Pleased to once again present reading reviews from some of my favourite readers. Today’s installment, his fourth, is by that titanic reader, the one and only James Morrison. James lives and works in Adelaide, on unceded Kaurna territory.

BEST BOOKS READ IN 2024: An Annotated Index of Limited Utility

Books—there’s never any end to them, despite my attempts to read them all. Of the 280-odd I read in 2024 (no, you get a life!), these are the best of those that were new to me. In order to make this as useful(?) as possible, in in the endless quest for cheap novelty, they are presented as annotation to an index of themes. [Ed. – Sorry, missed that last bit. Still thinking about the 280…] Four writers appear twice (Kate Kruimink, Joseph Roth, Percival Everett and Walter Kempowski) and for what I think is the first time, both parties in an extant marriage also make the list (Everett again, with Danzy Senna).

Age, Coming of: Gwendolyn Brooks, Maud Martha & Diane Josefowicz, L’Air du Temps

Two opposing approaches to stories of young girls growing up. Brooks’s 1953 novel is a collage of vignettes stretching over years, the growing up of a Black girl in Chicago, unlucky but resilient, dreaming of a high-class life in the face of her own limited opportunities, Josefowicz’s novella covers just a short period of time in the life of a 13-year-old girl, when the shooting of a neighbour proves to be the catalyst for the peeling back of various local secrets. Brooks was primarily a poet and Josefowicz is a historian, but both of them show themselves to be tremendous fiction writers.

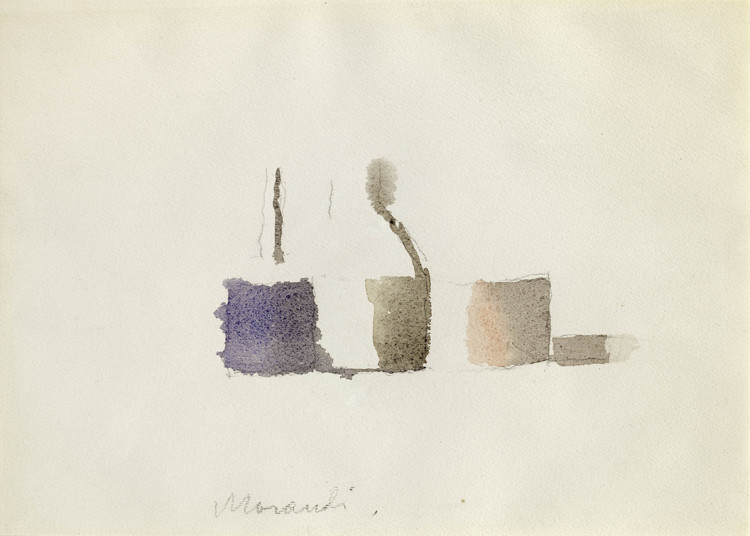

Art, Making of and Prehistory of: Maylis de Kerangal, Painting Time (translated by Jessica Moore)

De Kerangal is a personal favourite, and her best books usually involve a deep dive into some fascinating technical process (organ transplants, restaurant-level cooking, infrastructure engineering, or, in this case, both ancient cave art and trompe-l’œil painting), balanced with beautifully judged explorations of its human pressures and consequences. A compressed, deeply involving history of visual trickery and the impulse to make art.

Art, Making of from Deceased Father’s House: Jen Craig, Wall

In 2023 Craig’s two earlier novels were among my most loved discoveries, and I wasn’t wrong in thinking her third book would also be fantastic. A woman who is and isn’t Craig herself returns home to Australia to empty out her dead father’s house, with an eye to making the contents into an art exhibition. Multiple levels of consciousness rooted in different frames of time, deftly handled so as to be both convincing and presented with clarity, Craig’s prose is a wonder. I was lucky enough to be able to speak with her about one of her earlier books as part of the Wafer-Thin Books discussion series I co-hosted with Brad Bigelow of Neglected Books (neglectedbooks.com) through 2024—video here.

Biracialism, Literature of, Now an Award-Winning TV Series: Danzy Senna, Colored Television

Breezier in style than most of the books here, but far from shallow, Senna’s book features a protagonist obsessed with her own mixed-race nature, author of an undisciplined manuscript that’s becoming “the mulatto War and Peace.” She makes the mistake of getting involved with the Hollywood “prestige TV” world, and complications, as they say, ensue. Race, art, theft, infidelity; it’s all in there, making the sort of book that’s likely to be a big commercial success. Except this time it’s actually a good book. And yes, it does pain me to have to keep spelling the title the (wrong, but in this case “correct”) American way. [Ed. – They’re wrong, the Americans. And they will never admit it, James.]

