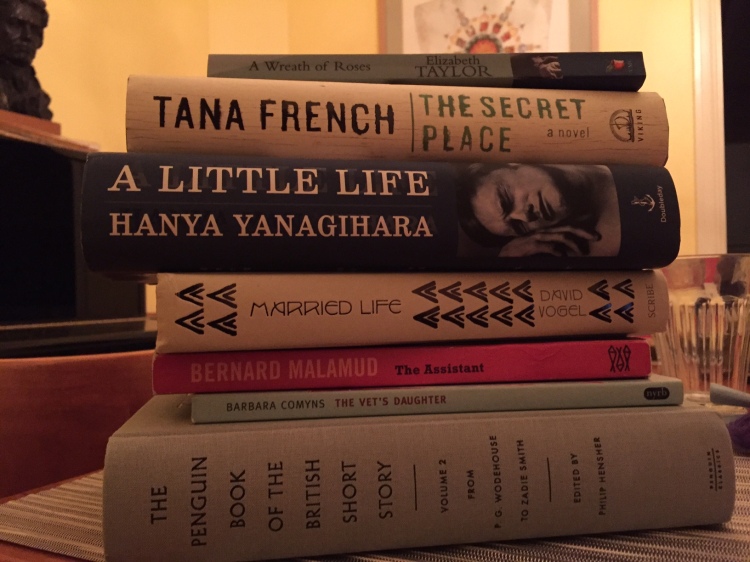

2015 was a good year in reading. Better than 2014, though nowhere near the annus mirabilis of 2013 (pre-blog, alas). I read 80+ books. Here are the ones that most stayed with me:

A Little Life—Hanya Yanigahara

The reading event of the year for me. Everyone has an opinion about it, and they’re mostly strong opinions. I understand the main objections—it’s too long, it’s indulgent, it gets off on abusing its main character and even maybe its readers, its prose is sometimes clunky, even embarrassing—but I don’t feel them. These days I struggle to keep my attention away from my phone, social media, hockey scores, you name it. Sometimes I worry I don’t have the reading stamina I used to. In this regard, A Little Life was a gift: an intense, immersive reading experience that captivated me not just for the week of the reading but throughout the whole year. I wrote about it here.

Married Life—David Vogel

Written in Hebrew and published in Vienna in 1930, this is an extraordinary book that expands our sense of what European modernism was all about.

If I read Hebrew, I would write Vogel’s biography. Born in the Pale of Settlement, Vogel made his way via Vilnius and a brief stint as a yeshiva student to Vienna just in time to be interned as a Russian citizen during WWI. After the war he loafed, nearly penniless, in Vienna’s cafes, finding a little translation work and writing his first poems and novellas. He immigrated briefly to Palestine in the late 20s but Zionism never held much appeal for him and he returned to Europe, eventually finding his way to Paris in the early 30s. Tragically he was interned in the next war, this time as an Austrian citizen, and was deported via the infamous transit camp at Drancy to Auschwitz where he was murdered in 1944.

In Married Life the poor but promising writer Rudolph Gurweil meets the impoverished and rapacious aristocrat Thea von Takov and falls immediately under her spell even though he’s not sure he likes her very much. The two marry after only kowing each other for a few weeks and things go badly from the start. Thea converts to Judaism to marry Gurweil but among other things she’s a terrible anti-Semite. The novel is a drawn-out depiction of a disastrous marriage, but it’s also a glorious depiction of shabby Jewish Vienna.

I started a review and got sidetracked. I’d really like to finish it. If it got this book even one more reader it would be worth it.

Heartfelt thanks to heroic translator Dalya Bilu and to Australian-based Scribe for publishing this masterpiece, not least in such a gorgeous edition.

The Vet’s Daughter—Barbara Comyns

Wonderful, heartbreaking novel about a young woman who levitates. I wrote about it at length here and my appreciation only increased when I taught it this fall. Happily, my students loved it too; I received several excellent papers about it. I’m about to write more about Comyns myself. More on that soon, I hope.

The Heat of the Day—Elizabeth Bowen

The same students who enjoyed Comyns did magnificently with this marvelous novel of the Blitz and its aftermath. The course is on Experimental 20th-Century British Fiction, and I hadn’t taught Bowen for a while (six years, in fact), after my previous attempt at teaching her failed spectacularly. I finally worked up the courage to try Heat again, and am so glad I did. It helped, of course, that this was a particularly strong group of students. It was really fun helping them work through Bowen’s famously thorny sentences. To the North might still be my favourite Bowen, but this novel about lying to one’s self and to others is one of her best. I often grumble about how teaching gets in the way of reading. But sometimes the chance to return to the same set of books is a joy. As Roland Barthes once said, those who don’t re-read are doomed to read the same text over and over again.

Bernard Malamud

Another one from the teaching files, at least in part. I taught an introductory level course on short fiction this fall. (For a while I blogged about it regularly—the first installment is here, if you’re interested—but eventually I capitulated to the semester’s demands and gave up.) The touchstone text was Malamud’s first collection, The Magic Barrel. I’d taught these marvelous stories before but it had been a while and found I liked them even more this time.

