Today‘s reflection on a year in reading is by Victoria Stewart (@verbivorial). Victoria is a university lecturer in English literature, with special interests in Holocaust writing and interwar detective fiction (she’s like me, only more successful), but this post focuses on some of what she read for pleasure in 2021.

Look for more reflections from a wonderful assortment of readers every day this week. Remember, you can always add your thoughts to the mix. Just let me know, either in the comments or on Twitter (@ds228).

Reading Maria Stepanova’s The Memory of Memory,translated by Sasha Dugdale, I wasn’t sure whether to be gratified or not to recognise myself as this ‘type of person’:

Notebooks are an essential daily activity for a certain type of person, loose-woven mesh on which they hang their clinging faith in reality and its continuing nature. Such texts have only one reader in mind, but this reader is utterly implicated. Break open a notebook at any point and be reminded of your own reality, because a notebook is a series of proofs that life had continuity and history and (this is most important) that any point in your own past is still within your reach.

In any case, my ‘reading notebook’ came in useful, or finally justified its existence, when Dorian kindly invited me to write this post. Looking through the list of what I read in 2021, I see that what might broadly be called ‘autofiction’ figured quite heavily. I’ve always been drawn to realist fiction, and the idea of writing a novel that could be mistaken for a factual text is one logical extension of that, I suppose. Whether The Memory of Memory, an exploration of Russian/Soviet family history, steps over the line from fiction into essay maybe only Stepanova herself can tell, though for me it demanded the kind of attention that I associate with reading nonfiction.

I started 2021 by re-reading Emmanual Carrère’s The Adversary, translated by Linda Coverdale, an account of an act of criminal deception that formed the basis for the 2002 film of the same name [Ed. – I believe it also inspired Laurent Cantet’s excellent Time Out (L’Emploi du Temps), 2001], but which, like many classic true-crime texts, weaves the story of the author’s ‘investigation’ into their account of the crime. I must have first read this soon after it was published in the early 2000s, and only belatedly realised that Carrère was the author of Limonov, translated by John Lambert, an experiment in biography that’s also intertwined with autofictional elements. I read for the first time Carrère’s nasty, brutish and short Class Trip, translated by Linda Coverdale, which, told from a child’s perspective, forms a sort of distorted mirror image of The Adversary. My Life as a Russian Novel, another Coverdale translation, is probably the one I’d be least inclined to return to. [Ed. – Of course that’s the one I own…] The story of Carrère’s quest to find out about his grandfather, who was (probably) executed at the end of the Second World War as a collaborator, gets submerged under other strands that, to me, were less engaging.

I’d resisted reading both Tove Ditlevsen’s trilogy, Childhood, Youth, Dependency, translated by Michael Favala Goldman, and Vigdis Hjorth’s Will and Testament, translated by Charlotte Barslund, as I’m not generally keen on texts dealing with traumatic childhoods or addiction, but I was glad that recommendations from other readers persuaded me to get over that resistance. The first two volumes of Ditlevsen have a black humour that I hadn’t expected, though I found Dependency much tougher, and Hjorth’s reflections on family dynamics and being a grown-up child struck a chord:

Sybille Bedford writes somewhere that when you’re young you don’t feel that you’re a part of the whole, of the fundamental premise for humanity, that when you’re young you try out lots of things because life is just a rehearsal, an exercise to be put right when the curtain finally goes up. And then one day you realise that the curtain was up all along. That it was the actual performance.

During the pandemic lockdown, which went on for an extended period in the part of the UK where I was living in 2020-21, I probably did more re-reading than I had previously: more time at home led me to scan the bookshelves and, in some cases, acknowledge that I could remember very little about volumes had been sitting on my shelves since being bought and read maybe twenty years ago. Sometimes that re-reading turned up forgotten gems (like Elke Schmitter’s creepy Mrs Sartoris, translated by Carol Brown Janeway). On other occasions, I didn’t get past the first page, and the local charity shops got the benefit when they eventually re-opened. I’m not sure what prompted me to start re-reading Alan Hollinghurst’s novels in 2021, but I’m glad I did. I went more or less in order of publication, and I particularly enjoyed the leaps in time that structure his later novels, especially The Stranger’s Child and The Sparsholt Affair, the brief disorientation that comes from figuring out how the protagonists in the current section relate to those of the previous one.

