Even if you got your fill of Döblin in my post, I urge you to read Nat’s shorter and smarter post on the same novel.

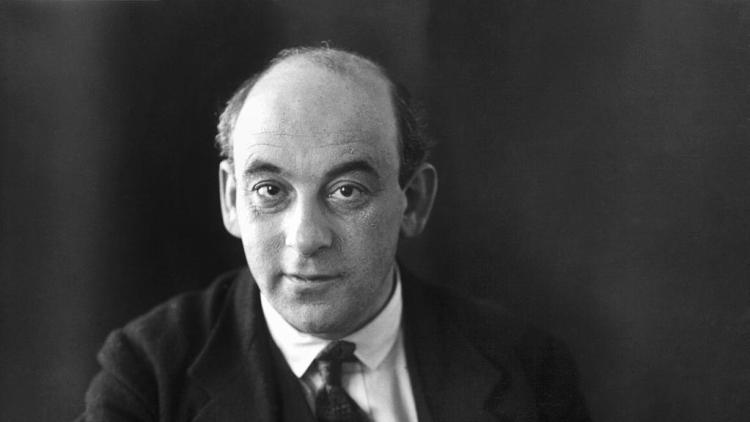

My excitement about Michael Hoffmann’s new translation of Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz can be traced to my very first day of graduate school. In a course on the fundamentals of critical theory, we were shown one of the opening scenes of Fassbinder’s adaptation, in which the protagonist, Franz Biberkopf is lying on the ground, being told a story. It seemed like a strange choice for a course where we would be going on to read Kant, Hegel, Levinas and many other heavyweight philosophers, and I remember being puzzled about how this guy lying on the floor connected with the history of Western philosophy. It took some time for me to get over my bewilderment and realize that my resistances were coming from the excessive rationalism of my undergraduate self. In time, the professor of this course became my supervisor and mentor, and perhaps the most important lesson I learned from her was that the oblique, hidden, and seemingly chance connections between things are often more significant than relationships dictated by rationality and causality.

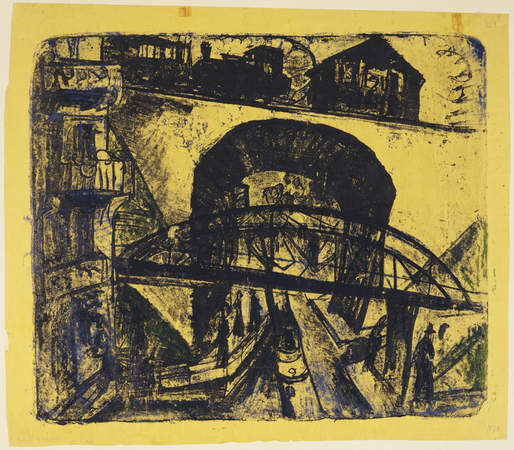

Not coincidentally, I’m sure, this is one of the lessons of Berlin Alexanderplatz too; although its main plot can be summed up fairly simply—Franz Biberkopf is released from prison, tries to go straight, but suffers a series of increasingly disastrous misfortunes—this narrative is continually interrupted by digressions that detail seemingly insignificant events taking place in Berlin at the same time, or that re-tell versions of biblical stories and other prominent narratives of Western culture. These narrative interpolations demand that we read Franz Biberkopf’s story within a very broad cultural context, but at the same time, the narrative mostly refrains from making any direct connections between the stories; we are never told exactly how we should read these digressions as bearing on Franz’s story, and they are in fact often highly ambiguous. For example, Döblin’s insertion of the story of Job invites us to think of Franz’s sufferings as being like those of Job, but we also can’t avoid reflecting on the fact that he is to some degree deserving of his sufferings, or that he completely lacks Job’s patience and religious perspective.

All of this is perhaps a long-winded way of explaining why, upon reading the book, I was inclined to attribute a particular significance to the story told to Franz in Chapter 1, even though I was also not surprised to find that it raised more questions than answers. Disoriented after his release from prison, Franz is helped by Eliser, a Jewish man who brings him into his house. Franz lapses into an almost catatonic state, and Eliser tells him the story of Stefan Zannovich, the son of an Albanian peddler, who launches an impressive career of social climbing by brazenly impersonating European nobility. Eliser concludes that “what you can learn from Stefan Zannovich is that he knew himself and he knew people”. This story thus seems to be a fable about autonomy, suggesting to Franz that he can control his own fate, and it is indeed instrumental in getting Franz back on his feet (literally, as he has been lying on the floor throughout).

It is not quite so simple, however; Eliser’s brother-in-law, Nahum, arrives during the telling of the story and insists that Eliser tell the end of the story, which is that Zannovich pushed his fraud too far, was found out, and eventually killed himself. For Nahum, the moral of the story is simply that “sometimes you can’t do everything you’d like to, sometimes things get fouled up”. Franz seems to hear Eliser’s message of hopeful autonomy and ignores Nahum’s warning, demonstrating both the power of stories and the danger of selective reading. But this is a highly ambiguous moment; it is not clear which of the brothers-in-law’s interpretations should be trusted, or indeed, if both are flawed. Nor is it clear whether Franz misreads Eliser’s intentions in telling him the story, or whether the story in fact has the desired effect. Nahum calls Eliser a “bad man” for telling the story, but Eliser’s intentions seem to be benevolent, even though Franz’s revival is somewhat questionable.