Black Hole, Haunted by in Silicon Valley: Sarah Rose Etter, Ripe

A Silicon Valley satire—no, wait, come back! It’s well worth your time, and not just because the main character is haunted by her own personal tiny black hole, a physical manifestation of her depression. Things are not improved by her getting pregnant, nor by her various other ill-conceived life choices. A downbeat comedy of unforced errors.

Blitz: Francis Cottam, The Fire Fighter

Look, I have a weakness for Blitz fiction—people trying to go about their ordinary lives each day while having their world hammered each night by bombs is something I’m apparently able to read about endlessly. [Ed. – Same!] Cottam’s 2001 novel about a man given the task of protecting five specific London buildings from firebombs, without knowing why these sites are so important, is vividly convincing about the textures of daily life at the time, as well as exploring duty and treachery under ludicrously extreme circumstances. I’ve not read any of Cottam’s other books, which mostly seem to be supernatural fiction, but if they’re as strong as this they will not disappoint. (For more Blitz fiction, see Norah Hoult under Brains, below)

Boxing, Junior, Internal Thought Processes During: Rita Bullwinkel, Headshot

I enjoyed but didn’t love Bullwinkel’s story collection Belly Up, so if I hadn’t already bought Headshot I might have given it a miss. Yet again, incontinent book purchasing saves the day! [Ed. – As is so often the case!] Basically a series of internal monologues (though in the third person), from each of the teenaged girl contestants in an ill-attended second-rate female boxing tournament in a dusty gym over the course of one weekend, it’s a marvel. Kicks your Hemingway-style boxing crap out the door.

Brains, Decaying: Norah Hoult, There Were No Windows (also Cocktail Bar)

One of the Persephone Books rediscoveries that I can no longer afford due to most British people being dickheads and causing Brexit, thus making it prohibitively expensive to have British books sent to Australia, this 1944 novel by an Irish writer was both depressing and very funny, in the way that you can laugh afterwards about an awful relative, though their physical presence makes you squirm. It’s a pitch-perfect rendering of a deluded snob, hit with encroaching dementia and lowered circumstances, as the German bombs fall on London and servants become scarce. [Ed. – Oof, this sounds like something that might be called “unflinching”!] It was so good I immediately bought her story collection Cocktail Bar, from 1950, and it was similarly full of great things.

British People, Fucking Up Overseas in the Face of Imminent Implied Arachnid Apocalypse: Olivia Manning, The Rain Forest

Olivia Manning, man, such a great writer. Why isn’t all her stuff in print, instead of mainly just the (admittedly brilliant) two Fortunes of War trilogies? The Rain Forest, from 1974, is an intriguing twist on her common theme of a not entirely well-matched married couple doing duty for Britain overseas, in this case in a thinly disguised Madagascar (there are lemurs). Well-meaning ineptness in the face of political intrigue shades into an unexpected hint of global catastrophe to come from humans encroaching into a reservoir of toxic biology deep in an unexplored forest. Wonderful stuff. [Ed. – Wow! Sounds amazing! I, for one, welcome our imminent arachnid overlords.]

Century, Twentieth, Horrors and Absurdity of: Patrik Ouředník, Europeana (translated by Gerald Turner)

When spellcheck can’t cope with the author name or the title, you’re doing something right. Europeana is a brief but rambling survey of the Twentieth Century in all its ghastliness, where every fact, major or minor, is given equal weight, like a lecture by the most brilliant autistic raconteur in the world. If, like me, you buy the Dalkey Archive Essentials edition, you can also enjoy the brutally trimmed pages that slice off the outer edges of the marginalia.

Convicts, Female, Transcontinental Aquatic Journey of: Kate Kruimink, Astraea

The first of two Kruiminks on this list (see Grief, below), and the inaugural winner of the Weatherglass Novella Prize, this is the entirely shipbound story of a group of women being transported to New South Wales (not Tasmania, as every single review incorrectly states) in the early 1800s, to be servants and breeding stock in the new colony. Plagued by overbearing and/or predatory men in the shape of ship’s captain, crew, and minister, and haunted by their own miseries and guilts, their story is nevertheless a darkly funny one, full of unexpected insights and, for the reader, delights. [Ed. – Yep, getting this one for sure.]

Displacement, Linguistic, Psychological Aftereffects of: Antigone Kefala, The Island

Antigone Kefala is a (deep breath) ethnically Greek Romanian cum Australian via post-WWII refugee resettlement camps, writing in English, her fourth language. This 1984 book, being reprinted in North America this year, is, inevitably, out of print in Australia. It’s a subtle, destabilising, discursive meditation on place and belonging and language; very hard to pin down and quite unusual. [Ed. – Yep, getting this one for sure.]

