Regular readers will know that for the last several years I’ve solicited Year in Reading reflections from friends and trusted readers. As we’re well into February, I’ve scaled the project back considerably this time, but I’ve got some good stuff coming your way over the next few days. Today’s installment, her fifth, is by Hope Coulter, my friend and former colleague. Hope is a writer in Little Rock.

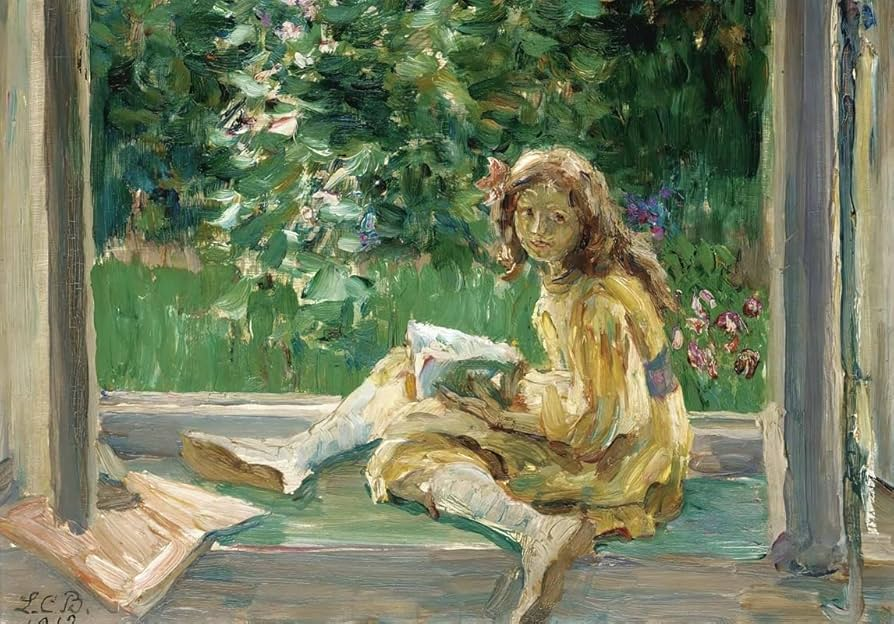

Like Dorian, I retired from Hendrix College last May. One of the joys of retirement has been more time to read. With more free hours in the day and no class prep I’ve been able to read gluttonously, leisurely-ly, reminding me of how I read as a child in our long low house on the bayou—stretched out for hours at a time with a book, changing position whenever a propping arm got tired. Once, I remember, I was performing the cliché of reading late into the night with a flashlight under the covers (I’m not sure where I even got this idea) when my father walked in and flipped on the light. “What in the world are you doing? We don’t mind if you stay up and read, but for heaven’s sake don’t strain your eyes.” [Ed. – Good Dad.] My body is bigger and creakier now, but the sense of abandon, of decadent pleasure in reading, is much the same.

