April in Arkansas, azaleas in blossom, reading at the table under the trees. April in Arkansas: this is a feeling no one can reprise. Even though I’m making no progress on this book project, I wrote a lot last month, including essays on teaching the Holocaust and on a favourite book of mine that I once considered a secret. I wrote some other things that might come to anything, but I found the process useful and I also got a small piece of good news. I bumbled along, in other words. Here’s what I read.

Héctor Abad, The Farm (2014) Trans. Anne McLean (2018)

Three siblings take turns telling this story, which centers on La Oculta, a farm in the mountains of Columbia that has been in their family’s hands for generations. Pilar has kept the place going, even as she’s also worked alongside her mother in the family bakery; she has lived the life closest to the older generations, bearing children, married to her teenage sweetheart, a woman both capable and strong, good at everything from cooking to embalming. Eva has forged her own path, building a career, surviving various marriages and love affairs, becoming a single parent later in life. Antonio has escaped to New York, where he has made his way as a musician and settled down with a good man, yet despite, or because, of that distance he is the most drawn to the farm, making annual visits and taking on the task of unraveling the family history.

In alternating chapters, the siblings tell us about their pasts, their beliefs, their relationships to others. Put together, their narratives allow us to consider the competing forces of inheritance and invention. How much of who we are comes from the people and ways of life that came before us, and how much do we generate for ourselves? The novel delights in showing continuity—but it soars when depicting rupture. Even if the farm originated in a utopian attempt to generate community, Columbia’s violent past regularly interrupts daily life. This intrusion is most vividly evident in Eva’s memory of narrowly escaping a rebel attack on the homestead. (Terrific set piece.) Abad is a marvelous writer, and McLean a marvelous translator. I sunk into this sprawling novel—the beauty of the Archipelago edition adding extra sensory pleasure to the experience—and was sad when it ended.

Vanessa Springora, Consent (2020) Trans. Natasha Lehrer (2021)

Powerful memoir about the abusive sexual relationship between Springora and a famous writer whom she calls G. M. but is widely known to be Gabriel Matzneff. (Apparently, he was a big deal in the French literary scene; I’d never heard of him.) His identity as a “lover” of children was widely known too, at least among French artistic and political elites. These overlap much more than I, as a North American, would have expected; Matzneff had a letter in his wallet from Mitterand, lauding his artistic daring; he seems to have thought of it as a get out of jail card, except nobody ever put him in jail.

Matzneff’s career—he published several novels, all autobiographical, many overtly about pedophilia, as well as regular installments of his diaries—was built on the suffering of children and adolescents. Signora was one of many boys and girls he slept with, both in France and on sex tours in Asia; he was quite open about all of this. Springora met Matzneff in 1986, when she was 14. He seduced her intellectually, emotionally, and sexually; they were together for two years; the relationship damaged her badly, could, in some senses, have been said to have destroyed her life. This memoir proves it didn’t—but shows the cost. In fact, it was not until Springora realized that the way to get justice for herself was to speak in the only language that could touch Matzneff—that of writing itself—that she found any relief from her trauma. As she puts it, in a formulation comprising the grace and irony of classic French intellectual style, “Why not ensnare the hunter in his own trap, ambush him within the pages of a book?”

In so doing, she has had some effect, not only on Matzneff (he remains unrepentant, but the government took away a sinecure and his publisher dropped him) but on France more generally, where the book has been a best-seller and led people to acknowledge the ills that can be cloaked the mantle of freedom. In this regard, France’s so-called intellectual elite have a lot to answer for. The mantra of the 68ers, “it is forbidden to forbid,” was used by Matzneff to present child abuse as liberation, care, even love. A real who’s-who of the literary and philosophical scene signed open letters in support of these ideas back in the 70s. (Interesting that Foucault refused. Sad that Barthes did not.)

