Pleased to once again present reading reviews from some of my favourite readers. Today’s installment, her third, is by my friend Anja Willner. Anja lives and works in Berlin.

I’ve been logging my reading for seven years now. (A fairy-tale number, seven. I can’t name any other thing I’ve been doing for that long.)

2024 was different because burnout and depression ate up most of my year. [Ed. – So sorry to hear it, Anja. Lots of things to be depressed about and burned out by.] But thank god there’s always a but: And that’s the books that made it through the mind fog (doesn’t that make a great blurb) and stood out for me:

Christoph Ransmayr: The Terrors of Ice and Darkness (Die Schrecken des Eises und der Finsternis, 1984)

A great book about the price of discovery and adventure. The title is accurate, and if after reading it you still feel like starting your day with an icy shower or in a barrel filled with ice, I cannot help you. [Ed. – Ha! No fear there on my part!]

So you have this story about the Austro-Hungarian North Pole expedition going terribly wrong (skip this book if you feel strongly about dogs…) and getting almost no viable results, strung together with the story of a young Italian who goes missing while researching the same expedition more than a hundred years later. Some nice playing around with what is fact and what is fiction included.

(If you read this in winter, and your winters are still cold, make sure your heating works so you don’t get too authentic a reading experience.)

“Quiet” heroes

Something that almost always gets me is what you might call a “third row” hero: The protagonist is, at least on the surface, some ordinary person leading an uneventful life.

Of course, this only works if two requirements are met: First, the protagonist not really being dull (or so dull it’s already entertaining), and second, the writer is skillful enough to carry off this kind of story.

Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These was such a read for me. A quiet hero, a quiet life, but so much going on under the surface it’s almost impossible to lay the book aside. [Ed. – You hear people say „I read this book in one sitting a lot, and I feel like that must mostly be exaggeration, but I actually did that with this one!]

I’m also a sucker for narrators looking back on things not said or done in the right time. For me, J.L. Carr’s A Month in the Country is a gem full of wistfulness and melancholy (without self-pity), and musings about craftsmanship and memory, art and history. (It’s not so widely read here in Germany as it probably is in English-speaking countries.) [Ed. – Just going to leave this here…]

But hey, I don’t want this to sound dull (depression and books with hardly any plot, duh!) or as if I don’t like action-packed novels.

There was also my first Henry James! I had planned that ages ago, but I also wanted to read 300 hundred other things, and then… umm… life. [Ed. – We all know how that goes!]

Anyway, Portrait of a Lady. Wow. So many twisted marriage offers turned down in queer ways. So many plot turns, so many multi-layered characters (and the super creepy girl)! [Ed. – An action-packed novel indeed! So good, so pulpy, in its own way.]

I can’t help thinking James would have been great at scripting reality shows, and he’d also have to be in charge of the casting. Just imagine, a reality dating show written and produced by Henry James! I’d be so addicted I’d hardly get anything else done.

But back to supposedly “dull” books and on to one of my private reading obsessions: Anita Brookner novels. Despite crying for two days after reading my first Brookner in 2022, I’ve been sticking with her strange books.

Strange because often, they read like an abstract summarizing a novel or like a construction plan rather than like a novel in the flesh. Not to speak of her heroines (and occasionally heroes) whose rigidly organized lonely lives are so similar to one another I’m not always sure what happened in which book (not that it would matter very much, it’s not Henry James). Yet somehow, it works out great – at least for me. [Ed. – Amen!]