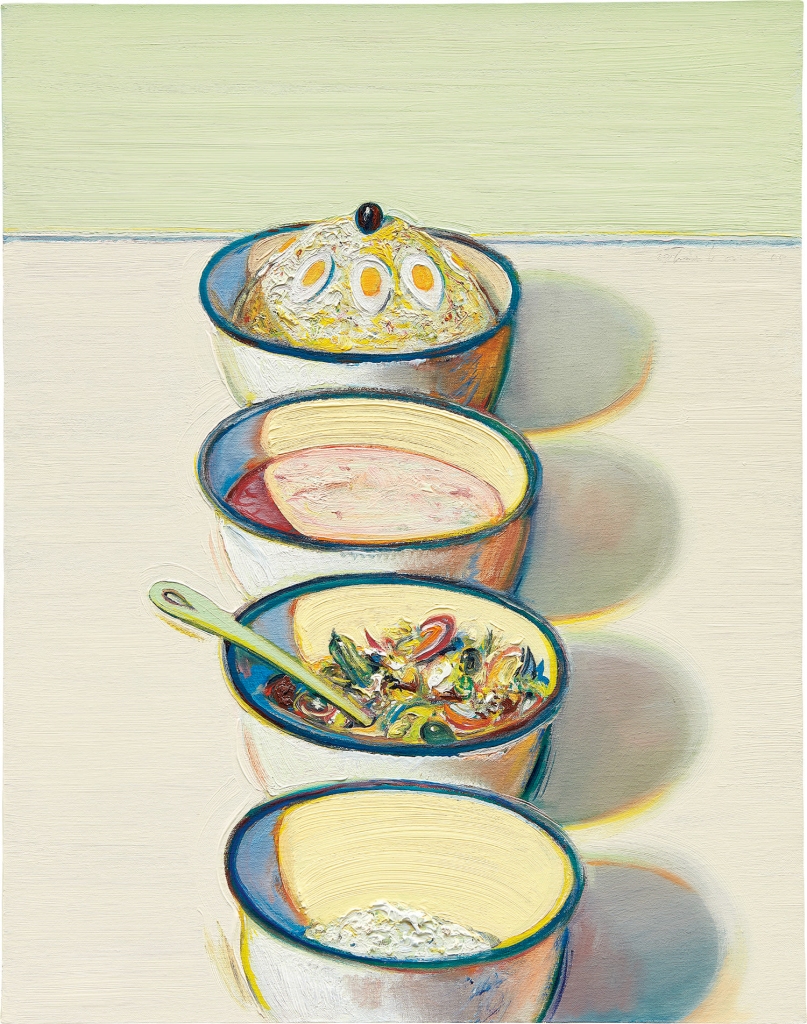

In 2025 a third of the books I read happened to be memoirs, and of these, as I followed my nose and my algorithms, one-third were by chefs, restaurateurs, or gastronomes [Ed. – gastrognomes, you say???]. My favorites are as good a way as any to start off this list.

Best food-related memoirs:

- Most Likely To Make You Hungry, Make You Laugh, and Make You Want To Cook: Stanley Tucci, Taste: My Life Through Food and What I Ate in One Year (and related thoughts) – Pure delight. I love this guy. He’s unpretentious, exuberant, and funny.

- Most Likely To Make You Wince: Keith McNally, I Regret Almost Everything – Frank, well-written, painful and witty by turns. An inside scoop on the restaurant business.

- Most Likely To Make You Drop Everything and Move to Southern France: Peter Mayle, A Year in Provence, Twenty-Five Years in Provence, Toujours Provence [Ed. – Blasts from the 90s past!]

Best non-foodie memoir:

- Amy Liptrot, The Outrun – The narrator leaves her dissipated twenties in London and returns to Orkney, in far northern Scotland, to find her footing. Interesting setting, well written.

Best novels:

- Kiran Desai, The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny – For many years Desai’s previous book, The Inheritance of Loss (2006), has been my favorite novel; I’ve waited with much anticipation to see what she would do next. The wait was not short. But Loneliness, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, is so worth every bit of time Desai took to conceive and compose it. It’s a big, complicated book about art and identity and love and family and borders. Along with the big themes, she remains fantastic at rendering small moments: passing observations and exchanges so apt and droll you want to keep them at your fingertips.

In fact, this book has many of the same qualities that shone in Inheritance: sly humor, exasperating minor characters who unexpectedly endear themselves to you, and tensions between isolation and community, truth and cant, haves and have-nots. But over two decades those polarities have become more extreme and their effects more pernicious. Desai’s sensibility has grown more weary and embittered (hasn’t everyone’s?) [Ed. – yes], and to encompass all it sets out to, this new novel is necessarily larger, messier, more brooding and less ebullient.

- Kevin Barry, The Heart in Winter – Irish love story meets American Western. [Ed. – Good description, good book.]

