It might have been in the first week of October, after another spirited conversation in my Holocaust Literature class, that I had to marvel at how far along we were in the semester for the students to still be bringing it like that every day. A special group. Good thing the classroom was giving me joy, because not much else was. The horrific terrorist attack by Hamas, the nightmarish Israeli response. Nothing but suffering, rage, self-righteousness, and apologetics. I found myself alienated from many of my communities. And then embroiled in a frustrating situation on campus (triggered by events in the Middle East but ultimately having nothing to do with it). Given all the bullshit it’s a wonder I got anything read at all.

Paulette Jiles, Chenneville (2023)

John Chenneville—scion of old French family whose estate, Temps Clair, lies north of St Louis in the fertile lands where the Missouri meets the Mississippi—returns from the Civil War after having spent nearly a year in hospital recovering from a terrible head wound. He finds his home in disarray: fields unplanted, animals untended, rooms empty. The only remaining servant gravely explains that Chenneville’s sister has been murdered along with her husband and their infant child at their home downriver at St Genevieve. From that moment, Chenneville devotes his life to avenging this loss (the subtitle states the case plainly: “A Novel of Murder, Loss, and Vengeance”).

The hero visits the scene of the crime (the bloodlands of the Missouri Ozarks that formed the setting of her novel Enemy Women), quickly learns who did it, and then chases the man, a sociopathic former sheriff named Dodd, across Arkansas, the Indian Territory, and into Texas. I know a lot of these landscapes, which was part of the book’s appeal for me, but I think Jiles’s descriptions are objectively lovely: evocative but spare. Nothing fancy, but clear as the sky on a frosty morning. Here’s Chenneville making camp after almost 24 hours on the go:

The wind was becoming sharp and hard; it bit at his lips and ears, his hands. It was bringing rain. To the south of the road he saw a motte of post oaks, great thick-trunked trees, and what looked like a declination of the earth toward a streambed. On that side he could build a fire and the smoke would blow away south and not alert any traveler coming down the road.

Remembering the advice of a sergeant, an older Mainer, he strips himself almost naked, putting the clothes under the blankets to keep them warm. Then come this lovely reflection:

For a few moments he felt again that suspended, almost magical feeling of being out in the wilderness and the weather and yet safe against it. Here was rest and a respite against bereavement because the world was going on without him in its deep rhythms, deeper than he could see.

I love this kind of thing. Chenneville has it all: a love story, a key subplot involving telegraphy, and a satisfyingly minor-key ending. (A final flurry of events, almost comically bathetic, renders vengeance unnecessary, and you can almost hear the protagonist sigh in relief.) The physical book is gorgeous, too, especially the stately maps on its endpapers. I almost regretted having checked it out of the library.

Wisława Szymborska, Map: Collected and Last Poems Trans. Claire Cavanaugh & Stanislaw Barańczak (2015)

So pleased I chose this as a selection for One Bright Book. I need to be encouraged to read poetry (too enslaved to the demon narrative); being accountable to Frances and Rebecca ensured I made my way through this collection of the Polish writer and Nobel laureate Wisława Syzmborska. To think what I would have missed out on otherwise!

Here’s some of what I said in my introduction to the episode:

Szymborska’s first poems were in the accepted socialist realist style; she later repudiated most of them, just as she rejected the doctrinaire communism she had espoused when younger. (From the 1960s on she was part of the Polish dissident movement.) Repudiation more generally was central to her artistic process: her published work runs only to about 350 poems. Asked about this, she said “It’s because I have a trash can.”

That dry, self-deprecating response seems typical of Szymborska’s personality—and indeed her poetry. A Polish friend tells me that her letters “fizz with joie de vivre” and I can see that quality in the poems too, even though they are often plenty melancholy. Despite that sadness, her poems are often funny, which makes me wonder what it’s like to read her work in Polish, since slyness or jokiness can be so hard to translate.

It’s said that the writer Czeslaw Miloz, himself a Nobel laureate (1980), was anxious when Szymborska won the prize, fearing she would experience it as a terrible burden, given her shy and retiring nature. Indeed, she didn’t publish any poetry for several years after the award. To me her later work is as strong as her middle period, so I certainly didn’t feel any loss in quality after the Nobel; I’m curious if you both agree.