While the meaning of the story of Zannovich is ambiguous, what does seem clear, however, is that Franz has failed to understand it fully, and that if he has learned anything from it, the lesson is painfully incomplete. The narrator continually reminds us that Franz has greater punishments in store for him, suggesting, at the very least, that this story has not fixed what was wrong with Franz. Moreover, while Franz is grateful for the help, he also diminishes its significance: “these Jews helped me, just by telling me stories. They talked to me, they were decent people who didn’t know me from Adam, and they told me about this Polack, and it was just a story, but it was very good just the same, and it was very instructive for me in my position. I thought: a glass of cognac might have set me to rights just as well”. Not only does he call it “just a story”, he judges it by its results, which he deems could have been achieved by other means anyway.

Ultimately, as Eliser’s interpretation suggests, the point of the story seems to be to signal that this book is about the knowledge (or lack thereof) of self and others. But what exactly does it mean to “know oneself and know others”? Are these two different things, or are they connected? Is such knowledge to be understood as a philosophical ideal or is it merely instrumental and pragmatic? Is it significant that “self” is listed first, before “others”? Zannovich “knows others” in the sense that he knows how to manipulate them, while Franz’s understanding of others is almost always superficial and naïve. After being revived, he falls back on an overweening belief in himself that either exploits others, as in his string of relationships with women, or fatally misunderstands them, as in his toxic friendship with the womanizer and petty crook, Reinhold.

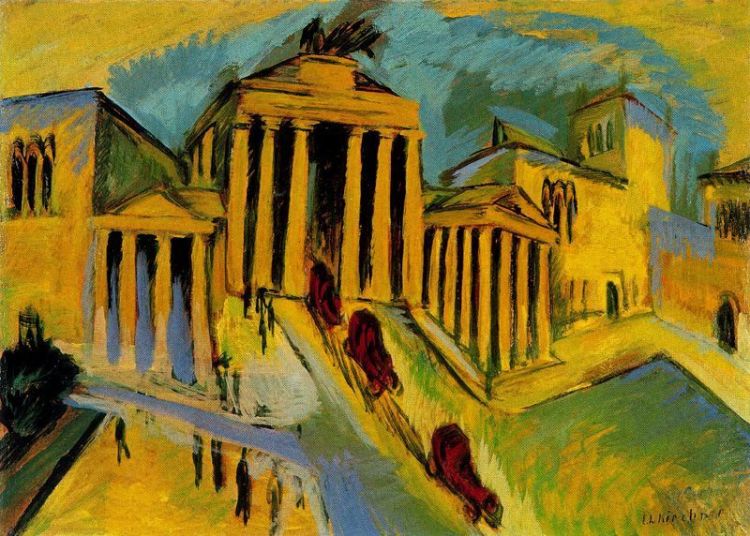

This lack of knowledge is apparent in Franz’s decision, immediately after his revival, to sell nationalist newspapers, “not that he’s got anything against the Jews, but he is a supporter of order”. While the book is not highly political, aside from a few pointed sections, I found it hard not to read Franz’s lack of self-knowledge in conjunction with the rise of National Socialism. Döblin, writing in 1928, is diagnosing the ills of a society about to be swallowed up by fascism, and one of these ills is the ugly and violent form of self-reliance embodied by Franz Biberkopf, whose lack of political conviction belies his philosophical kinship to fascism at this point in the book.

This resonance was developed for me by one of those oblique connections I mentioned earlier; while reading this book, I happened also to be reading Victor Klemperer’s The Language of the Third Reich, in which Klemperer poignantly describes the increasing circumscription of his rights as a Jew living in Germany, and his increasing immersion in his academic work to avoid the reality of Nazism: “why should I sour my life still further by reading Nazi publications when it was already being ruined by what was happening around me? If by chance or mistake a Nazi book fell into my hands I would cast it aside after the first paragraph. If the voice of the Fuhrer or his Propaganda Minister was blaring out of a loudspeaker on the street I would give it a wide berth, and when reading the newspaper I desperately tried to fish out the naked facts- forlorn enough in their nakedness- from the repulsive morass of speeches, commentaries and articles”. While I identified strongly with this as a reader in 2018 trying to avoid depressing news without entirely burying my head in the sand, it also made me think of Franz Biberkopf; if Klemperer, one of the most sensitive observers of pre-WWII Germany, can reproach himself with allowing himself to become too self-involved and overwhelmed by the media, how much more does Biberkopf in Döblin’s chaotic world embody this flaw? The polar opposite of Klemperer, Franz does not question himself, and when he does dabble in politics, selling newspapers or, later, agitating with his anarchist friend, Willi, he believes he knows all the answers. He is by no means inherently fascist, but he embodies a lack of understanding or caring about others that is easily manipulated by the much more frightening Reinhold.

The “example of Zannovich” (as the section heading calls it), then, is a negative one, deceiving Franz into believing that he is at the centre of the world, and enabling him to subordinate otherness to his will with a fascistic autonomy. (This is also pretty much the history of Western philosophy according to Emmanuel Levinas, so maybe that grad course really was on to something). Questions still abound, of course; for one, why does Eliser tell the story? Is he deceitful, or does he (like the narrator) foresee the necessary process that Franz must go through? If the novel diagnoses the ills of its society, it does so in order to suggest a solution of sorts, one that revises Eliser’s formula and makes the understanding of self and others inextricably linked.