- Niall Williams, This Is Happiness and The Time of the Child – Wonderful reads, with an Irish lilt to the prose that only deepens enjoyment. These are connected and I recommend starting with This Is Happiness.

- Megha Majumdar, A Guardian and a Thief – A nail-biter set in the all-too-believable near future; the writing is strong and fresh. For instance: I happen to be aware that there are lots of saccharine quotations out there about hope (even by Dickinson!—“‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers…”—ugh). [Ed. – Surprising fighting words!] Majumdar’s take on hope is gloriously unsweet:

Hope for the future was no shy bloom but a blood-maddened creature, fanged and toothed, with its own knowledge of history’s hostilities and the cages of the present. Hope wasn’t soft or tender. It was mean. It snarled. It fought. It deceived. On this day, hope lived in the delivery of gold to a man who might be a scammer, and, perhaps, hope lived also in opening the doors to a thief.

Another great line:

He [the interloper] smelled of the soap Dadu [the protagonist’s father] had used, palming old sliver to new bar, decade after decade.

“Palming old sliver to new bar, decade after decade”—I know Dadu from that line, as well as if I smelled his soap scent. [Ed. – Indeed! And “palming,” which I only usually hear in reference to cards, makes it sound like he’s doing something a bit disreputable.]

Runners-up: Another near-sweep for the Irish!

John Boyne, Mutiny: A Novel of the Bounty [Ed. – Allowing this only because it’s you, Hope. We don’t like the Striped PJ man around here.]

Cólm Toibín, Nora Webster

Mary Costello, Academy Street

Weike Wang, Rental House

Most Unusual Best Novels:

- Isabel Cañas, Vampires of El Norte – I thought I didn’t like vampire novels. Yawn. But this novel serves them up veiled in themes of colonialism and environmental exploitation, while also working well as a love story and as plain old horror. [Ed. – Horror one of the most vital genres right now!]

- Samantha Harvey, Orbital – Great premise for a novel, and so many stunning descriptions—but too many plotlines are left flying at the end.

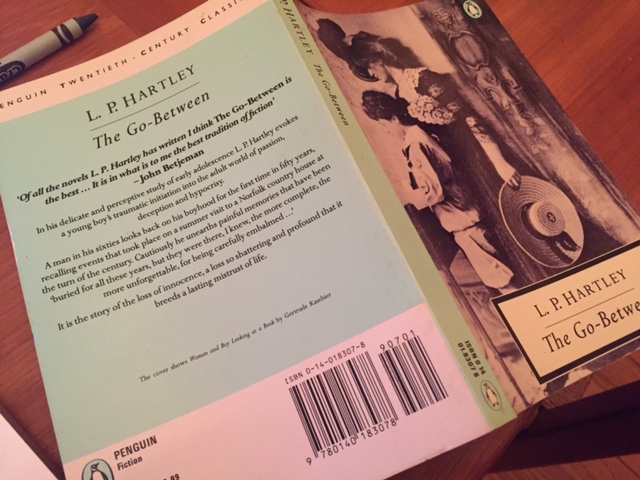

Best Classic That Stands Up to Time:

Willa Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop – Bestowing superlatives in literature is kind of silly, ever more so as time goes by. Still, if I were forced to name the Greatest American Novelist, I would say Willa Cather. In this novel Father Jean Latour, a French-born priest, gets appointed to serve a vast area of New Mexico just after its annexation. His life in Santa Fe provides the central narrative, and on this armature Cather strings a number of side stories that she took in during her long visits to the area—some harrowing, some strange, stories of depravity or folly or pity, but all told with her characteristic quietness and exactitude. A lesser writer might have expanded one or two of these to fashion a more conventional main plot, say the story of the lost El Greco, or Father Latour’s lifelong dream of building the Santa Fe Cathedral. But Cather avoids imposing such a goal-driven form. The more organic structure that she chooses instead keeps our attention on the place and its inhabitants, emerging gradually into solidity. [Ed. – Such an enticing description!]

