Friends, I am here to apologize to Matt Keeley, who wrote this great piece for me many months ago and has waited patiently (or maybe fumed silently) for me to publish it. I have no good excuse: I got busy and forgot. Terrible. Anyway, this really is a case of better late than never.

Matt is a freelance writer living in Boston.

Being a reader and working with books can, oddly enough, feel like mutually exclusive propositions. I spent most of 2024 underemployed, but what work I had before starting a new full-time job in October was mainly book-related. I copyedited and wrote pitches for a Dutch literary agency; I did brief manuscript reports for a literary scouting firm; I did occasional reviews for Reactor, The Washington Post, and The Boston Globe. I spent so much time on “professional” reading, including dozens of titles that I would normally have no interest in, that my personal reading suffered.

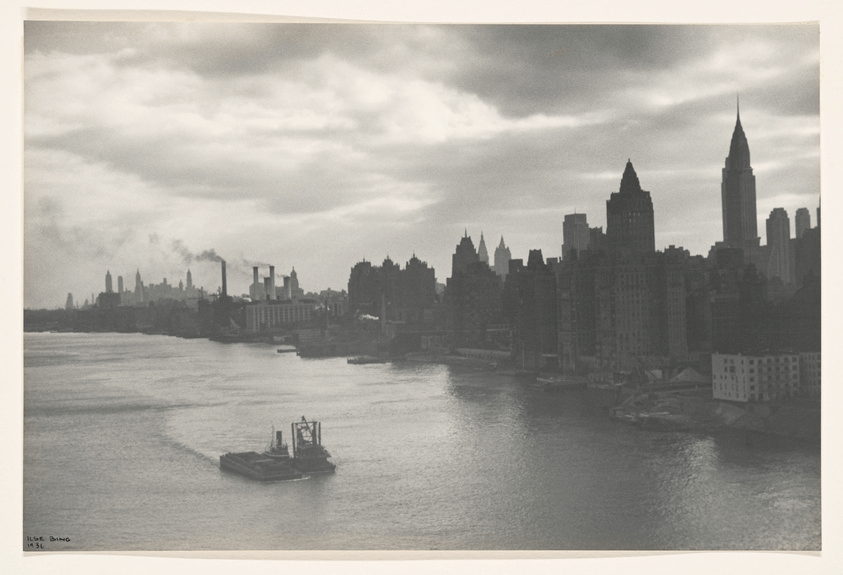

E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime was not the book I expected it to be: one somehow doesn’t expect a book this strange to sell a million copies, end up on movie screens, and inspire a Broadway musical. This is an almost essayistic historical novel, with an intrusive and opinionated narrator, major characters who go titled (Father, Mother, Younger Brother) but unnamed, and plot lines that don’t tangle so much as split. Henry Ford and JP Morgan discuss reincarnation in front a stolen Egyptian mummy; Emma Goldman befriends a notorious “kept woman;” in the epilogue, we learn that one character gets killed in the Mexican Civil War, that another sinks with the Lusitania, and that a third creates the Little Rascals franchise. It’s a deeply weird book. [Ed. – Colour me intrigued…]

The movie, incidentally, is quite good, with James Cagney’s final performance, an uncredited appearance by a young Samuel L. Jackson, and Norman Mailer as an ill-fated libidinous architect. I wonder how many New York literati of the 1980s especially enjoyed watching his death scene? [Ed. – Probably still satisfying today.]

Ruth Scurr’s John Aubrey: My Own Life is an unusual biography that repurposes the words of the great antiquarian and his contemporaries to create a sort of hypothetical autobiography. There’s much that remains unknown about Aubrey’s life, and Scurr would rather leave open a gap than speculate. That means, for example, that we get more about the stones of Avebury than we do about Aubrey’s romantic life, more tossed-off preference than deeply felt emotion. This is an eccentric book about an eccentric man; most readers won’t much like it, but a few, like me, will love it. [Ed. – In the immortal slogan of Halifax’s Alexander Keith’s brewery: “Those who like it, like it a lot.”]

Gone: The Last Days of The New Yorker is Renata Adler’s score-settling memoir about the departure of William Shawn, the arrival of Robert Gottlieb, and the eventual appearance of Tina Brown. At one point, Adler compares Adam Gopnik to Anthony Powell’s Widmerpool. If you recognize the names in the last few sentences, you’ll likely enjoy this book, even if you don’t entirely trust it. Otherwise, you’d best avoid.

Rejection by Tony Tulathimutte is the dirtiest book I’ve read in ages. [Ed. — !] It seemed to come out of nowhere: I’d never heard of book or author until an editor asked me to review it. I invoked Philip Roth in my review, and I stand by that comparison:

Its heights, or depths, of exuberant filth reminded me of Philip Roth in Portnoy’s Complaint or Sabbath’s Theater. Like Roth, Tulathimutte knows desire can be as ludicrous as it is urgent; like Roth, he likes a good dirty joke.

Other highlights of 2024’s reading include:

- Peter Straub’s Koko, a serial killer story with fine writing, memorable characters, and all too much exoticizing of the mysterious Orient [Ed. – It’s so mysterious tho]

- Six of Georges Simenon’s Maigret novels — I really need to get back to the romans durs soon, but there’s something comforting about Maigret even when the plots are, in fact, quite harrowing

- Amit Chaudhuri’s A Strange and Sublime Address, his first novel, as elegantly written and absorbingly plotless as later books like Friend of My Youth and Sojourn [Ed. – Read this last year as well: good stuff]

- Paolo Bacigalupi’s Navola, the sequel to which cannot come soon enough. (Dorian — There’s a strong Guy Gavriel Kay influence here. I think you’d like) [Ed. – I appreciated this tip enough to check it out of the library—it indeed looks quite my thing—but not, apparently, enough to read it yet…]

- M.T. Anderson’s Nicked, a fantastical medieval heist novel and queer romance [Ed. – Octavian Nothing was fantastic.]