Domestic Life, Oppressive Atmosphere Within: Fumiko Enchi, The Waiting Years (translated by John Bester)

A wife forced to choose and manage her husband’s concubine, who is still effectively a girl and not an adult, is the core of this disturbing but unsensationalised brief novel from 1957. Enchi was a distinguished, prizewinning novelist, and one of the great female writers of Japan. It’s criminal how little of her work is translated into English. [Ed. – Yep, getting this one for sure.]

Epics, Tiny and Incomplete: Joseph Roth, Perlefter (translated by Richard Panchyk)

This was the year that, despite pacing myself carefully, I ran out of Joseph Roth fiction. He was one of the greats, a genius and an alcoholic of astonishing powers, and the supreme chronicler of the Habsburg Empire, its collapse, and the darkness that followed. Perlefter is an incomplete novella, found in his papers and published posthumously, yet still substantial enough to hold its own. A wealthy Austrian, observed by an orphaned relative, enthusiastically grapples with the technological and social developments of the early Twentieth Century, all observed with Roth’s characteristically subtle and quirky eye and voice. See also Napoleon, below.

Failure, Artistic, Afterlives of: A. Valliard, The City of Lost Intentions: A Guide for the Artistically Waylaid

I can guarantee you’ve not read anything like this: a consistently inventive tourists’ guide to a netherworld of endless artistic failure and pretension, packed with more ideas per square inch than most books could even dream of, and written with a style recalling the sarcastically decadent fin-de-siècle classics. You’ll probably see yourself in it, and not be happy about it.

Grief, All-Enveloping Nature and Absurdity of: Kate Kruimink, Heartsease

Kruimink’s other novel of 2024 was the longer Heartsease, set in modern Tasmania [Ed. – Sure you don’t mean New South Wales???], and spikily hilarious even though it’s all about loss and grief and neglect. Wryly, unsentimentally Australian in the best way, and including a fine joke about musk sticks. [Ed. – Probably lands better if you know what that is.]

Lesbians, Ancient and Fragmented: Sappho, If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho (translated by Anne Carson)

As when trying to describe Ulysses in a previous one of these round-ups, sometimes there’s not a lot you can usefully say about a great book; you just have to point at it and marvel. I’ve read other translations of Sappho before, and loved them, but this really must be the ultimate take in English.

Life, Viewed Askew, in Small Portions: Jessica Westhead, And Also Sharks & Percival Everett, Half an Inch of Water

Two wide-ranging short story collections from the back catalogues of writers I deeply admire. Westhead is Canadian and belongs more to the George Saunders school of fiction (though better and more inventive), while Everett is much harder to pin down—if there’s any American writer working today with a broader, less predictable bibliography then I’ll eat any number of hats. Both books are full of gems, and are frequently genuinely funny.

Nanotechnology, Inadvertent Consequences of treating Cancer with: Anton Hur, Toward Eternity

An industrious and talented translator into and out of Korean, Hur’s first novel is cheeringly excellent: a full-on literary science-fiction exploration of nanotechnology, identity, social collapse, cloning, warfare, and the possibility of a human future, no matter how altered that definition of ‘human’ might be. It’s really enjoyable to see someone so talented engage with the genre in such a serious, productive way, though the results are often pretty bleak. [Ed. – Now I’m mad I had to return it to the library before I could read it.]

Napoleon: Joseph Roth, The Hundred Days (translated by Richard Panchyk)

The second Joseph Roth in this list, and something of an outlier in his work, being a fictional patchwork view of Napoleon through minor figures in his orbit, rather than being set in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Roth was always great, though, and stepping outside his usual area doesn’t dim his powers one bit. That I now have no fiction by him left unread is a cause of great psychological pain for me. Financial donations to ease my distress will be accepted. [Ed. – Please contribute to James’s GoFundMe. He asks so little.]

Nazis, Fleeing From in Company of Unreliable Man: Helen Wolff, Background for Love (translated by Tristram Wolff)

How did a book this good end up sitting for decades in a drawer, unpublished? Imagine a lost Jean Rhys novel, only with a female protagonist who has agency (alright, so it’s not an exact match) [Ed. – genuine lol], beginning with a couple fleeing to the Côte d’Azur one hot summer to get away from the growing Nazi power at home in Germany. Wolff wrote this book in 1932, but never tried to publish it, even though she later went on to found Pantheon Books in America with her husband. What other masterpieces like this are out there, sitting unpublished in a world where Haruki Murakami and Dan Browns’ every fart gets the hardcover treatment? Truly we live in a fallen world.

Nazis, Revenge on Collaborators with: Martha Albrand, Remembered Anger

In many ways this is ‘just’ an above-average crime/espionage novel, about an American man imprisoned by the Nazis who gets out at the war’s end and tries to find out who sold him out. But what lifts it above that is the fact it was written just as the events it was describing were happening, in the early months of 1945, as Paris wobbled back to the start of normality, by an author (born Heidi Huberta Freybe Loewengard) who was herself politically active against and then a refugee from the Fascists, and it beautifully captures the numerous little details of its time and place to give it a real kick of verisimilitude. [Yep, I’ll be getting this one, and actually reading it!]