Consent, Springora observes, is an ambivalent term, sometimes signifying volition but often connoting something less than full agreement. After all, consent can be given on behalf of others, especially minors. Ultimately, consent is a mirage, a fig-leaf allowing those with cultural and literal capital to sweep away the reality of power imbalances. Consent is a sobering read, valuable for its indictment of the world that looked on while its writer suffered—from leering teachers to her overwhelmed and willfully blind parents. Its tone is uneven, sometimes epigrammatic, sometimes abstract, sometimes lyrical, but Springora doesn’t pretend to be a literary artist. That’s what she wanted to be, before Matzneff dispossessed her of her own words, not least by training her to write in a style he deemed timeless and elevated. (They sent each other hundreds of letters; he later published some of hers without permission.) To even consider Springora’s style feels fraught: to critique it is to risk playing the same game as her abuser (and his enablers), who argued that artistic beauty, passion, and fearlessness mattered above all. Yet it’s also important to advocate for style without thereby agreeing that its value trumps anything else.

Consent ends with a brief, illuminating afterword by translator Lehrer; I wish more books let us hear from the translator.

Flynn Berry, Under the Harrow (2016)

First of the three psychological thrillers by Berry I devoured this month. Under the Harrow is a fine debut; its tricksy narration makes it the most Highsmithian of her books. Berry’s prose is plain but not flat. Here the narrator looks out the window of a train:

Land streams by the window. Sheep arranged on the stony flank of a hill. The troubling clouds surging behind it. A firehouse with a man doing exercises in its yard. He pulls himself above a bar, lowers himself, vanishes.

The disembodied man, swallowed up by movement and perspective, is a suitably unsettling touch, offering a glimpse of what’s to come: the world the narrator thinks she knows is about to become similarly unmoored.

Guzel Yakhina, Zuleikha (2015) Trans. Lisa C. Hayden (2019)

My second Hayden translation in as many months; again, I read this as part of a Twitter reading group, and, again, I was glad I did. Zuleikha is a page-turner that comes at its historical events—the dekulakization of the peasantry under Stalin and the creation of the Gulag system—from what, I believe, is an unusual perspective. The heroine, who lends her name to the title, is a Tatar, a culture I knew basically nothing about; when I think of the famines of the late 1920s and early 30s, I think primarily of Ukraine, not Soviet Tatarstan. And since that culture is shown to be harshly patriarchal, Zuleikha is an even more intriguing, marginalized character. Too bad that the novel seems to find no way for Zuleikha to leave behind her status as “pitiful hen” and become as strong and independent as she does other than to abandon her Tatar identity.

Zuleikha is engrossing historical fiction that is never quite predictable. For example, it is more interested in relationships between mothers and children than between men and women. Its descriptions of the landscape are loving and evocative. Its plot is both eventful and uneventful: much of the action centers on how to survive—how to cut trees when your tools are bad; what to grow in a northern climate; how to hunt and gather on the land; even, in the days before exile, how to prepare the bathhouse for a steam session—but those everyday tasks take place against a backdrop where terrible events always threaten to intrude. In the end, I thought the “band of misfits pitches together against all odds” aspect of the story of the settlement was a bit cute. (Even though I still loved it.) And Yakhina’s use of focalization didn’t always work. We are mostly in close third person (present tense, natch, ugh), but that sometimes becomes implausible when Yakhina needs to tell us stuff that her heroine might not need or care to think about. Here she is in prison in Kazan, before being transported to Siberia:

The Tatar language is even constructed so you could live your whole life without once saying “I.” No matter what tense you use to speak about yourself, the verb will go in the necessary form and the ending will change, making the use of that vain little word superfluous. It’s not like that in Russian, where everybody goes out of their way to put in “I” and “me” and then “I” again.

There might be a point here about the role of the individual in resisting a collective system. Or maybe a critique of the project of Russianizing the Soviet Union’s plurality. Mostly though this moment is clunky. But I hope Yakhina’s second novel is translated soon. Hayden, who again generously offered her expertise to the Twitter group, would be the obvious choice to take on the project. Are you listening, Oneworld?