- Adam Roberts’s Lake of Darkness, a science fiction novel about Satan, post-scarcity, and what happens when you let AI do all your thinking

- Howard Norman’s My Darling Detective, a thoroughly charming tale hampered only by the author’s difficulties with continuity and his editor’s failing to notice the innumerable discrepancies and inconsistencies. Read for the vibes, not the details. [Ed. – Yikes!]

Two that got away

One sad effect of all my book work was that I struggled to finish long and complicated books. I got maybe eighty pages into Oakley Hall’s classic Western Warlock before I gave up. The prose so fine, the type so small, the pages so numerous: I enjoyed and admired the book, but it took two weeks to traverse less than a hundred pages. [Ed. – Ha! Nicely put! It’s not easy, that one. Took me a while to fall under its spell.] I felt myself losing the thread, and put the book back on the shelf for a less fraught day.

Something similar happened with Iris Murdoch’s The Black Prince, which I’ve had on my shelves since 2007. In a burst of optimism, I’d bought three Murdoch paperbacks when I was a college student studying abroad in Dublin. I quickly read A Severed Head and hated it, and so The Sea, the Sea and The Black Prince sat unread for more than a decade. I knew, however, the problem was more with Matt than with Murdoch, so every year I vainly promised myself I’d give Murdoch another shot. When I finally took the plunge last June, I was thrilled to find that The Black Prince was smart, funny, and satirical, bursting with memorable images and sparkling with ideas. Except, once again, I found myself losing the thread and regretfully set the book aside.

I ended up reading The Bell, another Murdoch, in January of 2025. Perhaps I’ll get through The Black Prince later this year? [Ed. – Because it took me so damn long to get this up, maybe he has!]

Last year’s books, this year

Finally, there are a few 2024 books that I bought and fully intended to read, but haven’t quite gotten around to. First is Percival Everett’s James, a novel which sold a million copies and made nearly as many end-of-year lists. I’ve enjoyed Everett’s past novels and I’m sure I’ll tear through this one when I get around to it. Incidentally: I wonder when Everett’s next book will be? He usually seems to write about a book a year; I wonder if they’re holding off publication until James sales begin to taper off?

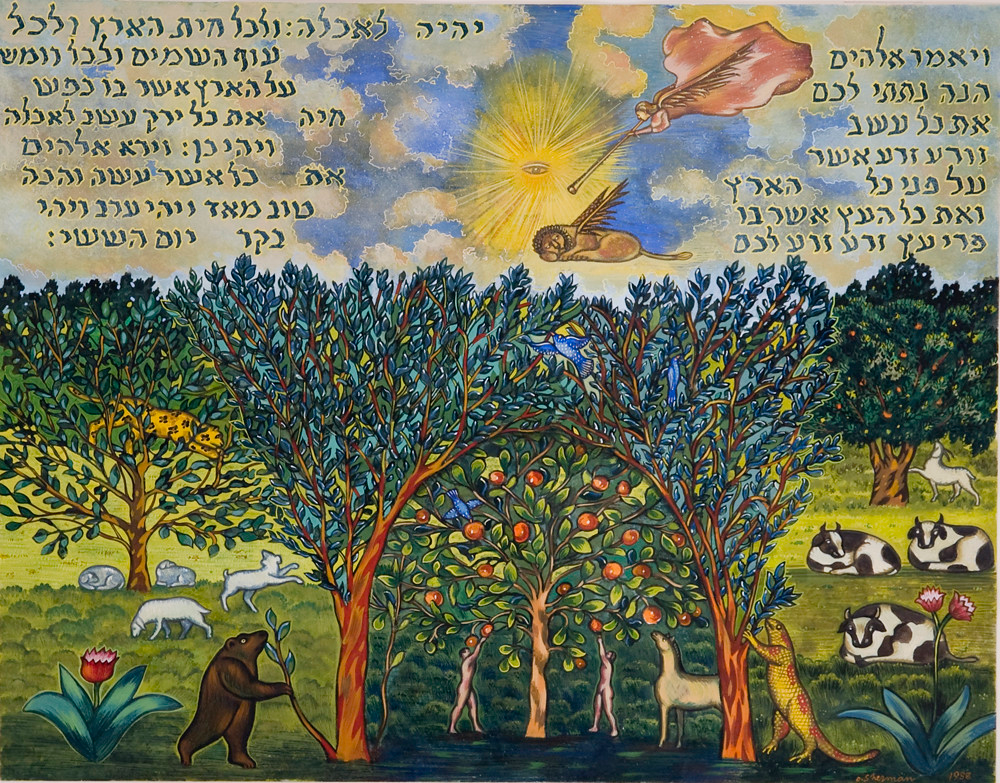

Next is Cahokia Jazz by Francis Spufford. I pitched it for review, but the pitch was declined. [Ed. – Boo!] I’m reading it now and am impressed: It’s simultaneously a murder mystery, a literary novel, and an alternate history. Spufford dedicates the book to “Prof. Kroeber’s daughter;” I wonder if Prof. Kroeber makes an appearance in the book. The period is right, Kroeber was an anthropologist interested in Native Americans, and there are lots of Native American characters in the book. [Ed. – SO good!]

Last is Ed Park’s Same Bed Different Dreams, which looks to be a polyphonic metafictional conspiratorial genre bender. I’ll probably turn to this once I finish Cahokia Jazz. [Ed. – Also good, with plenty of hockey. Thanks, Matt! Sorry again for dropping the ball!]