Nazis, Rise and Collapse of: Walter Kempowski, All for Nothing (translated by Anthea Bell) & An Ordinary Youth (translated by Michael Lipkin)

A pair of stone-cold masterpieces, looking at Germans in World War II from opposite ends, geographically and temporally. Youth is about boyhood under growing Fascist power and then war, sneaking jazz records and trying to get out of the Nazi Youth, not for political reasons but because you don’t like enforced physical activity. Nothing, on the other hand, is the tale of the slow destruction of a German household on the Eastern Front as the Russians draw closer and closer. Both are wonderfully written, and attempt no form of exculpation of the author or the characters. These are people who didn’t like the Nazis because they were not their social class of person, not because of any ethical qualms. Youth is apparently part of a whole series of books Kempowski wrote in German, and we need all the rest translated NOW. [Ed. – Amen]

Palestine, Staging Hamlet in: Isabella Hammad, Enter Ghost

Even at the best of times trying to stage Hamlet in with an all-Palestinian cast under Israeli rule seems like a logistical nightmare, and these are not the best of times. A Palestinian-born, London-based actress returns to her birthplace and her sister, and almost involuntarily gets caught up in the theatrical project of a distant acquaintance, as well as attempting to reckon with her family and its history. It made me immediately buy Hammad’s first novel, The Parisian, though I haven’t read it yet because it’s huge. [Ed. – I just bought this too, and it’s so huge!]

Sanatorium, Satire of Male Attitudes Within: Olga Tokarczuk, The Empusium (translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones)

I get the feeling not everyone loved Tokarczuk’s latest book translated into English, but it was very much my kind of thing. A bunch of guys, self-deluded and not as smart as they think they are, discussing the issues of the day and their philosophies, while living in a tuberculosis sanatorium? A strange, supernatural observer/narrator? Sign me up!

Slavery, Literature Of, Remixed: Percival Everett, James

On the other hand, pretty much everyone seems to have loved this, and rightly so. As I mentioned above, Everett is one of the least predictable writers alive, and his take on Huckleberry Finn from Jim’s code-switching point of view is a gripping, funny masterclass in rewriting a classic without redundancy. This is an angry, exciting and surprising book that doesn’t always match the original’s plot. I hope this gets the author the huge audience he deserves, though it’ll also be funny to see this bigger audience attempt to process some of his earlier books.

Smallpox, Alternative History of World Due to: Francis Spufford, Cahokia Jazz

You know those stories where what begins with a couple of beat cops investigating a crime scene ends up being a whole-of-society-spanning investigation of conspiracy and political intrigue? Well, imagine one of those, written with the perfect mix of style, insight and originality. And it’s set in a version of history where it was the less virulent form of smallpox that was brought to the Americas by Europeans, meaning what has become the United States has done so in the face of much vaster, stronger First Nations. And imagine it’s a huge amount of fun. That’s Cahokia Jazz, baby. [Ed. – Look for this on my year-end list too!]

Troubles, The, Childhood During: Jennifer Johnston, Shadows on Our Skin

Jennifer Johnston is a writer who I idiotically ignored for years because her current UK publisher cursed her with the sort of soft-focus-photo-of-a-woman-in-a-fancy-dress-turned-away-from-the-camera-with-her-head-cropped-off cover photos more commonly found on flimsy commercial fiction. [Ed. – I prefer house-lit-from-within-against-a-nighttime-sky myself.] But then I came across a copy of How Many Miles to Babylon? with a good cover, read it, and was hooked. She’s phenomenally good, a brilliant and unsentimental Irish writer whose particular interest is the way the British occupation of Ireland leaks into and impacts upon the lives of ordinary people. Shadows is one of her best, following the life of a young boy in Derry in the 1970s, half in love with a school teacher who in turn is half in love with the boy’s older brother, who has come back home from England with big ideas and a gun in his back pocket. [Ed. – Damn, I just looked her up and she has so many books!]

Wildfire, Californian: George R Stewart, Fire

A Californian wilderness on fire, with the fire itself as the main character, and telling the story of all the people arrayed against or caught by it. Stewart, who also wrote Earth Abides (a wonderful novel and now a terrible TV series), describes everything with a dispassionate but not cruel eye, and the result, published in 1948, is all too horribly relevant now.

[Ed. — Ladies and gentlemen, give it up for James Morrison, always all too horribly relevant! Seriously, thanks James, this was amazing and budget-busting, as usual.]