How I’ve lived 45 years without reading Willa Cather I do not know. But now that I’ve read My Ántonia (1918)—some impulse made me slip it into my suitcase just before leaving for vacation last month—I plan to make up for lost time. Because if this book is anything to go by, Cather is the real deal. As much as I’m chagrined to have taken so long to read her, I’m excited that there’s quite a lot of her to read.

(The other night I read the first 30 pages of O Pioneers!—clearly, she was a genius right from the start. If you have a favourite, let me know in the comments.)

Two things about My Ántonia really struck me: its descriptions of the Nebraskan prairie in the late 19th century, and its unusual narrative structure.

The book is narrated by a man named Jim who shares Cather’s biography; like Cather, Jim leaves his home in Virginia at age nine or ten (unlike Cather, he is orphaned) and goes to live with relatives in Nebraska, back when the land was barely plowed and not at all fenced in. My Ántonia is filled with evocative descriptions of the landscape, in its beauty and menace.

Consider this famous passage, from the end of the first chapter. Jim has arrived in the middle of the night at the station in Black Hawk, Nebraska, where he’s met by his grandfather’s hired man. He’s tucked into a kind of bed in the straw of a farm wagon and sets out on the long journey to his grandparents’ homestead:

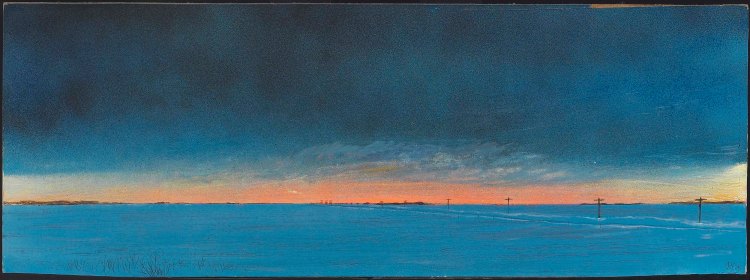

Cautiously I slipped from under the buffalo hide, got up on my knees and peered over the side of the wagon. There seemed to be nothing to see; no fences, no creeks or trees, no hills or fields. If there was a road, I could not make it out in the faint starlight. There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made. No, there was nothing but land—slightly undulating, I knew, because often our wheels ground against the brake as we went down into a hollow and lurched up again on the other side. I had the feeling that the world was left behind, that we had got over the edge of it, and were outside man’s jurisdiction. I had never before looked up at the sky when there was not a familiar mountain ridge against it. But this was the compete dome of heaven, all there was of it. I did not believe that my dead father and mother were watching me from up there; they would still be looking for me at the sheep-fold down by the creek, or along the white road that led to the mountain pastures. I had left even their spirits behind me. The wagon jolted on, carrying me I knew not wither. I don’t think I was homesick. If we never arrived anywhere, it did not matter. Between that earth and that sky I felt erased, blotted out. I did not say my prayers that night: here, I felt, what would be would be.

This is such a careful melding of physical and emotional geography, the featureless but evocative and powerful landscape mirroring, even inciting, a kind of acceptance of fate and loss. There’s something artless about the prose here, helped by the child’s perspective, though Cather doesn’t stay entirely within this point of view: that brilliant description of the prairie—“not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made”—seems to come from a more mature perspective. But the vivid descriptions of the landscape here and elsewhere in the book (terrible blizzards, glorious sunsets, lazy summer days by the river) aren’t simply offered for their own sake. Instead they are central to the book’s narration. Writing about a place in which indistinction or lack or differentiation is one of the dominant features seems to have allowed Cather to think in interesting ways about what it means to structure a story. Could she write a novel that didn’t follow the usual landmarks of fiction?