I’ve always loved their enigmatic qualities, and had long been curious whether his novels were like that too. So I read The Assistant over Thanksgiving (I started a post on that too which I also failed to complete). It tells the story of Morris Bober’s struggle to eke out a living from his small grocery store in a poor part of New York, a struggle that only deepens when he takes on a drifter as a de facto assistant. It is also one of the most depressing books I’ve ever read, with a scene that genuinely shocked me. Malamud’s stories are hardly heartwarming, but they have a lightness missing from this novel. Absolutely worth reading, though.

Various short stories

The Penguin Book of the British Short Story—Philip Hensher, Ed.

As I said, I taught a lot of short stories this fall, and in the process I remembered how much I love the form. Edith Pearlman, Katherine Mansfield, and D. H. Lawrence were particular favourites. I also want to tip my hat to this wonderful two-volume edition of short stories edited by Philip Hensher. I’ve got volume 2 (they’re only available in the UK and a bit pricey but the production values are amazing) and I’ve only read a handful of the stories. But the roster is exciting; not just the usual suspects. Hensher plowed through a ton of late-19th and early-20th century magazines and has found some amazing stuff. I especially like one by “Malachi” (Marjorie) Whitaker, called “Courage”: it’s going straight on to the Spring syllabus. Hensher’s introduction makes a fascinating case for why Britain produced such good short fiction in the years 1890-1940 and why economic and structural conditions make it unlikely for the form to flourish in the same way again (which isn’t the same as saying there are no good instances of the form today: volume 2 goes from P. G. Wodehouse to Zadie Smith). Please Penguin, bring this out in the US.

The Book of Aron—Jim Shepard

A Brief Stop on the Road from Auschwitz—Göran Rosenberg

Holocaust literature is central to my teaching, and so also to my reading. These two books impressed me this year, the first a novel of the Warsaw Ghetto that I wrote about at Open Letters Monthly and the second a second-generation memoir that I reviewed at Words without Borders.

Death of a Man—Kay Boyle

Thanks to Tyler Malone of The Scofield I learned a lot about Kay Boyle this year. The best thing I read by her was a heartbreaking early story about failed pedagogy called “Life Being the Best” (read it!), but the book I spent the most time with was this 1936 novel about an American heiress who falls in with fascist sympathizers in pre-Anschluss Austria. I can’t say I liked the book all that much, but I was utterly fascinated by it and I enjoyed wrestling with its slippery politics. You can read my essay, along with many other wonderful pieces, here.

A Wreath of Roses and Blaming—Elizabeth Taylor

These are two of the best books I read this year, but they’re wrapped up in guilt for me because I promised someone a piece about them and never delivered. (Not yet, anyway…. I still want to, though!) I’ve loved everything I’ve read by Taylor, but these are the best of the bunch. Blaming (1976), her last book, is about what happens to a middle-aged woman after the unexpected death of her husband. It manages to be both rueful and acerbic. A Wreath of Roses (1949) is a masterpiece and if it were in print in the US I would have taught it this semester for sure. Less histrionic than Bowen’s Heat of the Day but similarly a novel of what the war did to England, it’s also a story of female friendship that earns its epigraph from Woolf’s The Waves. Genuinely haunting: I read it in June and still think about it regularly.

The Secret Place—Tana French

French doesn’t need me to sing her praises. Everyone already knows she’s the best crime writer today. Some thought this latest book—for some unaccountable reason I held off reading it for almost a year—in the Dublin Murder Squad series a falling off, but I adored it. I especially loved the echoes of Josephine Tey’s Miss Pym Disposes. French is such a genius because she writes super suspenseful books that are ultimately about something quite different: they are fascinated to the point of obsession with the idea of friendship—interestingly, romance or sex features hardly at all—especially how friendship intersects with the partnership between detectives. Yet again French proves she writes vulnerable men better than anyone.

*

Other good things: Vivian Gornick’s The Odd Woman and the City is a brilliant essay-memoir and I would have written more about it here but it’s late and I’m tired (the Open Letters piece is good, though); The Hare with Amber Eyes (again, everyone already knows it’s amazing—I most liked a surprising Arkansas connection!); Emma (enjoyed re-reading this and wrote about the experience here and here); bits of Balzac (the last 100 pp of Pere Goriot, which practically had me in tears; the scene in Eugenie Grandet when Eugenie wakes at night to see her father and his servant taking his gold downstairs: hallucinatory); Wilkie Collins (I liked both The Dead Secret and The Law and the Lady). Also, good light reading: Ben Aaronovitch’s Rivers of London (urban fantasy—smart and funny: read the first two this year and mean to finish the series in 2016); Hans Olav Lahlum’s K2 books (engaging Norwegian homage to Golden Age crimes, locked room mysteries and the like); Ellis Peter’s Cadfael books (read the first: surely the beginning of a beautiful friendship).

*

Reading is a passionately solitary experience, but also a joyously communal one. That’s true (mostly) in my classroom and, increasingly, on social media and the Internet more generally. Sometimes I find the constant stream of books to read that come through my Twitter feed a little daunting, but mostly I’m thrilled to know that so much reading is going on, so vigorously and passionately.

Thanks to everyone who read this blog in 2015, especially those who encouraged me and prompted me to think harder or differently about the books. It is wonderfully strange for me to speak so much with people I haven’t for the most part even met about something so important to me.

Thanks too to those who published me this year, especially the wonderful people at Open Letters Monthly. Here’s to more writing next year, and of course to more reading.