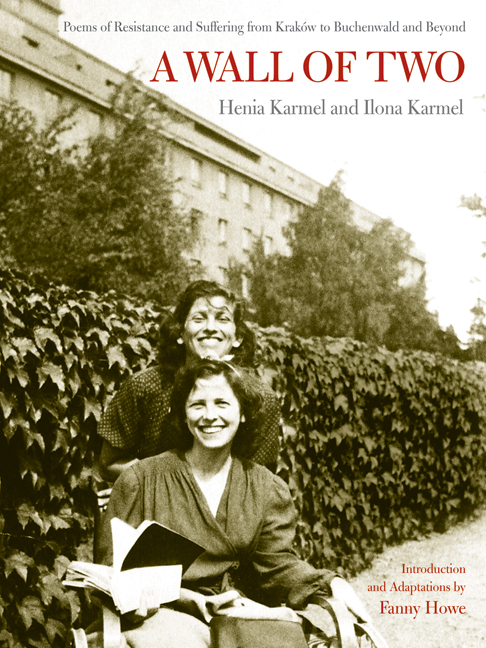

Henia Karmel and Ilona Karmel, A Wall of Two: Poems of Resistance and Suffering from Kraków to Buchenwald and Beyond Introduction and Adaptations by Fanny Howe Trans. Arie A. Galles and Warren Niesłuchowski (2007)

More about the Karmel sisters and their poetry here.

Flynn Berry, A Double Life (2018)

Berry’s take on the Lord Lucan case. Creepy and satisfying. Berry’s best, IMO.

Anna Goldenberg, I Belong to Vienna (2018) Trans. Alta L. Price (2020)

Another third generation Holocaust memoir. The difference here is that Goldenberg’s grandparents, after a short postwar dalliance in upstate New York, returned to Vienna, where their children and grandchildren still live. When Goldenberg herself moves to New York to study for an MA, people, other Jews mostly, ask her in appalled fascination: How can you [i.e., Jews] live there [i.e., among the killers]? Which prompts Goldenberg to speculate—not as interestingly as I’d have hoped—on what it means to belong, both to family and to place.

The other noteworthy thing about the story is that the most interesting person in it isn’t technically even in the family. When Goldenberg’s then 17-year-old grandfather, Hansi, received his deportation papers he ripped off his star, hopped on the streetcar, and made his way to a close friend, the pediatrician Josef Feldner. (Hansi had his parents’ blessing: they rightly suspected his chances were better in hiding. Indeed, he never saw them again.) Feldner, a Catholic child psychologist, was a remarkable man. He kept Hansi safe for the rest of the war, and prompted the previously mediocre student into his future medical career by taking the boy with him to see his patients, which he treated in a gentle, humane, and courteous manner that would be rare today, to say nothing of then. Pepi, as Goldenberg’s grandfather came to call him, eventually adopted Hansi. For the rest of his life the two men were inseparable: even after Hansi married Goldenberg’s grandmother, herself a doctor, the two ate breakfast together every morning (Pepi lived downstairs) and took vacations together. In the original German the book is called Versteckte Jahre: Der Mann, der meinen Großvater rettet (Hidden Years: The Man who Saved my Grandfather), which rightly captures its emphasis. Anyway, while I don’t regret reading this book, I note that until I sat down to write this review I’d forgotten all about it.

Flynn Berry, Northern Spy (2021)

The wider political backdrop of the novel—set in Northern Ireland at an unspecified time that seems like it could be just before the Good Friday agreement, but which also can’t be (technology doesn’t match up, for example)—gives Berry’s new novel extra heft. Impressively, she does this without any bloat. I just love how short her books are. She’s such an efficient writer.

In Northern Spy—turns out this is also a kind of apple, fitting for a book which shows the domestic and the political to be so entwined—Tessa, a BBC producer just back from maternity leave, is shocked when she sees her sister in footage from the latest IRA attack (a gas station hold up). She’s floored by this revelation, of course, but things prove to be even more complicated. Before long, Tessa is volunteering to infiltrate the IRA. In a tense interrogation, she is asked by the man she will report to why she wants to become an IRA informer. Tessa experiences no cognitive dissonance in the moment:

This isn’t so difficult. I’m a woman, after all, so I’ve had a lifetime of practice guessing what a man wants me to say, or be.

Berry’s smart and engrossing thrillers are among my favourite discoveries of the year.

