concert, a cultured man, a fine suitor for the English girl he meets through work. I’m not spoiling anything to say that Karl isn’t just quiet: he’s haunted—and hunted. For Karl Braun is really Otto Reitmüller, a former Nazi doctor who performed terrible experiments, a past he does not regret even as he mourns the death of his wife and child in the Hamburg air raids. Now the noose is tightening and Otto/Karl goes on the run… Suspenseful stuff; most interesting in this play with our sympathies. Not that we cheer for the man. But his present raises our blood pressure as much as his past.

A short book that covers as much ground as an epic; a historical novel that feels true to the differences of the past but that is clearly about the present; a classic modernist Morrison text, where the first page tells you everything that’s going to happen except that it makes no sense at the time and the rest of the reading experience clarifies, expands, revises. Such beauty and mystery in so few pages.

Roy Jacobsen’s Barrøy series (Translated by Don Bartlett and Don Shaw)

Cheating a bit since I read the first one in December 2022. I’m a huge fan of these novels about a family and the remote Norwegian island they call home from 1900 to 1950. I like books where people do things with their hands, maybe because I can’t do much with mine. The characters bring sheep into the upper field, fish with nets and line, salt cod, keep the stove burning all through the year, row through a storm, carry an unconscious man through sleet. It’s all a little nostalgic, a little sentimental, but not too much. Just how I like it.

Two Books by Walter Kempowski (Translated, respectively, by Michael Lipkin and Anthea Bell)

Fresh on my mind so it’s possible I’ve overvalued them but I don’t think so. All for Nothing, especially, is something special.

George Eliot, Middlemarch

Last read in college—under the expert tutelage of Rohan Maitzen, this can only be called one of the highlights of my undergraduate experience. This time I listened to Juliet Stevenson’s recording, which perfectly filled a semester’s commuting. True, Arkansas traffic is not the ideal venue for some of Eliot’s more complex formulations, but Stevenson (as much a genius as everyone says, she do the police in different voices, etc.) clarifies the novel’s elegant syntax and famous images. The book’s the same, but I’m not; a whole new experience this time around. Much funnier, especially its early sections. (Celia is a triumph.) More filled with surprising events: that whole Laure episode (a Wilkie Collins novel in miniature), it was as if I’d never read it. And more heartbreaking: in 1997, I hated Rosamond, and I admit I still felt for Lydgate this time around, but I had so much sympathy for her, a character I’d only been able to see as grasping and venal. Speaking of sympathy, one of the glories of English literature lies in watching Dorothea as she matures from excitable near-prig to wiser and sadder philanthropist. Amidst all this change, though, some things stayed the same. Mary Garth still won my heart; the suspense at the reading of Featherstone’s will gripped me just as much.

It’s good to read Middlemarch in college. It’s better to re-read Middlemarch in middle age. It’s best to read Middlemarch early and often.

Konstantin Paustovsky, The Story of a Life (translated by Douglas Smith)

Six-volume autobiography of Soviet writer and war correspondent Paustovsky, a Moscow-born, Ukrainian-raised enthusiast of the Revolution who somehow made it through Stalinism to become a feted figure of the 1960s. The new edition from NYRB Classics contains the first three volumes. I only read the first two, not because I didn’t enjoy them (I loved them) but because I set the book down to read something else and the next thing I knew it was a year later. Paustovsky had something of a charmed life. His childhood was largely downwardly mobile, and he lived through so much terror and upheaval. And yet he always seems to have landed on his feet. Maybe as a result—of maybe as a cause—he looks at the world with appreciation. He can sketch a memorable character in a few lines. He writes as well about ephemera (lilacs in bloom) as about terror (I won’t soon forget his time as an orderly on an undersupplied hospital train in WWI). He can do old-world extravagance (the opening scene is about a desperate carriage ride across a river raging in spate to the otherwise inaccessible island where his grandfather lies dying) and the brittle glamour of the modern (for a while he drives a tram in Moscow). Trevor Barrett, of Mookse & Gripes fame, said it best: Paustovsky is good company. I really ought to read that third book.

A few other categories:

Didn’t quite make the top, but such pleasurable reading experiences: Adania Shibli, Minor Detail; Paulette Jiles, Chenneville; Abdulrazek Gurnah, By the Sea; Jamil Jan Kochai, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories (teaching “Return to Sender” was a revelation: fascinating how even students who had seemed immune to literature shook themselves awake for this one).

Read with dread and mounting desperation, don’t get me wrong it’s a banger, but couldn’t in good conscience call it a pleasure to read: Ann Petry, The Street. Barry Jenkins adaptation when?

Maybe not standouts, but totally enjoyable: Margaret Drabble, The Millstone; K Patrick, Mrs. S; Yiyun Li, The Vagrants; Elif Batuman, Either/Or

Best dip into the Can-con vaults: Margaret Laurence, The Stone Angel. Got more about of this now than I did in high school, lemme tell you.

Best book by a friend: James Morrison, Gibbons or One Bloody Thing After Another: Not damning by faint praise. It’s terrific!

Book the excellence of which is confirmed by having taught it: Bryan Washington, Lot. Maybe the great Houston book. I get that novels sell but I wish he’d write more stories.

