At the beginning of A House of Dynamite, Kathryn Bigelow’s new film, now in theaters and on Netflix, an intercontinental ballistic missile shows up on the radar screens of a tracking station in Alaska. Is it a test? A malfunction? If, as it soon becomes clear, it’s real, who launched it? These questions are picked up by the team at the White House that monitors threats to the country. Soon the military command, the Department of Defense, FEMA, and other agencies are involved. They have less than twenty minutes to shoot the missile down before the ten million people in and around Chicago are incinerated. When the ground-based interceptors fail, a decision falls to the President (Idris Elba, known to the audience only as a voice until the last third of the film). Should he order a retaliatory strike (and if so, against whom)? Perhaps unsurprisingly, given its love of expertise, the film presents the President as a mediocrity doing his best but outmatched by the enormity of the situation.

The movie drives hard and fast. It’s suspenseful and frightening. But its real interest is in something seemingly much less exciting: expertise. On one level, A House of Dynamite is a paean to experts, people with specialized knowledge that guides informed yet decisive action. In the current moment our American oligarchic and fascistic kleptocracy, the days of the experts often seems to be over, a victim of a long-running war against education, perpetrated by privileged people who have benefitted from it. How thrilling, then, to see Captain Olivia Walker (Rebecca Ferguson), Deputy National Security Advisor Jake Bearington (Gabriel Basso), or even General Anthony Brady (Tracy Letts, he of recent Criterion Closet fame: “take your dissonance like a man) assert the value of reasoned protocol. Following procedure never seemed so exciting.

On another level, though, the film shows nothing but the failure of expertise. Characters struggle to communicate with each other, often in the most banal ways: someone important is out of the office; phone calls break up; conflicting video conferencing systems can’t be patched together. And they fail to see eye-to-eye. As their confidence in the country’s preparedness fades with every minute, they argue over the merits of a counterstrike. Will it stop further attacks? Or bring about the end of the world?

How does the film’s form relate to this content? To what extent is it an example of expertise? It’s certainly professional. A House of Dynamite moves quickly, even neatly, shifting between locations and institutions without ever leaving the audience confused. This clarity is the more impressive in that Bigelow has split the film into three chapters. Each tells the same story, but highlights different characters. There are a lot of off-screen voices in this film—people on conference calls, crackling out of microphones. We get the pleasure of putting faces to those names as we revisit earlier scenes from different perspectives.

Despite its looping, non-linear telling—a counterpoint to the relentless ticking of the clocks down to zero and annihilation—A House of Dynamite is efficient to a fault, offering minimum requisite humanizing beats to its characters. These moments often involve children. Captain Walker takes her son’s plastic dinosaur to work after he solemnly presents it to her on her way out the door; later she winces when slipping on her heels after passing through security outside her office before pausing, stork-like, to dig out the offending figurine which has must have fallen into a shoe when both were in her bag. A fighter pilot stationed in the Pacific stuffs the teddy bear he’s bought for his kid into his locker, only to fail to notice that it slides to the floor when his attention is distracted by the alarm that indicates a sudden mission. This tendency to use children as signifiers of the personal reaches its height when the Secretary of Defense (Jared Harris) kills himself after realizing that he will be unable to save his daughter, who lives in Chicago.

These decisions are mawkish (though the man’s last call with his daughter is affecting: he understandably sees no reason to tell her she is likely to die within minutes). But that’s not the problem. The problem is how calculating the film is in humanizing its characters, how minimal and cliché its sense of what the human means. I found this especially disheartening in a movie that claims to abhor the destruction of human life.

In terms of its form, well, there’s professional, and then there’s polished. In trying to depict what stands to be lost in the event of the unthinkable, A House of Dynamite is as instrumental as the failed way of thinking that reduces weighty decisions to options in an if-then chart. Hard to imagine a less shaggy movie. (No “few small beers” here.) I was left wishing for some loose ends.