Robin Stevens, Murder is Bad Manners (UK title: Murder Most Unladylike) (2014)

British boarding school crime fiction written for middle-grade readers but with wide appeal. I bought this for my daughter a few years ago when I read about it in the TLS (their irregular children’s column is excellent; I hope the new editor won’t get rid of it). Something made her pull it off the shelf last month and she immediately got stuck into it. Then she raced through the other four titles available in the US. While we waited for the others to arrive from the UK we decided to read them together, aloud. And they are a delight: suspenseful in themselves, though not too scary (even as they are thoughtful about the toll that even playacting as a detective could take) but with plenty of nods to Golden Age sleuthing that older readers are likely to enjoy. Set in the 1930s at a school called Deepdean, the books are narrated by Hazel Wong, who at the time of the first volume is newly arrived in England from her home in Hong Kong. Hazel plays Watson to Daisy Wells, the book’s beautiful, brainy, incorrigible Sherlock and self-appointed President of the Wells & Wong Detective Society.

After earning their stripes in dull but useful cases like The Case of Lavinia’s Missing Tie (Clementine took it in revenge for Lavinia hitting her during lacrosse practice, after Clementine said Lavinia came from a Broken Home), the girls take on a crime of a much greater magnitude when Hazel stumbles on the dead body of a teacher—a body that disappears in the time it takes her to find help. The headmistress thinks nothing is amiss because she finds a resignation letter from the teacher on her desk the next morning. But Wells & Wong know better. And things soon get pretty hairy. Will they solve the case before the killer strikes again?

Hazel is much smarter than Watson and Daisy less unerring than Sherlock. Which makes the books often funny, but also moving, especially in their depiction of a friendship between a popular girl who seems to have everything together and a shy one who seems to be a bit hopeless. Each needs the other—for me, the books are about shared vulnerability—and I’m looking forward to seeing how Stevens develops their story.

Ruth Rendell, One Across, Two Down (1971)

Someone on Twitter put this on their highlights of 2020 list—please remind me who you are—and I was intrigued enough to check out a copy from the library. At which point it sat around the bedroom for months until, at a time when I was supposed to be reading something else, I realized I absolutely could not live another minute without taking it up. And I was glad I did: it’s an impressive book.

Vera lives with her layabout husband, Stanley, and nagging mother, Maud. Stanley and Maud hate each other and make poor Vera’s life even worse with their endless arguments. But when Stanley learns that Maud has socked away a lot of money and plans to leave it all to Vera, he swaps her stroke medication with saccharine pills, just to see if he can hurry the process along. Pretty soon, though, events escalate, in ways he never expected. Although technically not responsible for the old woman’s death—I won’t give away the details here—in all the ways that count he’s absolutely responsible. Most of the novel is about how he gets found out. Stanley’s awful; spending time with him is not pleasant. But Vera gets a surprisingly happy ending, so the book isn’t entirely grim. Along the way, Rendell asks us to think about what draws readers to crime fiction. Is it any different from the many seemingly harmless but ultimately consuming obsessions—like the crossword puzzles Stanley wants not only to solve but to set—that litter the book? Lots going on here, in unfussy but quality prose. If One Across, Two Down is anything to go by, early Rendell is the real deal.

Becky Chambers, To Be Taught, If Fortunate (2019)

Standalone novella in the Wayfarers series, which I have not read but definitely will, as soon as my library holds come in. Recommended to me by a brilliant former student now in graduate school who has just taken a course on science fiction. Someone online described Chambers’s books as sf cozies, which makes sense to me. Some might take this as criticism, and maybe that’s how it was meant, but what I liked most about To Be Taught, If Fortunate is its fundamental kindness. This is a book fascinated by otherness and worried about how vulnerable it is to even well-intentioned encounters.

In 2045, four astronauts are sent to explore the life forms—some quite minimal, all hard for us to fathom, all valuable in their own right—on the moons of a distant planet. At some point in their exploration—and because of the distances involved, time is passing much more slowly for them than it is back home: taking on the mission means that none of them will see their families again—they realize that they aren’t getting messages from earth anymore. A companion mission, sent elsewhere in the galaxy, confirms that they too have lost contact. Should they try to return to what might be a destroyed home, or continue on, knowing that once they do there’s no going back?

The descriptions of the alien lifeforms are fantastic. I really thought this was a wise book. The only sour note is a coda referencing the title. The phrase comes from a welcome speech made by then-UN Secretary Kurt Waldheim and placed on board the Voyager spacecraft. If you’re going to mention Waldheim in a book about respecting difference, you should mention his Nazi past.