In the introduction to the Penguin edition I read, editor John J. Murphy cites what I expect is a famous passage in Cather studies. Reflecting on her life, Cather describes how she took the advice of the famous New England writer Sarah Orne Jewett, who, when they met in1908, urged her to write about Nebraska:

From the first chapter, I decided not to “write” at all—simple to give myself up to the pleasure of recapturing in memory people and places I had believed forgotten. This was what my friend Sarah Orne Jewett had advised me to do. She said to me that if my life had lain in a part of the world that was without a literature, and I couldn’t tell it truthfully in the form I most admired, I’d have to make a kind of writing that would tell it, no matter what I lost in the process.

Reading these lines after having finished the book, I thought they helped explain the uncertainty My Ántonia had incited in me. What kind of a book is this, I kept asking myself. I loved it from the start—it seemed like a more sophisticated and less politically troubling version of the Laura Ingalls Wilder books I’d adored as a child—but once I reached the halfway point I became increasingly puzzled. Why was the book telling me what it was telling me?

Jim’s ostensible purpose is to tell the story of the oldest daughter of the other family that had disembarked at Black Hawk with him that night, the Shimerdas, immigrants from Bohemia. From the start Jim is smitten with Ántonia, who has a kind of vivacity, a life force, for lack of a better term, that almost singlehandedly allows her family to survive the difficult and dangerous first years in a new country.

But as the book continues, Jim becomes more important to the story; as a man he has opportunities the many women in the novel (the characters it actually cares about) don’t. (Although this is a novel filled with powerful female characters.) Jim grows up, becomes enmeshed in the social life of the town his family moves too when he is a teenager, and eventually, as Cather did, makes his way to Lincoln to attend university. As Jim’s experience takes center stage, I thought the book might become a kind of second-rate Bildungsroman. I say second-rate because Jim isn’t a particularly interesting character. For a time he is involved with another eldest daughter of an immigrant family, a woman named Lena who Jim and Ántonia had known from childhood. For a time I thought maybe the book was going to become about her. (She’s quite fascinating.) But when that didn’t happen, I couldn’t figure out where Cather was trying to go. There didn’t seem to be any forward momentum, and the vivid descriptions of survival on the prairie that had so captivated me faded as the characters gained greater economic and cultural security.

At about this time I was lucky enough to have lunch with Joe from Roughghosts. Over pancakes and eggs, I started complaining about Jim. Why did Cather need him as a narrator? If Ántonia couldn’t tell her own story—and her inarticulateness, which is never understood by the book as a failure, suggests she couldn’t—why didn’t Cather make someone even more like herself the narrator? Specifically, why didn’t she use a female narrator?

Joe gently pointed out that I was missing the point—through Jim’s relation to Ántonia, Cather, who loved women all her life, possibly unrequitedly, I don’t know enough about her to say for sure, had found a way to queer her tale. Jim allows her to tell the book’s real story—about her own love for women, especially women like Anna Sadilek, the model for Ántonia—in a way that is at once more socially acceptable but also ultimately more interesting. Jim never gets together with Ántonia, never gets together with Lena, who for a time seems like a more or less satisfactory replacement for Ántonia (though, as I said, who is plenty interesting in her own right and exceeds our or at least my expectations for her). In other words, My Ántonia entirely avoids compulsory heterosexual romance. Well, almost. In the last chapters we return to Ántonia, who has, after a terrible experience, found a lovely, gentle man, married him, and produced a whole brood of children who the grown up Jim, now an unhappy Eastern sophisticate, spends his summers visiting, even becoming something like a sibling to them.

But this heterosexuality is almost invisible. (It is the privilege of heterosexuality to be invisible in the sense of being normalized, that is, accepted as the default state of things, but what I mean here is that it is invisible in and unimportant to the workings of the plot.) Ántonia’s remarkable fecundity is divorced from sexuality—her magnificent brood seems to have sprung directly from her own vivacity. I was struck by this description from the scene in which Jim first re-encounters Ántonia:

Ántonia and I went up the stairs first, and the children waited. We were standing outside talking, when they all came running up the steps together, big and little, tow heads and gold heads and brown, and flashing little naked legs; a veritable explosion of life out of the dark cave into the sunlight. It made me dizzy for a moment.