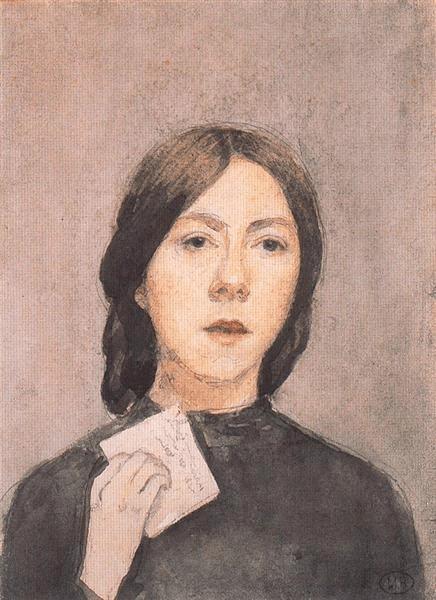

In 2024, I added three more Brookner novels to my reading log: Lewis Percy, Bay of Angels, and A Friend from England. Of those three, I liked Bay of Angels best (presumably the Brookner with the most sun, but that’s just the weather). Of course not as much as Look at Me, my all-time favourite of hers. [Ed. — Look at Me is hard to top!]

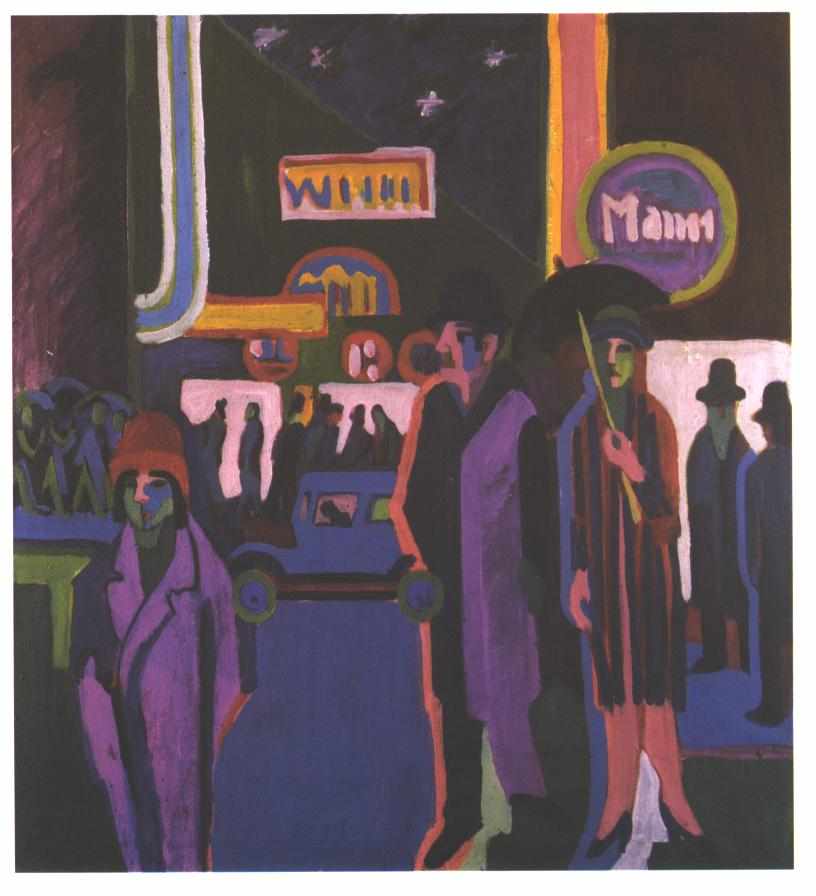

And finally, out of the brain fog emerges Nicole Seifert’s book about the women writers of “Gruppe 47” (group 47), an influential post-war German literary coterie. I already was familiar with some of the female members of “Gruppe 47”, but so many of them I was taught not to take as seriously as the alpha males who were the stars of the group, like Günter Grass.

In my reading log, I wrote down a single word about Seifert’s Einige Herren sagten etwas dazu (“Some gentlemen said something about it”): Brilliant. And I’ll stick with that. And boy, this book has led to some serious running after backlisted books! Meaning that I can never* buy a book again because I’ve still got two packages of literature waiting to be rediscovered standing around in my apartment. [Ed. — Tell us what they are in the comments, Anja!!!!!]

*never = not before the end of February 2025 or something like that [Ed. – That is modest indeed. I mean, it’s almost the end of February now! You can probably start reordering… Thanks for this lovely piece, Anja!]