One of the book’s brilliant strokes is its prelude on a terrace in Rome, where over dinner three Cardinals and a Bishop are hashing out the jurisdiction of these territories so remote they might as well be on another planet. After this the novel returns to Europe only in brief flashes. Yet these bits of Old World context, in a novel about the relentless development of the American West, are somehow key to its power.

Series That Never Disappoint:

Robert Galbraith,* Cormoran Strike series | new in 2025: The Hallmarked Man

Michael Connelly, Harry Bosch and Renée Ballard series | new series in 2025 set on Catalina Island: Nightshade

These series are my jam: character-driven investigator mysteries possessed of zest and depth. Authentic settings, dialogue that people would actually say, multiple unfolding plots.

*Yes, Galbraith is aka J. K. Rowling, and yes, she is toxic on the subject of trans rights. I’m shocked by how a writer with her insight and empathy into human character can be so hateful toward an entire subjugated group of people… yet I continue to love her books. Read Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer if you judge me for this or if you too struggle with this conundrum. [Ed. – I don’t judge you, but I had to give up these books, which I very much enjoyed because she really seems a terrible person, and TERFs suck. I would like to read the Dederer, though.]

Best Potato Chip Fiction:

This is my husband’s term for books that may not be the highest order of literature, but they’re well done and so satisfying to read that you just keep ingesting them like potato chips that you can’t stop eating.

Lian Dolan, Abigail and Alexa Save the Wedding – I’ve gone on to read a few more of Dolan’s books, but this one is my favorite, with little gems of observation such as:

Alexa was one of those women who had aged in place, meaning that Abigail could still see the eighties undergrad and the focused career gal and the bold single mom in her sixty-something face. Some people disappeared into their later years’ appearance, no trace of their young days left, thanks to injectables and surgery. But not Alexa. She was all she had been.

Lisa Jewell, The Night She Disappeared, Don’t Let Him In, etc. [Ed. – I have been eyeing these…]

Best Nonfiction:

Lynne Olson, Madame Fourcade’s Secret War: The Daring Young Woman Who Led France’s Largest Spy Network Against Hitler

Elizabeth Letts, The Ride of Her Life: The True Story of a Woman, Her Horse, and Their Last-Chance Journey Across America

Liza Mundy, The Sisterhood: The Secret History of Women at the CIA

Jordan LaHaye Fontenot, Home of the Happy: Murder on a Cajun Prairie

Most Depressing Nonfiction:

Kirk Johnson, The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century – Just typing the title, I get depressed all over again. [Ed. – Well, you made me look this up and now I’m intrigued. We really need a moratorium on these nonfiction book subtitles, though.]

Nonfiction Most Guaranteed to Make You Grip the Arms of Your Chair and Be Relieved They’re Not the Gunwales of a Boat:

Hampton Sides, The Wide Wide Sea: Imperial Ambition, First Contact and the Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook

Children’s Notables:

For a middle-grade novel I’m writing, I’ve been reading some classics of that genre. Here are three that I read or reread last year that wowed me.

William Pène duBois, The Twenty-one Balloons – I loved this inventive book as a kid, and turns out I still do.

Marguerite de Angeli, The Door in the Wall – How did I miss this one during my middle-grade years? Maybe I thought I didn’t like medieval settings: they’re so often gussied up with stale trappings of fantasy. But here the world-building feels solid and genuine. Good read.

Ann Petry, Harriet Tubman: Conductor on the Underground Railroad – Before reading this I knew only the broad outlines of Tubman’s life, and the fuller story blew me away. It’s billed as a young adult book, but nothing about it felt juvenile. Highly recommend. [Ed. – Fascinating! I did not know Petry wrote for children, too. I will pick this up.]

Thanks for reading; I welcome your comments on any of the above! And thank you, Dorian, for keeping this wonderful blog and for giving me a turn in your bully pulpit. [Ed. – Ha, nowhere near influential enough for that! Thanks for this piece, Hope!]