Jacqueline Winspear, The Consequences of Fear (2021)

I have to stop reading these. The circle of recurring characters has become so wide that keeping up with them means the crimes (never Winspear’s strength, or, to be fair, interest) are solved much too offhandedly. For whatever reason, the thing about the series that first drew me to it—its investigation of responsibility—just irritated me this time. I could see what Winspear was doing with the concept of fear—asking whether our duty to a nation is enough to make us repress our feelings; wondering if personal responsibilities outweigh political demands—but I couldn’t bring myself to care. Maybe because I saw the novel’s depiction of WWII as the product of philosophical liberalism, which I was feeling frustrated by because I was just coming to end of reading…

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951, revised 1958)

I spent a lot of time this month with Arendt’s quasi-history, quasi-philosophy of totalitarianism. It’s long and hard. I was sometimes frustrated by Arendt—she’s from a different philosophical tradition than the one I was trained in; she’s completely uninterested in psychology, which is baffling to me; our thinking isn’t the most sympatico—but I was often amazed. In the end, this was such a rewarding reading experience.

Which I would not have had if I hadn’t signed up for a course offered through the Brooklyn Institute of Social Research, taught by Samantha Rose Hill, who teaches at several schools in the New York area, runs a center for Arendt Studies at Bard, and has a book about Arendt coming out this summer. (Her recent Five Books interview on Arendt is exemplary.) The ideal teacher, in other words, and she taught us a lot. I enjoyed being in a class again, although I noted that some of the same anxieties that plagued me in college and graduate school resurfaced. I still fear the things I have to say are beside the point and unhelpful—but I’m not as shy anymore and say them anyway.

But what’s important here are the ideas, not my reading experience. In nearly 500 small-font pages, Arendt unfolds a sweeping argument about the connection between antisemitism, imperialism, and totalitarianism.

Alas, I don’t fully understand Arendt’s take on antisemitism. I had to miss most of the class in which we discussed this—fittingly (?) to run a Holocaust memorial program—and I haven’t finished the section. But a key idea is that, counterintuitively, Jews thrived in Europe as long as nations did. (Well, thrived, I don’t know about that, and the Jews Arendt talks about comprised a thin stratum of rich, Western European Jews. Of the Jews in Eastern Europe and the Pale of Settlement, i.e., almost all European Jews, she has little to say: Arendt was always what the Israelis call a Yekke.) The cosmopolitanism of Jews, so often held against them, and forced upon them by the fate of their diaspora, paradoxically enabled them to flourish as bankers to nation states. But when nations were replaced with Empires, specifically in the 19th Century, that relationship failed. Jews were then taken to have privilege tethered to neither role nor responsibility, earning them even greater enmity. They were left to become either parvenu (upstarts who try to fit in everywhere) or pariahs (those defiant rejects who don’t fit in anywhere). Arendt is sympathetic but disdainful to the parvenu, and fascinated by the pariah.

Both positions are responses to statelessness, an affliction that Jews especially in the 1930s but that others too throughout the 20th century experienced as the nation state came under crisis. Moreover, as Jews had been granted equality over the course of the 19th century, they proved that otherness persisted despite putative equality. (They were equal under the law but they maintained their traditions and beliefs.) Because the nation state—government by consent—is predicated on homogeneity, it responds poorly to pluralism. As pluralism increased in the 19th century, nations responded by looking beyond their borders. The result is modern imperialism, which is not the integrated pluralism of Rome but a fractious destabilized agglomeration that eventually turns on itself.

Modern imperialism mostly took place overseas (Africa, the Middle East.) It occurred as a combined political and economic crisis. After centuries of increasing economic power, the bourgeoisie finally wanted political power as well. In a brilliant reading, Arendt says that the bourgeoisie found its philosophical underpinning in the ideas of Hobbes (or, put differently, that Hobbes had prophesized the bourgeoisie). In Hobbes’s “war of all against all” the only possible “philosophy” is individual growth, resulting eventually in tyranny. The bourgeois worldview is fundamentally destructive, because fundamentally acquisitive. It believes only in endless growth: more has to become more. (Sound familiar?) Overseas imperialism allowed this antihumanist thinking to flourish, at least temporarily, and at the cost of great suffering and destruction to the local or “native” people. (Which Arendt is frankly pretty uninterested in.) The imperialist encounter with non-European others led to the development of racism from what had previously been race thinking. That is, individual instances of prejudice became turned into an ideology. Race became weaponized by the state as a form of violence. (Racism is totalized race thinking.) As an ideology, racism must be understood as necessary/inevitable, not like race thinking, which was the result of individual instances of prejudice, bias, or domination.