Grim, do not recommend: Larry McMurtry, Horseman, Pass By; Girogio Bassani, The Heron

Not for me: Jenny Offill, Weather; Annie Ernaux, Happening; Yiyun Li, The Book of Goose

Planned on loving it, but couldn’t quite get there: Julia Armfield, Our Wives Under the Sea. Sold as metaphysical body horror, this novel about a woman who goes to pieces when her wife returns from an undersea voyage gone catastrophically wrong as a kind of sea creature didn’t give me enough of the metaphysics or the horror. I figured it would be perfect for my course Bodies in Trouble but I couldn’t find my way to assigning it. Possibly a mistake: teaching it might have revealed the things I’d missed. Gonna trust my instincts on this one, tho.

The year in crime (or adjacent) fiction:

Disappointments: new ones from Garry Disher, Walter Mosley, and S. A. Cosby (this last was decent, but not IMO the triumph so many others deemed it; he’s a force, but I prefer his earlier stuff).

Standouts: Celia Dale, A Helping Hand: evil and delightful, can’t wait to read more Dale; Lawrence Osborne, On Java Road: moody, underappreciated; Christine Mangan, The Continental Affair: moody, underappreciated; Allison Montclair, The Right Sort of Man: fun; Joseph Hansen: wonderful to have the Dave Brandsetter books back in print, hope to get to more in 2024; Richard Osman: as charming, funny, and moving as everyone says.

Maigrets: Of the six I read this year, I liked Maigret and the Tramp best. Unexpectedly humane.

Giants: Two Japanese crime novels towered above the rest this year. I didn’t write about volume 2 of Kaoru Takamura’s Lady Joker (translated by Marie Iida and Allison Markin Powell) but maybe my thoughts on volume 1 will give you a sense. Do you need a 1000+ page book in which a strip of tape on a telephone poll plays a key role? Yes, yes you do. (Also, it has one of the most satisfying endings of any crime novel I’ve ever read.) More on Hideo Yokoyama’s Six Four (translated by Jonathan Lloyd-Davies) here. Do you need an 800+ page book in which phone booths play a key role? Yes, yes you do.

The year in horror:

Victor LaValle, Lone Woman: horror Western with a Black female lead and not-so-metaphorical demon, enjoyable if a bit forgettable; Jessica Johns, Bad Cree: standout Indigenous tale, also with demons; Leigh Bardugo, Hell Bent: serious middle-volume-of-trilogy syndrome. Many demons, tho.

The year in sff:

In addition to Simon Jimenez, I liked Ann Leckie’s Translation State, Nick Harkaway’s Titanium Noir, and, above all, the three novels by Guy Gavriel Kay I read this summer, which gave me so much joy and which I still think about all the time.

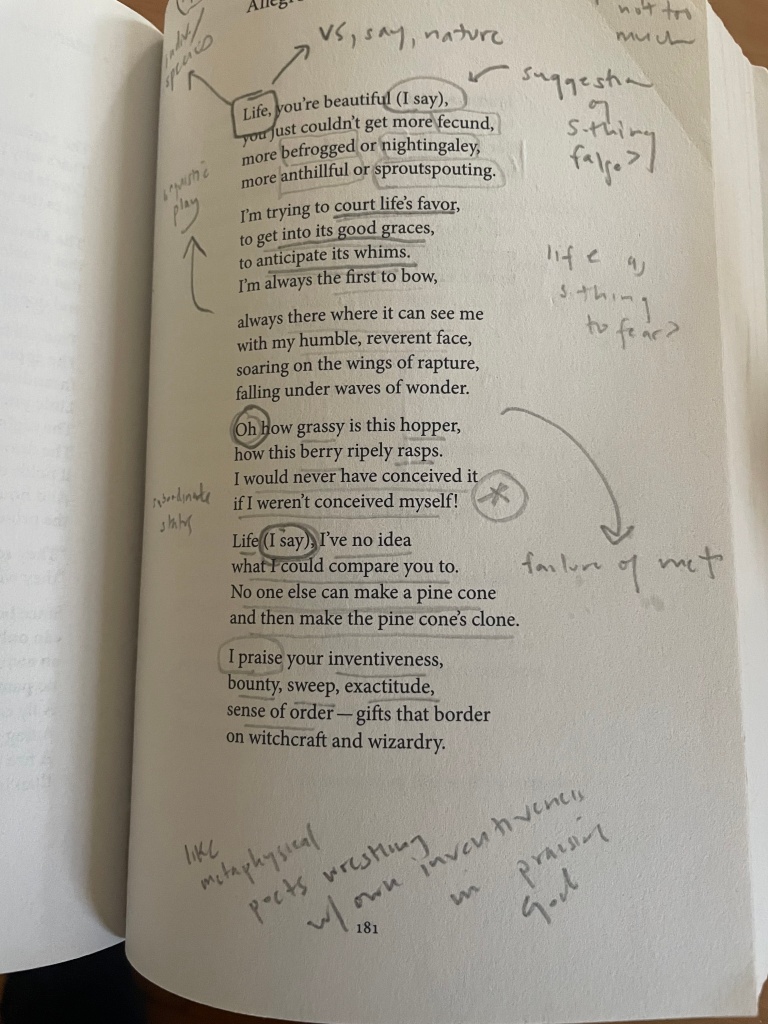

The year in poetry:

Well, I read some, so that’s already a change. Only two collections, but both great: Wisława Szymborska’s Map: Collected and Last Poems (Translated by Clare Cavanaugh and Stanislaw Baranczak), filled with joy and sadness and wit, these poems made a big impression, and Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic (fortunate to have met him, a mensch; even more fortunate to have heard his indelible performance).