If sexuality is anywhere here it is in the bodies of the children (“flashing little naked legs”), but I don’t think we’re to imagine that Jim desires them—as I said, if anything he desires to be them, and in fact does so, I would argue, at the end of the book. Indeed, sexuality is almost always bad in this book—a sub-plot involving an attempted seduction, leading to a murder suicide brings this fact home.

What is valued instead is something like friendship or admiration, ostensibly between men and women but actually, it seems, between women and women. Yet even as I say that, I don’t think it’s correct. The book doesn’t just use Jim as a way to disguise Cather’s love for women. The book’s weirder than that. It’s about intense emotional currents, strong affections that don’t have any name. Friendship is the best we have but it’s a pretty paltry term for the relationship between Jim and Ántonia, who mean so much to each other but who spend most of the book living such different lives. And yet the book never presents their relationship as a missed opportunity. It’s not that they were meant for each other and should really have got together. After all, Ántonia seems perfectly content, inasmuch as that matters, with her husband. The more I think about the book the more strange, intense relationships it seems to contain: a lot could be said about Peter and Pavel, two Russians who flee to America after a terrible (and incredibly exciting, as well as stylistically distinctive—folkloric rather than realist) incident in which a wedding party is chased and mostly devoured by wolves. What’s going on with those guys?

I suppose this interpretation, if I can grace these thoughts with that term, would need to take into account the book’s title. What’s implied by the possessive? (My Ántonia.) We tend to think of ownership as being connected to domination. Certainly Jim has a lot more conventional societal clout (money, education, status) than Ántonia. But is she really his? She doesn’t seem to need him, or to be subservient to him. How does the non-normativity I’m arguing for include the possessiveness of the title?

Writing this post has made me want to read the book again, this time with pencil in hand in a more determined effort to understand its various parts. (I was on vacation when I read it, after all.) But I stand by my sense that the book’s depiction of landscape is connected to its interest in non-normative relationships, which leads it to take up a seemingly haphazard, even careless, and ultimately fascinating narrative form. I loved My Ántonia for the way it kept wrong-footing me and entertaining me as it did so.

You’re lucky to have these books ahead of you! I love Cather…Here’s a link to something I wrote about her.

https://theresakishkan.com/2014/05/31/singing-is-simply-a-sign-of-human-habitation-like-smoke-john-berger/

Thanks, for the link. A lovely post (lyrical, just like someone says in the comments). You’ve sold me on Song of the Lark.

I love Cather so much, and this post makes me want to go back to her yet again. You raise fascinating points about Cather’s choice of Jim as narrator and the novel’s sexuality–I need to mull them over some more. Joan Acocella wrote a great article about Cather for the New Yorker years ago (well before the publication, against her express wishes, of her letters), and even though I’m sure that reams more has been written about her since this 1995 piece, I still find it excellent: http://archives.newyorker.com/?i=1995-11-27#folio=056

Probably my favorite Cather novel is Death Comes for the Archbishop. But a lot of the short fiction is great too. I had my students read “Paul’s Case” in English 220. I thought they might find Paul’s portrayal dated or melodramatic, but they responded to him as a character and to the prose really positively.

Thanks, Hope. I look forward to the Acocella piece. (I don’t always like her stuff, but when I do I usually like it a lot.)

Death Comes for the Archbishop came up on Twitter as well. Clearly I need to check it out.

“Paul’s Case”! I forgot/didn’t realize she wrote that. I’ve actually never read it but I saw a PBS short film of it as a teenager and it made a big impression on me. I need to check that out again.

Cather reading project this year?

Fascinating! The only Cather I’ve read so far is ‘My Mortal Enemy,’ which I didn’t really understand very well. You rekindle the interest I had after I read it, though, in reading more (better) Cather.

Wow, I’ve never even heard of that one. How did you settle on it?