Another author I binged on, though I think with one or two exceptions I was reading his novels for the first time, was Brian Moore, whose centenary fell in 2021. [Ed. – So good!] Born in Belfast, Moore relocated first to Canada and then to the USA as an adult. I enjoyed the awful embarrassment of school-teacher Dev’s attempt at courtship in the Belfast-set The Feast of Lupercal. That novel was published in 1958, prior to the launch of the IRA campaign which forms the backdrop for Lies of Silence. Though the politics are much more explicit here, as in Lupercal matters of political choice can’t be separated from apparently more personal ethical and moral decisions. The Doctor’s Wife, about a married woman’s relationship with a younger man, has aged less well, andMoore’s non-fiction novel The Revolution Script didn’t quite work for me, though it did bring into focus a moment in Canadian history of which I knew very little, the ‘October Crisis’. [Ed. – That was a big deal, all right. Curious about this now.]

Several other novels I read this year also took the tropes of the thriller and gave them an interesting twist. Chris Power’s A Lonely Man places Robert, its Berlin-based author protagonist, in a moral dilemma after he becomes entangled with Jonathan, a ghostwriter. Ben, the narrator of Kevin Power’s White City (the two Powers aren’t related) has a voice that one reviewer found reminiscent of Martin Amis’s early work. Perhaps they were thinking of Ben’s reflections on abandoning his PhD on James Joyce:

Now I regarded my old underlined Penguin Popular Classics copy of A Portrait as a kind of embarrassing ex-girlfriend to whom I was still attracted but with whom things had not really worked out. [Ed. – Hmm…]

But the payoff is serious, and the switch in tone subtle. I heard about Katie Kitamura’s A Separation via reviews of her most recent novel Intimacies. Like Chris Power’s novel, A Separation uses a disappearance to open up to view a disintegrating relationship. The action of Kitamura’s novel takes place on a Greek island; Alison Moore’s The Retreat has an invented island off the coast of England as the setting for what becomes a nightmarish artists’ retreat, its interlocking narratives connecting in ways that reveal the whole narrative to be as carefully constructed as a piece of origami.

I don’t generally read much science fiction or speculative fiction, but Isabel Wohl’s Cold New Climate, goes stealthily in that direction. Lydia is shocked when, after what she intended as a temporary break from her older lover, she returns to find he is ending their relationship. Her reaction seems designed to be self-destructive and to inflict the maximum amount of pain on those around her, but the ending confronts the reader with destruction of a different kind. [Ed. – Anyone know if this is getting US release?] Rosa Rankin-Gee’s Dreamland was an all-too believable dystopia that conveyed the urgency of its political concerns without ever becoming shrill. M. John Harrison’s The Sunken Land begins to Rise Again intertwines the stories of former lovers Shaw and Victoria, moving between Shaw’s life in London and Victoria’s relocation to a house she’s inherited in Shropshire. Victoria’s new neighbours are not quite what they seem, and the watery theme manifests itself in ways that veer between the fairy tale and the horror story.

