Today’s reflection on a year in reading, poetic and stormy, is by Isaac Zisman. Isaac is a writer and editor based in Oakland, CA. Find him on all socials @octopus_grigori and at http://isaaczisman.com.

I confess to having a reticent memory. I keep few records. I should be more organized. Twenty-twenty-two was a year of reading—haven’t they all been? as well as I can recall—and yet I’m not sure it was a year of overmuch finishing. The year began in an overheated apartment in Manhattan. It could’ve been storming. Maybe lightning struck the tall building that everyone knows, everyone sees, the most witnessed building in history, perhaps, but whose name I here elide. A website I’ve never come across before says it was 55 degrees and raining at noon. It says nothing about thunder. I had Covid then, which meant I was on the couch under an old blanket. My partner prepared a small bite of caviar on toast the night before and I remember it only as texture.

I type in “books” into my phone’s camera roll and 534 images pop up. I add “2022” and the number drops to 136. Tapping “see all” brings them up in chronological order and so I can see I began the year with a small stack, my hand gripping the three books together above the sloping parquet of the apartment’s floor.

The first is I am writing you from afar: a novel graphic, by moyna pam dick, a gift from my friend Jared Fagen, a writer and the publisher of Black Sun Lit, the press who released the novel. My favorite page was one of four artful squiggles that appear to have been drawn with a weak Bic pen. Next in my hand is the Pevear and Volokhonsky translation of The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoevsky. I don’t think I made it past Father Zosima this go around. My copy of Crime and Punishment, ibid. trans. etc., sits next to it on the shelf now and I recall that in high school I thought it was a minor victory to take to the cover with a sharpie in order to change FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY into ODOR TOE. [Ed. – Big D would have been proud.] Thank god I left the spine clean. The third book is Janet Malcolm’s In the Freud Archives, in which a post-it note roughly lodged suggests I didn’t progress very far at all. [Ed. – Shame, it’s terrific!] I have the faint impression of a war between critics for mantle of Freud’s inheritance. I remember laughing at that.

Scrolling forward, my phone offers up mostly domestic scenes in which books appear. My partner eating soup at our little table next to the bookcase; the dog sprawled out beneath the same, his toys arranged on top of him in what was probably my idea of a joke; a giant pile of nachos at a friend’s apartment next to an edition of the Hokusai Manga, the astonishing book of figuration, expression, and Edo period garments by the painter of “The Great Wave Off Kanagawa.” In the background, the Los Angeles Rams square off against the Cincinnati Bengals, projected to nearly life size on the far wall. [Ed. – Ah, sportsball!]

On Feburary 2nd, I took a photo of single page of Ulysses (p. 489 in the Gabler edition, I discover, pulling down the book now from a high shelf). I’ve highlighted a name: “Isaac Butt.” [Ed. – Heh.]

Two weeks later I took a picture of String of Beginnings, the memoir of Michael Hamburger, translator of Paul Celan and basis of the character Michael Hamburger in Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn—for no representation can claim more than resemblance. I strikes me that I could steal the title for this little essay.

In March, friends online directed me to Guy Davenport—I’m sure you know these friends, perhaps you can count yourself among them. I picked up a copy of the guy davenport reader, primarily for the story “The Aeroplanes at Bescia,” a glorious assemblage of the fictional lives of Franz Kafka, the brothers Otto and Max Brod, and an atmospherically distant Ludwig Wittgenstein. For some reason, my hardback copy came wrapped in four identical dust jackets. I read around in Questioning Minds, Davenport’s lifetime of correspondence with the critic Hugh Kenner. My used edition of Apples and Pears, purchased later,contains a clipping—the author’s obituary in the Washington Post.