The year in German books: I read two, liked them both. Helga Schubert, Vom Aufstehen: Ein Leben in Geschichten (On Getting Up: A Life in Stories), vignettes by an octogenarian former East German psychotherapist who had fallen into oblivion until this book hit a nerve, most impressive for the depiction of her relationship to her mother, which reminded me of the one shared by Ruth Kluger in her memoir; Dana Vowinckel, Gewässer im Ziplock (Liquids go in a Ziplock Bag): buzzy novel from a young Jewish writer that flits between Berlin, Jerusalem, and Chicago. The American scenes failed to convince me, and the whole thing now feels like an artefact from another time, given November 7 and its aftermath. I gulped it down on the plan ride home, though. Could imagine it getting translated.

Everyone loved it; what’s wrong with me? (literary fiction edition):

Made it about 200 pages into Elsa Morante’s 800-page Lies and Sorcery, newly translated by Jenny McPhee. Some of those pages I read raptly. Others I pushed through exhaustedly. And then I just… stopped. The publisher says it’s a book “in the grand tradition of Stendhal, Tolstoy, and Proust,” and I love those writers. (Well, I’ve yet to read Stendahl, but based on my feelings for the other two I’m sure I’ll love him too.) Seemed like my social media feeds were filled with people losing it over this book. Increasingly, I see that—for me, no universal judgment here—such arias of praise do more harm than good; I experience them as exhortations, even demands that just make me feel bad or inadequate. Increasingly, too, I realize how little mental energy I have for even mildly demanding books during the semester. (A problem, since that’s ¾ of the year…) I might love this book in other circumstances —I plan to find out.

Everyone loved it; what’s wrong with me? (genre edition):

Billed as True Grit set on Mars in alternate version of the 1930s, Nathan Ballingrud’s The Strange indeed features a young female protagonist on a quest to avenge the destruction of her family, but Ballingrud is no Portis when it comes to voice. True, I was in the deepest, grumpiest depths of my slough of despondent reading when I gave this a try, so I wasn’t doing it any favours. But that’s a nope from me.

Other failures:

Mine, not the books. Once again, I read the first hundred or so pages of Anniversaries. It’s terrific. Why can’t I stick with it? I read even more hundreds of pages of Joseph and His Brothers, as part of a wonderful group of smart readers, most of whom made it to the end of Thomas Mann’s 1500-page tetralogy. I loved the beginning: fascinating to see Mann’s take on the stories of Genesis; interesting to speculate on why Mann would write about this subject at that time. (For me, Mann is in dialogue with Freud’s Moses and Monotheism, another oblique response to fascism through stories from Torah.) My friends tell me it got a lot more boring shortly after I left off (the end of volume 2), but that’s not why I gave up. Turns out, I don’t do well if I’m supposed to read something in regular, little bits. I need to tear into books—and I wasn’t willing to make the time for this chunkster. Sorry, guys.

Odds & Ends:

A few albums that stood out: Roy Brooks, Understanding (reissued in 2022, but I’m not over it: this quintet, man, unfuckingbelievable); Taylor Swift, Midnights (I love her, haters go away); Sitkovetsky Trio, Beethoven’s Piano Trios [volume 2] (a late addition, but pretty much listened to it nonstop in December and now January).

After a decade hiatus, I started watching movies again. Might do more of that this year!

I was lucky enough to travel to Germany in late spring with a wonderful set of students. While there, I met so many people from German Book Twitter who have become important to me, including the group chat that got me through covid and beyond. (Anja and Jules, y’all are the best.) All these folks were lovely and generous, but I want to give special thanks to Till Raether and his (extremely tolerant) family, who took me in and showed me around Hamburg. (Great town!) Have you ever met someone you hardly know only to realize they are in fact a soulmate? That’s Till for me. What a mensch. Cross fingers his books make it into English soon. In the meantime, follow him on the socials!

Reading plans for 2024? None! I need fewer plans. I can’t read that way, turns out, and maybe I’ll avoid disappointment by committing less. Gonna be plenty of other disappointments this year, I figure. No need to add any self-inflicted ones. At the end of last year, I joined a bunch of groups and readalongs, because I want to hang with all the cool kids, but I can already see I need to extricate myself from most of them. One good thing I did for myself in 2023, though, was to stop counting how many books I read. I was paying too much attention to that number. Fewer statistics in 2024!

Finally, to everyone who’s read the blog, left a comment or a like, and generally supported my little enterprise (which turns 10 in a week or two…), my heartfelt. I do not know many readers in real life. You all are a lifeline.