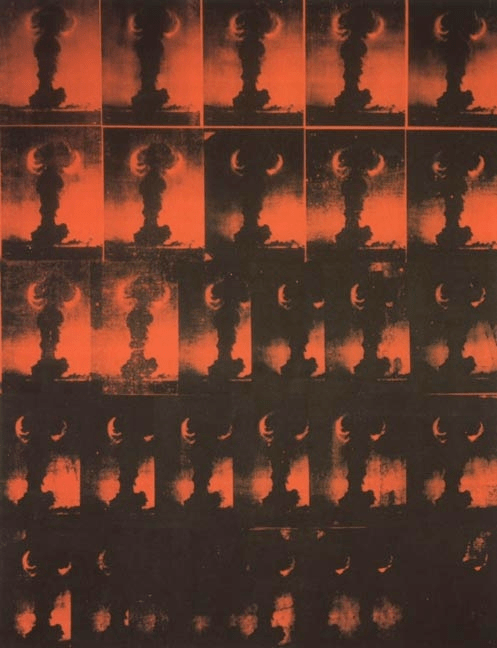

That might seem crazy given that probably soon-to-be notorious open ending. We never learn what the President decides to do. Or if Chicago is obliterated (though it sure seems likely). Or We if the repeated claim that “sometimes these weapons malfunction or don’t detonate” is wishful thinking. Sitting in the theater, I felt a brief flare of frustration. But how is a film like this supposed to end? After all, it argues that building a house full of dynamite and then deciding to keep living in it is insane. To that end, the missile must remain anonymous, its source forever unknown. The Russians deny it. The Chinese deny it. The North Koreans are unreachable. Ana Park (Greta Lee), the expert on that country, lays out a convincing scenario in which the North Koreans might be motivated to launch a suicide attack. But nobody knows. The film argues that it doesn’t matter. The possibility of unmotivated mass destruction is simply built into a world with nuclear weapons.

This choice on the film’s part, however, means that politics is off the table. Despite a good scene in which the Deputy National Security Advisor has a tense, heartfelt, but ultimately inconclusive phone call with a Russian counterpart, geopolitical maneuvering or negotiating are rendered inoperative by the bomb’s anonymity. The attempt to game out—in less than twenty minutes—possible consequences of preemptively launching a return strike, or of choosing not to, turns into abstraction, a kind of amplified trolley problem that the film doesn’t have the chops or stomach to develop. (Clearly, though, the tough-minded hawk, sitting in a bunker somewhere in the South Pacific, isn’t to be trusted. He puts eight sugars in his enormous travel mug of coffee.) I’m not sure what Bigelow had in mind by putting the North Korea expert, who fields calls from frightened officials on her day off, at a reenactment of the Battle of Gettysburg with her pre-teen son. Is the idea that the Civil War was as senseless as a nuclear attack? Or, on the contrary, that however terrible that war, it was at least a fight with dignity, valor, etc.? Or that any terrible event will eventually be subsumed into nostalgia and/or the politics of commemoration?

I said before that this is a frightening movie. It induces feelings of panic, helplessness, sorrow, and rage. And that, more than any mourning of the utopia of expertise, makes A House of Dynamite a movie for America in 2025.

But only in the worst, paralyzing way. Admittedly, paralysis constitutes much of what I at least experience most often these days. But that’s not the only way we can respond just now. And not the one that we need to emphasize if we are going to change the mess we’re in rather than just experience it. What would this film be like if it valued thinking more than the compartmentalization of calm professionalism and abject terror?

What if Bigelow or her writer Noah Oppenheim had read Elaine Scarry’s Thinking in an Emergency (2011)? There Scarry argues that America has dangerously normalized the idea of emergency as exception, and therefore as something that requires citizens to set aside democratic participation for unchecked executive action. She offers examples from around the world where careful but decentralized emergency preparedness results in mutual aid among citizens, not force from the State.

The protocols devised in the US to respond to nuclear attack—the nuclear codes; the handbook with its menu of increasingly drastic responses; the double-checking of identities; the sequestering of the chain of command, hell, the very idea of a chain of command—are designed to protect a few when the many die a terrible death. The film’s last scene shows buses of officials designated as indispensable arriving at a bunker in the Pennsylvania countryside. (It’s clear that what matters is position, not person: thus the inclusion in the film of a FEMA employee based in Chicago (Moses Ingram), responsible for disaster response; the woman has only been in the job a short time; her colleagues are actively hostile when they realize that she, not they, will be sent to supposed safety.) We get no sense of what will happen to those individuals should that bomb in fact land. The protocols of response to a nuclear attack, like the film that shows them to us, is governed by ruthlessness. The only challenge to that brute instrumentality—and the only thing that could count as a loose end in the movie—is that Park, the North Korea expert, stumbles off the bus with her son. It’s a hint of human possibility in this fascinating but inhuman film..