Whether she felt the burden or not, I can’t say, but I can say that Szymborska’s Nobel Prize address is terrific: modest, humourous, but also totally on point. She writes, among other things, about how poets, like all people fortunate enough to do work they care about, are propelled by the phrase “I don’t know.” She adds, “I sometimes dream of situations that can’t possibly come true.” That made me laugh because she’s always doing that in her poems. Some of them even start with the word “if: if angels exist, would they care about human culture (she concludes they would only like early Hollywood slapstick). Some of them see the remarkable in ordinary situations, as in these lines:

A miracle that’s lost on us:

the hand actually has fewer than six fingers

but still it’s got more than four.

Or how with “a few minor changes” her parents might have married other people and then where would she be?

Other poems consider scenarios we don’t usually dwell upon—one imagines a baby photo of Hitler (“And who’s this little fellow in his itty-bitty robe?”); another speculates how many in a hundred people do or feel one thing or another, in the process humanizing the field of statistics; a third poem, called “Cat in an Empty Apartment,” concerns a cat whose owner has died. (Apparently, she told her partner, the writer Kornel Filipowicz, that “no living being has as good a life as the life your cat lives”—I suspect she wrote the poem in the aftermath of Filipowicz’s death in 1990. Heartbreaking lines: “someone was always, always here,/then suddenly disappeared/and stubbornly stays disappeared.”) The phrase “I don’t know” matters so much because it propels us to think and do more—specifically, to ask more questions. Szymborska adds, “any knowledge that doesn’t lead to new questions quickly dies out: it fails to maintain the temperature required for sustaining life.”

This phrasing too seems quintessential Szymborska. She was fascinated by life in its literal, biological sense: she writes about the specks of dust that make up meteors, about foraminifera, which, it turns out, are microscopic single celled organisms that build shells around themselves from the minerals in sea water, and about what she calls “our one-sided acquaintance” with plants: we think we know about them: our monologue with them is essential for us but never reciprocated; they don’t care about us.

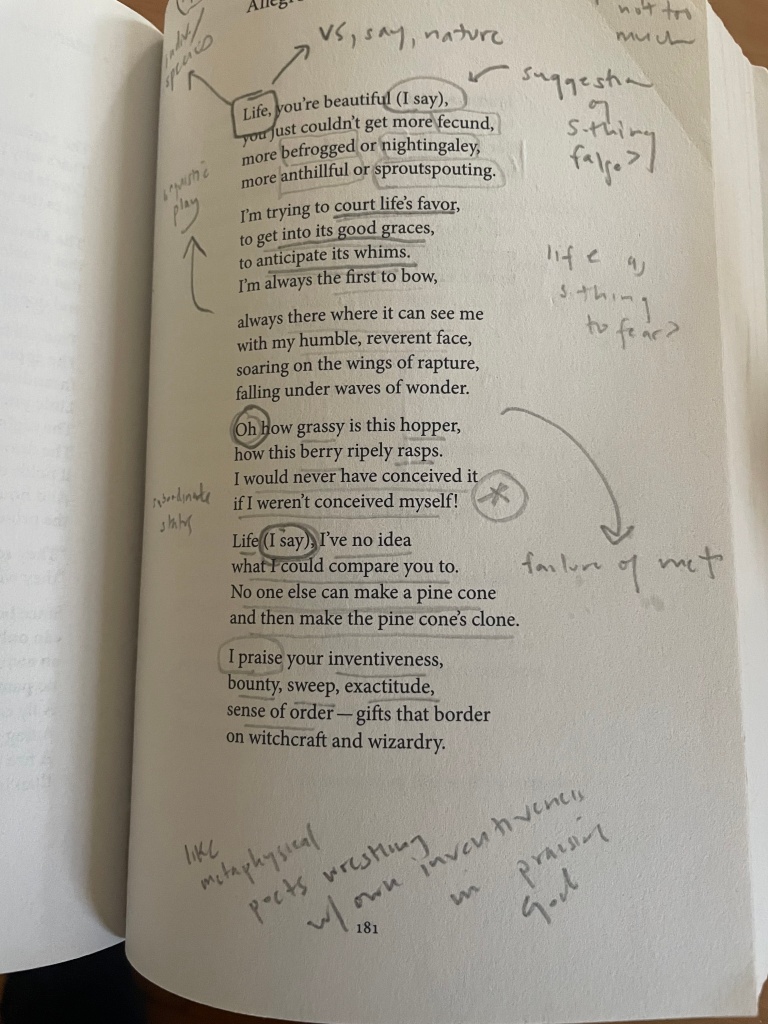

We each chose a poem to close read. Here are some of my notes on my choice, “Allegro ma Non Troppo” (1972).