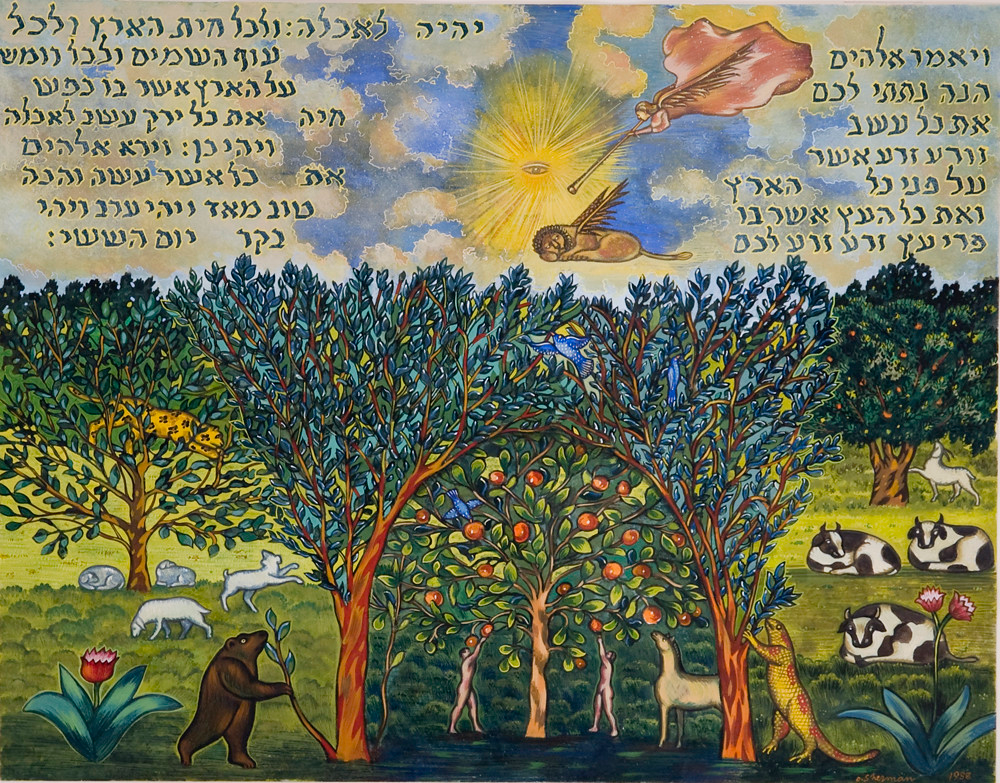

Late May found me in a strange version of a doctor’s office, a sort of wellness situation that goes beyond the purview of this text that I am writing now. The walls are adorned in a garish wallpaper and in my hand is a copy of the Zohar, though I can’t read Hebrew beyond sounding out the letters. I remember we spoke of being and becoming and that the doctor gave an impression of someone coming to poetry for the first time, his mind rigid with math and chemistry suddenly loosened at the core by the concept of metaphor. He liked to imagine beneficent angels, he told me.

On June 5th I bought another bookcase and took the stacks off the floor.

On June 10th I received a copy of Gordon Lish’s Peru from a seller on eBay. It smelled so rank I couldn’t bear to open it.

On June 16th I took a photo of an epigraph. “The first memory is of memory itself” –GIORGIO AGAMBEN. I have no idea to which book this quote attends.

In late June, we spent a week at a rental, a house on the New York State historic registry as it was once the home of Lincoln Barnett, a science journalist and editor for Life Magazine and the first to write a popular account of Einstein’s relativity for an American audience. It is possible that the great man, Einstein himself may have sat in this house, I thought as I leaned, head in hands at the old desk with its view of Lake Champlain and the sweet mildew smell of old books. Next to me sat my stack of Romanians—Mihail Sebastian, Dumitru Tsepeneag, Norman Manea, translations by Philip Ó Ceallaigh, Alistair Ian Blyth, Linda Coverdale. I composed half a chapter of my own book, adrift down a Dâmbovița of the mind.