Man, you would pick one of the (admittedly many) books I’ve been trying to get through for years. You’ve given me added incentive to get back to it! (*bookmarks post to read in the year 2024)

Do it! It’s amazing. But I can wait until 2024 to hear what you think.

OK, I’m back and it’s only 2018, so I’m very proud of being 6 years ahead of schedule!

I too was curious about the strangely asexual nature of the relationships in the novel, and I think your explication of those elements makes a lot of sense.

I was less puzzled by the narrative structure- no doubt because I am less reflective, not because I understood it any better. My rather straightforward reading of the novel’s trajectory was as a move from the initial state of nature you describe towards an increasingly modern “culture”. Jim moves from farm to town to city to bigger city and returns home less and less frequently. Everybody seems to assume that Jim’s destiny is to become somebody important. Antonia thus embodies a past that anchors Jim, particularly because she lacks the desire/opportunity to leave it. From this point of view, it makes sense that Antonia is more interesting than Jim; she is the embodiment of a past that he has romanticized, while the present remains entirely uninteresting (he tells us virtually nothing about it). So I guess I see the novel as being about the increasing distance from the “origin” which Jim imagines being able to close at the end by envisaging a future with the Cuzaks. But the novel ends before he can fulfill his promises, and he has broken promises before, taking 20 years to return before this last visit. So that was my way of making sense of the structure, although there is some ambiguity there. I do agree that it’s a great book; this feeling of being both inextricably linked to the past and fundamentally cut off from it is handled with such poignancy. One really does hope he takes the boys fishing.

What a thoughtful reading, Nat! I wish I had the novel’s particulars more readily at my fingertips. (It would certainly merit re-reading.) I love the way you put the point about the novel’s structure as related to its interest in the past, and seeming lack of interest in the present. Part of me thinks that might explain how the novel avoids succumbing to nostalgia (because the present isn’t bad, it’s just nothing), but maybe that’s wishful thinking, because I’m susceptible to romanticizing the past. Do you think nostalgia plays a role in the novel?

Not sure I’m threading my response properly, but that’s a really interesting question about nostalgia. I would say that the novel is quite nostalgic, but not in a naive and uncritical way (which, I think, is maybe the same distinction you are making?) The novel seems not to be about idealizing the past, but about coming to an understanding of how we are shaped by our past; it is significant that it takes Jim quite some time to figure this out (he is away for 20 years before returning to see Antonia) and even longer, perhaps, to become fully conscious of it (his narrative comes about because of a chance meeting with a friend, and in the course of that conversation, he realizes that in order to tell Antonia’s story, he would have to present her from his own point of view and reveal quite a bit about himself; it seems that what we read is, at least in part, his figuring out the past through his narrative).

I just re-read the Introduction and realized that I missed two points: 1) We do know something about the present; Jim has a wife, whom he married to advance his career, is “temperamentally incapable of enthusiasm” and doesn’t love him, but doesn’t want to divorce him. So, his re-discovery of Antonia does seem to be a nostalgic retreat into an idealized world of family and honest work (one might almost call it a “mid-life crisis”). 2) Jim’s friend mentions that he “set apart time enough to enjoy” his renewed frienship with Antonia. This seems to suggest that he has followed through on his promise to return regularly (so the ambiguity I initially saw in the end really isn’t there).

But there is also something more than nostalgia, as this past is seen as the key to self-understanding, and the implication is that Jim has needed to grow in order to understand and appreciate the meaning of his experience. His return to Antonia (and perhaps also his return to that return through his narrative) seems to enable him to understand what he says in the final sentence of the book: “whatever we had missed, we possessed together, the precious, the incommunicable past”. On the one hand, the past is romanticized by asserting its incommunicability, but on the other hand, there is something forward-looking as well; what has been “missed” is not as important as what is “possessed” and what will be in the future (fishing trips with the boys, visiting foreign cities with Anton).