Anyway, listen to our conversation here. Our best, IMO.

Allison Montclair, The Right Sort of Man (2019)

Kay recommended this to me, and I can’t improve on her review, which chimes perfectly with my experience of the book. In brief: two women, Iris Sparks and Gwendolyn Bainbridge, set up a marriage agency in London in the immediate aftermath of WWII. They know each other only slightly, it turns out, and as Kay notes, Montclair uses the opposites-attract and slow-burn tropes of romance fiction to explore their growing friendship and business partnership. The book begins with the eventual victim arriving at their office in search of a husband. Next thing you know, the woman turns up dead and suspicion falls on the client Sparks and Bainbridge have set her up with. (It doesn’t help that the murder weapon is found under his mattress.) The women set out to prove his innocence—and save their suddenly cratering business. The actual mystery is a little slight; I bet Montclair gets better at suspense as the series goes on. (I plan to find out.) Besides, as Kay also explains, the real interest here lies in the book’s melding of crime and romance. In addition to the leads, Montclair fills her book with strong minor characters: a heavy who just wants to be a playwright, a mobster who falls for Sparks, and a working-class guy who upper-crust Bainbridge meets while undercover. Part of me really wants these guys to come back, but part of me worries the series might fall risk to the whole “it takes 300 pages just to keep up with the antics of the growing cast of recurring characters” problem.

Prime light reading.

Giorgio Bassani, The Heron (1968) Trans. William Weaver (1970)

Dour novel of postwar Italian life, centering on Edgardo Limentani, a Jewish landowner who, having married out of the tradition, finds himself alienated by a political landscape comprised of communists that threaten his privileges and old fascists that respond to his continued existence with servility that fails to conceal their hatred of his continued existence.

On a damp day in late fall, Limentani goes hunting for waterfowl in the Po marshes. He dithers about going at all, finds himself waylaid, arriving too late for any good shooting, even, in the final account, unable to shoot at all, leaving it to his guide to bring down a trunkful of birds, which he later passes off as his own. On the way back he stops for coffees in a bar where he wrestles with whether to call the cousin he’s been estranged from for years, eats a meal in the restaurant of a hotel owned by one of those unctuous fascists, sleeps heavily and unsoundly in one of the upstairs rooms, and puts off returning home until his wife, whom he can no longer stand, will be sure to have gone to bed. From the time he starts awake in the pre-dawn dark until the time he returns to the study he uses as a makeshift bedroom, the protagonist thinks dark thoughts that give him no satisfaction. He sees no good way out of this life.

Having only read The Garden of the Finzi-Continis—a sad book, yes, but not a despairing one—I was shocked by this novel’s grimness. I’ve no idea about Bassani’s state of mind at this stage in his life, but The Heron (the title refers to a bird shot along with the ducks, no good for eating, pure waste) reads like the book of an unhappy and discouraged man. Maybe Weaver’s translation, getting on now in years, contributes to the novel’s heaviness. There’s a newish translation: anyone read it?

Billy-Ray Belcourt, A Minor Chorus (2022)

Score one for the “don’t give up on a book too soon” camp: I almost ditched poet and essayist Belcourt’s first novel after about twenty pages, annoyed at the clunky dialogue and risible self-righteousness (similar vibes to a book I really hated), but once the narrator leaves his graduate program in Edmonton and returns to his home community in way northern Alberta I started picking up what Belcourt was putting down. The narrator (an obvious stand-in for the writer) mines his community for stories to weave into the novel he’s writing: we hear from an older gay man, who unlike the narrator has chosen (or been made to choose) to stay closeted and both admires and disparages the narrator’s different decisions; an old friend who has disentangled herself from an abusive relationship; and his great-aunt, who worries over the fate of the boy she raised as her own, the narrator’s cousin, two boys who were once inseparable, but whose paths diverged (the cousin is in jail). In other words, when the narrator stops wringing his hands over whether his academic work can be meaningful in a world where so much injustice needs to be redressed and starts telling the stories of others as his way of doing that work, the book becomes moving and interesting.

I loved Belcourt’s descriptions of my home province, even though the part he’s from is about as far away from mine as Little Rock is from St Louis). This bit hit home:

The farther one veered from Main Street, a single stretch of highway on which sat most of the town’s businesses, schools, and amenities, the older the infrastructure became. Behind the dilapidated building ran train tracks that were less like sutures and more like wounds. It all looked so ordinary and Canadian and, because of this, haunted.