By August I was reading Fosse again, this time Morning and Evening, trans. Damion Searls. I could not yet return to the Septology, also via Searls, the first volume of which had been my companion in the first weeks of the pandemic. If for Merve Emre reading Jon Fosse’s Septology was “the closest I have come to feeling the presence of God here on earth,” for me it was something different. The particular had exploded into the particulate. I have only been able to open it again now, but that is a reflection for next year. I am reminded, too, of the great Jewish mystic painter Ori Sherman and his series The Creation which depicts the seven days of Genesis. The last image is of the verdancy of the world, fecundity in potentia. God is at rest and emerging from the algal depths, from the swirling mass of green and blue signifying life and growth and wildness and all that is to come, ascends a radiant sphere. But it is neither the sun, nor the light of the world, nor of God, nor the gnostic light of secret knowledge. It is a crowned sphere inchoate, a virus. [Ed. — !]

Finding myself one of the few remaining residents at the end of a writing conference later that month, I laid claim to a stack of books abandoned by the side of a path. One of the novels was The Hundred Year House by Rebecca Makkai, who taught at the conference. At that moment, I saw her boarding a van to the airport and rushed over to greet her. I asked for an inscription, something I’ve rarely done. “To Isaac,” she obliged, “who stole this book!”

I returned to Lincoln Barnett’s house on the lake where I read Samantha Hunt’s mysterious essay collection, The Unwritten Book: An Investigation. Two days later, a cyclone descended, its epicenter the little spit of rock and soil on which the house perches above the lake. The windows blew in off their frames. Trees fell. Power lines draped across the road. The event lasted less than a minute, but we were trapped for days. We played scrabble and drank whisky and ate grilled hot dogs, the dented Weber, which the storm had flung across the yard and tipped to the edge of the small cliff at the far edge of the property, being our only method for cooking. I read Amit Chaudhuri’s Sojurn and dreamed of Berlin.

September was spent reading apartment listings. The Covid deals were gone. Rents had doubled, tripled. Our building had sold and was to become condos. We left Manhattan under a brilliant sky and headed back to California. In my backpack came a copy of Javier Marías’s A Heart So White, trans. Margaret Jull Costa, and as we drove toward the west, the smell of wildfire and dry grass, terrible and familiar, returned.

We arrived back in Oakland at the beginning of October, to the place where we’d lived before moving to New York, to the plague house of the first of the Covid years, and, before that, to nearly a decade of our lives. I returned to Bolaño and he carried me through the fall.

There were other things read, I’m sure, though the question of when exactly eludes me. I know, for instance, that I loved Emily Hall’s The Longcut, Jessica Au’s Cold Enough for Snow, Sublunary Edition’s magisterial edition of Marguerite Young’s Collected Poems. That I reread swaths of Hans Magnus Enzenberger’s Tumult, trans. Mike Mitchell, after his passing. That I read a long-travelled copy of Grimmish by Michael Winkler, sat enthralled by Sergio Chejfec’s My Two Worlds, trans. Margaret B. Carson, inhaled December by Alexander Kluge and Gerhard Richter, translation by Martin Chalmers. That I read the fictions of friends, sworn to secrecy until their much deserving publication. That I read essays and poems, criticism, lists of albums, cookbooks, articles, manuals, comics, menus, books of photography, road signs. The work of my new, online companions—how good it feels to have such talented peers. [Ed. – heart emoji] I see the silvered spines of the New Directions Storybook editions on the shelf beside me, I see the bookmark wedged somewhere in the first third of Mircea Cărtărescu’s Solenoid, trans. Sean Cotter—the image of twine emerging from the narrator’s belly button producing a shudder once again. On my desk the piles begin to grow once more—the books I pulled off the shelf to remember, the two translations of Clarice Lispector’s The Hour of the Star, Giovanni Pontiero and Benjamin Moser, respectively, the copy of Annie Ernaux’s Happening, trans. Tanye Leslie, that I read breathless in a single sitting as December closed. And the Septology, arriving again to start anew. It was a messy year, but edifying. What emerges next, I’m not sure.