It is also worth noting Antonia’s own nostalgia for the Bohemian town that she was born in, which Jim is able to visit and take pictures of for her, but to which she presumably never returns. Perhaps the point is that nostalgia is inevitable, but it’s how we deal with that nostalgia that matters; rather than longing for an impossible return, Antonia creates a life for herself that incorporates elements of the old country in a new country, while Jim, through Antonia and her family, finds the space to incorporate elements of his old life into his new life.

A significant moment here is in the final section when Jim sees Antonia again and muses that she shouldn’t have left her farm as a girl to work in town because she always felt lonely in town. She responds that she is glad she went because of how much she learned (even if part of that lesson was to be less trusting because of her abortive first engagement). This is perhaps the same trajectory that Jim experiences; he has to leave and experience the modern world with all its flaws in order to appreciate the rural life of his childhood. (As a Romanticist, I’m inclined to insert a comment here about William Blake’s mythic structure in which one must pass out of a state of innocence and enter into the fallen world of experience in order to achieve a higher spiritual state.)

So, I do see a lot of nostalgia here, both on the personal level, and on the cultural level with its idealization of the traditional values of this settler culture against the modernity of New York and San Francisco. But it’s not a nostalgia that gets stuck in a melancholic longing for the past, but one that actively and productively works through the past in order to reach a greater sense of self-understanding.

Sorry, that was longer than I intended, but does that sound reasonable?

More than reasonable. It sounds completely convincing. I particularly like these formulations: “what has been “missed” is not as important as what is “possessed” and what will be in the future” and “t’s not a nostalgia that gets stuck in a melancholic longing for the past, but one that actively and productively works through the past in order to reach a greater sense of self-understanding.”

I just finished A Lost Lady (1923), where I was surprised to find that Cather had apparently read Dorian’s post and Nat’s comments and responded to some aspects of them in novelistic form.

Barely over 90 pages; easy to recommend. Cather has dropped Virgil and is back to Ovid.

Well, now I am curious! Nat’s comments have been making me feel the need for more Cather in my life, so this sounds like the place to go next.

I’m intrigued too! I will definitely have to look for that one.

I just realized I’ve never read any Cather books either. I will have to fix that. I like your story about having breakfast with Joe and your discussion of the book!

There’s always too much to read!

It was so nice to talk with Joe in person. I’d love to be able to do that with more of my online friends!

Thanks for the cameo! Reading this I want to revisit this book and read more of her work. Now you can see why I was so smitten with the ending. For a time I was worried that tragedy or some corny romance lay ahead. But Ántonia is such a resilient character and, in the end, she has a wealth and contentment that Jim, for all his privilege cannot find.

Cather is on my radar, but now I’m really keen to read this one. And how nice to hear about your conversation with Joe!

We talked about your day together. Sounds like it was terrific!

Such a fascinating piece! A little like you, I have come to Cather quite late in life, only reading her for the first time last summer with My Ántonia. As you say, she captured the landscape so well in all its beauty and brutality – that first winter was so cruel. The book’s structure intrigued me too, so it’s interesting to see your perspective on this. I loved the sections where Ántonia was centre stage, the others less so. I liked what she had to say about social change too, the opening up of new opportunities for independent women like Lena. If you’re interested, I wrote about it here:

https://jacquiwine.wordpress.com/2016/06/28/my-antonia-by-willa-cather/

Somehow I missed this the first time around, Jacqui. Terrific review as always. Maybe you unconsciously prompted my choice. (I always follow your reading, as my hopefully-soon-to-be-written post on Mollie Panter-Downes will suggest.) Anyway, I hear you about the draggy parts of the narrative, but as I wrote I think that’s part of something really interesting on Cather’s part.

Thank you. Maybe I did! 🙂

I can’t wait to hear what you thought of One Fine Day – I’m looking forward to that piece already.

While we’re on the subject of influencing one another’s reading choices, it was your recent interest in revisiting L. P. Hartley that prompted me to read The Hireling (I’ve just posted about it today). Did you get a chance to read The Boat during your summer break (I think you were planning a joint read with Nat)? If so, I’d love to know how you got on with it. There are some clear parallels between The Hireling and The Go-Between, especially in terms of the focus on barriers between people from different social classes — so I’m wondering if The Boat taps into similar themes?