When the domination of racism combined with the inherently metastatic avarice of imperialist capitalism, an inherently unstable contradiction arose. (We think the world is infinite, but its resources are finite—we live every day the dawning realization of that contradiction—this is the kind of instability Arendt has in mind.) Eventually the instability of racist imperialism, which had been a kind of safety valve for the European nation (now Empire), bounced back, such that the tactics of violence, oppression, and power previously used overseas were perpetrated on civilians in the homeland. (The power of police and paramilitary forces rose greatly in this period.) Unlike nations, empires are no longer organized around classes—that structure collapses, and along with it the primary way we have developed of organizing people so that individuals feel they belong and find meaning. The loss of this meaning is, Arendt warns, very bad. With it the distinction between public and private life that is the foundation of freedom vanishes. Those realms are replaced by what Arendt calls “the social,” which is an atomized levelling: no more classes, only masses. The masses are desperate to regain the meaningful experience they have been cut off from. Enter totalitarianism. Totalitarian regimes work on people who have no meaning. Totalitarianism—the governmental form of imperialism—is what happens when expansionism takes political form. The belief in endless growth, avarice, accumulation is turned to conquering and subordinating every subject of the regime.

As far as Arendt is concerned, from her vantage point in the 1950s, there have only ever been two totalitarian regimes: Nazi Germany (from its inception, perhaps, but certainly from 1935 – 45) and Stalinist Russia (from about 1930 to Stalin’s death). Totalitarianism is not, for her, a synonym for autocracy, tyranny, or even dictatorship. Totalitarian regimes are barely regimes at all: they are movements. Neither nation nor empire is their real focus. Instead they focus on the party. Nazism and Stalinist Communism are at stake, not the Reich or the USSR. When a totalitarianism movement comes to power, they do everything they can to change reality. The ideologies animating totalitarian movements are about what will be, not what is. Totalitarian movements promise a future but they are not in fact interested in attaining it. Or, rather, their philosophy of aggression and accumulation, their inexorable drive to dominate, means that they cannot in fact countenance any final or complete end.

An important consequence of this mindset is that the enemies of the movement are never final. Strikingly, Arendt argues that the Jews, although the primary victims of the way Nazism played out, were not the Nazis’ sole or even primary enemy. It’s true that, historically, Jews were not the first victims: those were communists and socialists and, importantly, the mentally and physically disabled: the latter was the first group singled out for being killed tout court. The refusal of ordinary citizens to accept this state of affairs meant that the party delayed the plan, but they never shelved it. And there were definite plans to exterminate what the Nazis called “the Slavs” after they conquered Russia and finished with the Jews. (A genocide they began in Poland in 1940.) Arendt also points to memoranda and bits in Mein Kampf where bureaucrats and Hitler muse about eliminating people with various incurable illnesses, or even predilections toward them, like cancer. Arendt’s point is that regardless of what the Party says publicly there will always be more victims. It is in the nature of totalitarianism to find them.

In doing so, totalitarianism relies on a belief in secret meanings. That is how it begins to change reality. What you see is not the real truth of things. (To use one of Samantha’s examples—you think you see a pizza place in DC but really you see a front for child sexual exploitation; how much Arendt’s diagnoses pertain to the US today exercised the class a lot, but that’s a different topic.) Totalitarianism forces its adherents, and everyone who lives under it, to affirm the false. Experience, under totalitarianism, only affirms ideology. It has no meaning in itself. The result: thinking is replaced by thought (the already known, the prepackaged, the tidy explanations of ideology). For Arendt, that is one of the worst things that can happen to human beings. (Note, by the way, that those who wield thought can be smart, and they’re not cynical either (which is terrifying, IMO). But they are incapable of thinking. Which, it seems to me, means that for Arendt they are barely human.