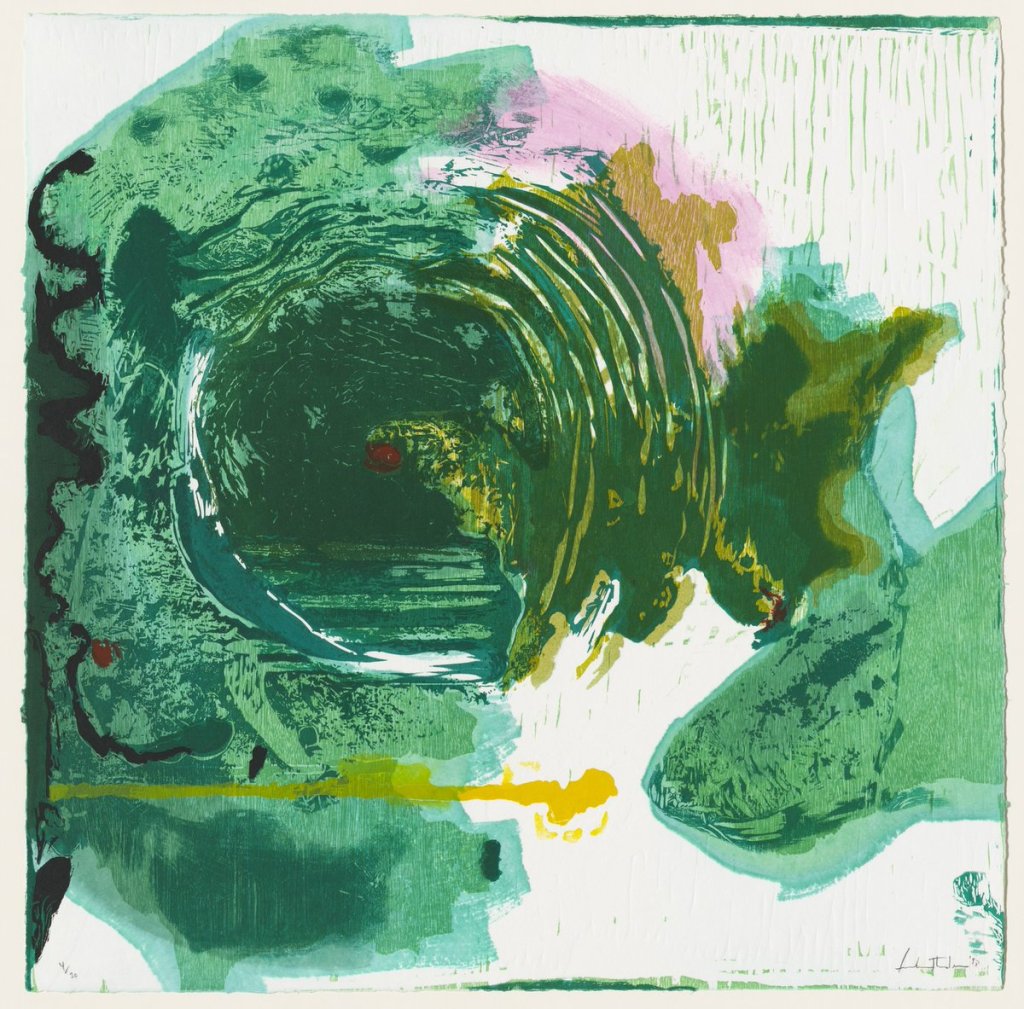

Where non-fiction is concerned, it was mainly artists’ biographies that caught my eye in 2021, maybe because visiting exhibitions was more challenging than usual. Andy Friend’s biography of John Nash was so beautifully illustrated it almost made up for not being able to get to the exhibition at Compton Verney in Warwickshire that prompted it. Friend’s handling of the death of Nash’s son was especially sensitive. I was lucky enough to see a small exhibition of John Craxton’s work at the Fitzwilliam in Cambridge in 2013, and Ian Collins’s biography was another gorgeous volume, benefitting from the author’s personal connection with the long-lived Craxton. And Jenny Uglow’s Sybil and Cyril was a dual biography of the unusual artistic partnership between Sybil Andrews and Cyril Power that gave a new slant on mid-twentieth century commercial art: among much else, they designed a number of posters for the London Underground.

Next up, I’m waiting for an excuse to treat myself to Alex Danchev’s biography of Rene Magritte, and Tessa Hadley’s new novel Free Love is high on my list for 2022. [Ed. – Just finished it this morning, and it is terrific.]