That passage gets better—more pointed—as it goes along. The workmanlike first sentence, as unvarnished as the buildings it references, gives way to a metaphor that asks us to return to the seemingly bland and official term at the end of the previous one. Who is the infrastructure that makes this place possible—improbable that people could live anywhere, but especially so in that northern clime—for? The things that link some people might separate others. (Who lives on the other side of the tracks?) The things that give some people meaning might just hurt others. Everything here leads to that last sentence: the ordinariness that many Canadians take pride in (unspectacular, solid, self-avowedly decent) is built on a foundation of dispossession and expropriation. And what of those who don’t see themselves in the mirror of that self-description? Those who are showy, marginalized, far from the main drag, maybe queer or nonbinary or indigenous. Is their only role to haunt Main Street?

James Morrison, Gibbons or One Bloody Thing After Another (2023)

I’m always nervous reading books by friends, but here I needn’t have feared: the debut novel by James “Caustic Cover Critic” Morrison is smart and engaging. It tracks the history of the Gibbons family from the late 1800s to an apocalyptic near-future in a series of chapters that work as stand-alone stories but gain in heft when the lines of familial affiliation come through.

Along the way, Gibbons serves as an alternative history of Australia in the modern era, referencing institutions and events ranging from the Native Police Force to the Snapshots from Home program to the devastating 1974 cyclone that nearly destroyed Darwin. I say “alternative” not because these things are made up but because the novel demands that we consider fabulation and creation necessary to any attempt to document the past. The first line, “A shelf of eyes, polished and unblinking,” alludes to the ability to see and record, even as it undermines these faculties: these eyes are fake, made of glass. Throughout the novel. James values the power of artificiality: not only are the pages filled with photographers and pulp writers and pornographers, but the chapters are separated by his own charming illustrations (and one by his daughter!).

It’s a good book, is what I’m saying. Shawn Mooney and I interviewed James to launch the book.

Holly Watt, To the Lions (2019)

The title of this engaging debut crime novel refers to the place journalists are willing to send anyone who comes in the path of a good story—and to the place they themselves are thrown when they go undercover. Cassie and her friend Miranda cover a specialized beat: the nexus of moral impropriety, tech bro/financial CEO untouchability, and third world suffering. Which makes a rumour that falls into their laps irresistible: somewhere someone is taking rich men to hunt people. Where? Like everything in the story, the location is obscure. A preserve, maybe. A prison. Or, as turns out to be the case, refugee camp. Through investigative reporting that Watt, a journalist herself, depicts plausibly and compellingly, the pair learn that the shadowy operation, though based in London, centers on a camp in lawless Libya, not too far across the border from a remote part of Algeria, where a private jet drops off the financiers, titled sons, and adventurers willing to pay a hell of a lot of money to do something whose repulsiveness makes them feel alive. To get the full story, though, the women need to catch someone in the act. A complicated undercover operation ensues, filled with menace (I’ve rarely been so scared for a character.) Watt plays with readers’ fascination with the lurid, which sometimes makes the book preachy, but mostly it’s just exciting. Not quite the usual thing, then, though it’s hard for me to see how Watt sustains her premise through the other books of the series. Just how many stories of this ilk can Cassie uncover?

Mary McCarthy, Memories of a Catholic Girlhood (1957)

Rebecca’s choice for One Bright Book; you can hear our conversation here. I was glad to have read this once-but-perhaps-no-longer-famous memoir, though I can’t say I loved it. I found it a desperately sad book about a family filled with people unable to communicate with each other. So many silences, so much heartache, so much harmful propriety. To my surprise, Rebecca and Frances found it funny and biting, a book filled with readerly pleasures. We didn’t convince each other, but I appreciated the chance to articulate my response. Many readers have admired the sections between chapters in which McCarthy explains what she later learned about the family stories she tells, pointing out inconsistences or outright falsehoods. Such self-awareness might have felt innovative at the time, but to me they didn’t add much. I think none of us expects memoir to be complete truth. Anyway, I will never forget the story of an uncle by marriage who sets out to show nine or ten-year-old McCarthy in the worst possible light, just so he and his wife could beat her black and blue with a hairbrush. Terrible, terrible stuff.

A wide-ranging reading month, with plenty to appreciate. Only Map really stood out for me, though. Any takes on these selections?