It’s all fascinating, and quite compelling. For me, Arendt fails to consider how power creates as much as represses. (She is not Foucault). That is, she fails to account for the meaning people find in even hateful or oppressive thinking. She also ignores the effort totalitarian movements put into creating a community of believers. (There’s nothing in her book about, say, the Hitler Youth or the Bund deutscher Mädel or the Kraft durch Freude vacations or any of the myriad ways Nazism, to take only the example I know best, created the Volksgemeinschaft (the community of the people).

Plus, Arendt’s understanding of the camp system comes too much from the model of Buchenwald (and to some extent Auschwitz). No surprise, given her background and sources, and the reality of what she was able to read in the late 40s and early 50s. And her knowledge is impressively nuanced for the time. But she is led astray, in my opinion, by relying so heavily on the work of David Rousset, whose fascinating book about his time in Buchenwald I want someone to reissue in English ASAP, but whose experience as a communist prisoner in that particular camp (there was strong communist leadership, even a kind of resistance movement, in Buchenwald) is anomalous in comparison to the general KZ experience.

Anyway, as Samantha put it, Arendt asks key questions. Is there a way of thinking that’s not tyrannical? How can we protect spaces of freedom? How can we live under something other than imperialism or totalitarianism? These remain resonant, indeed urgent. The Origins of Totalitarianism gave me so much to think about; I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to read it closely.

Charles Portis, True Grit (1968)

I wanted to spend my birthday with some good light reading, so I chose three possible contenders from my massive TBR pile and put up a Twitter poll to help me decide where to start. Portis’s novel about a teenager avenging her father’s death in Reconstruction-era Arkansas and the Indian Territory of Oklahoma won by a landslide. And the people knew what they were talking about! True Grit is a delight, often laugh-out-loud funny. I would have loved it even more had I not seen the movie (the Coen Brothers version), as some of the best jokes and the plot came back to me as I read. But the film can only approximate the novel’s primary pleasure: Portis’s masterful use of voice, evident in both Mattie’s narration and the characters’ conversations. (This is not a Western about strong, silent types: nobody ever shuts up.) An added pleasure was reading about Arkansas locations (and types) I know; I noticed that some of the bit characters even had last names I recognized from living and teaching here.

I suspect that a second reading—which the novel definitely merits—would give me a lot more to think about. But even on a relaxed first reading I recognized that much of what makes the book so interesting comes from the difference between the time of the telling and the time of the events. Mattie is fourteen when she sets out to find Frank Chaney, but an old woman when she tells us about it. In part it explains, or makes us wonder about, Mattie’s engaging but puzzling mixture of naivete and pursed-lipped moral certainty. Is that the difference between the girl and the old woman, or did she always combine these contrary aspects? The disparity between past and present is especially evident in a final scene at a traveling fair in 1920s Memphis: the “wild west” of the novel’s main action has become fully commodified. But was it ever any different? After all, the novel’s many crimes are prompted by money, even if they hide under the veil of honour. Too many guns, too much economic inequality: in this sense, True Grit still rings painfully true.

Let me quote a couple of choice bits, just because.

Here’s Rooster Cogburn, the one-eyed US Marshall Mattie hires to help her find Chaney, complaining about paperwork:

If you don’t have no schooling you are up against it in this country, sis. That is the way of it. No sir, that man has no chance any more. No matter if he has got sand in his craw, others will push him aside, little thin fellows that have won spelling bees back home. [Little thin fellows! Much funnier than “thin little fellows.”]

Here’s Rooster, on first meeting a Texas Ranger named LaBoeuf who is also on Chaney’s trail of, learning that there’s a bounty out on the man because he’s also shot a Texas senator:

“Anyhow, it sounds queer. Five hundred dollars is mighty little for a man that killed a senator.”

“Bibbs was a little senator,” said LaBoeuf. “They would not have put up anything except it would look bad.”

And here’s Rooster telling about the time he ran an eating place called The Green Frog, but had to give it up after his wife left him:

“I tried to run it myself for a while but I couldn’t keep good help and I never did learn how to buy meat. I didn’t know what I was doing. I was like a man fighting bees.”

Fighting bees. Perfect. Reading True Grit is the opposite of fighting bees. Easy, full of sweet and honey.

So that was a pretty damn good month. Arendt: titanic. Abad: deeply satisfying. Portis: such fun. Rendell and Berry: old and new masters of suspense. The Karmel sisters: what have you done to my heart?