Saw The Hireling review in my feed today but haen’t had a chance to do more than skim it. I’m still reading The Boat–halfway done, and I’m way overdue. Poor Nat has been finished for a while. I’m enjoying it but not totally wowed by it. It’s awfully long and so far I can’t tell *why* it’s that long. But it’s certainly about the relation between social classes, yes. In fact, I’m off to read more of it before bed. More soon, I hope.

I can tell you exactly why I did not read Cather for many of my 45 years – because I grew up too close to Red Cloud. Why would I want to read about, you know (gestures at surrounding landscape), here? I wanted to read about there, wherever there was. (Plus I did read “Paul’s Case” and some other stories in school, so the Cather box was checked).

The early stories in Troll Garden (1905), including “Paul’s Case,” are very much about Cather’s own ambivalence about “here” and “there.”

Funny, both Dorian and I grew up in western Canada with an environment and immigration history with parallels to that which Cather depicts. Bringing that pioneer era to life was something we both liked. In the home of the Calgary Stampede you get plenty of the mythology of the west—there is something more honest and raw in My Ántonia it seems..

I like it well enough now, but as, say, a teenager, or even a college student? Oh no, anything – anywhere – else, please.

Even now, while visiting Red Cloud recently, I thought “Don’t become a Cather scholar – your annual conference is here.”

If My Antonia is anything like O Pioneers!, it contains quite a bit of mythology – Greek mythology, which Cather loved.

That made laugh “Don’t become a Cather scholar – your annual conference is here.” In this regard I did well to become a Lawrence scholar. Except that I am a terrible Lawrence scholar and never go to the conferences in all the exciting places he lived.

Mythology–maybe, I probably missed it. But Virgil, definitely. The epigraph is from Virgil, and furthers the book’s theme of retrospection. I wrote a bit about that but then cut it from the post. Melissa could help us with the mythology.

Yes, but I agree with Tom that I would not have been nearly as into it as a Young Person. In fact, I hated “here” with a passion and only wanted “there.” But now that there turns out to be Little Rock I’m a lot more interested in here than I used to be!

I can relate to that. In fact because I’m still “here”, I am still attracted to “there” at times.

Well put.

What a wonderful review including the enlightening breakfast with Joe, I’ve long had this author on my wishlist and look forward to indulging that wish. What immense satisfaction in reading and reflecting on this novel you’ve shared, thank you.

Thanks, Claire. Very kind of you. Let me know if you read Cather. I think there’s lots to discover there!

I haven’t read My Antonia, but your thoughts in this post sound SO much like mine while reading O Pioneers! The feeling of a missed opportunity for a female narrator in particular (although you’ve certainly given me food for thought there), the presence of strong female characters who frustratingly float just near, but never in, the forefront of the story, and also the intense emotional undercurrent of otherwise plain, graceful writing – often simply about landscape, or seemingly uncomplicated exchanges between friends – that makes one want to put a name on what remains nameless. The same questions arose when reading Death Comes to the Archbishop, which may be my favorite of the two, but hardly has a female character in it (instead focusing on a deep, platonic relationship between two French clergymen in the Southwest).

Your quote in which she recounts her writing process is fascinating, and makes me wonder if her decision to “make a kind of writing,” which results in an almost formlessness, is what makes her prose seem almost modern and entirely consuming. In any case, you’ve certainly made me want to read My Antonia! Lovely post Dr. Stuber; thanks for it!

Thanks, Lara! I appreciate the kind words and hope you are well. Do read it–and let me know what you think. Your description of Death is very enticing!

Pingback: 2017 Year in Reading | Eiger, Mönch & Jungfrau

Pingback: Paul Wilson’s Year in Reading, 2020 | Eiger, Mönch & Jungfrau