Labour Day made for a short week. Wednesday saw us conclude the first unit of the course on narrative event with Vladimir Nabokov’s wonderful, too-little known story “The Fight” (1925). Today saw us begin a unit on character with the first of several stories we’ll be reading by Bernard Malamud, the enigmatic “The Mourners.”

Once again I’ve assigned Malamud’s third book, The Magic Barrel (1958), one of the few story collections ever to win the National Book Award. We’ll be returning to it regularly this semester. I love this collection and I was really pleased last time I taught the course that students liked it a lot too. I really wasn’t sure that would be the case. They’re very Jewish, these stories, and my students are not. That last group was much more Humanities oriented than this one seems to be, but at least reading a single author in some depth will help them as they prepare for the final essay, in which they’ll examine the formal and thematic preoccupations of an author as they are manifested in four or five stories from at least two collections.

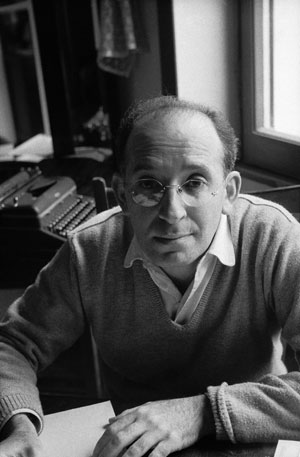

I spent some time at the beginning of class telling the students a little about Malamud. Normally I don’t do this, we just don’t have time, but it seemed worth doing today. The result, however, was that, after describing Malamud’s childhood in Brooklyn with parents who had escaped Tsarist Russia—real Fiddler on the Roof stuff, I said, and was shocked by the sea of blank faces: only two students had ever seen it—a childhood that was poor, the parents working long hours at a small grocery of the sort that appears so often in Malamud’s fiction, and difficult, the mother institutionalized after a failed suicide attempt (she was found by Malamud himself) and a brother similarly plagued by schizophrenia, a childhood that Malamud escaped by becoming a teacher, an occupation he continued through his marriage to a Catholic (bitterly contested by both families), a stint at a land-grant university in Oregon, and a fellowship year in Rome before landing a permanent gig teaching college writing at Bennington College in Vermont, where he painstakingly worked on his highly polished sentences, a determined, almost monastic life made famous in Philip Roth’s lightly fictionalized, and overtly hostile representation of Malamud in The Ghost Writer (1979)—after saying all this we only had about 40 minutes left to discuss the story.

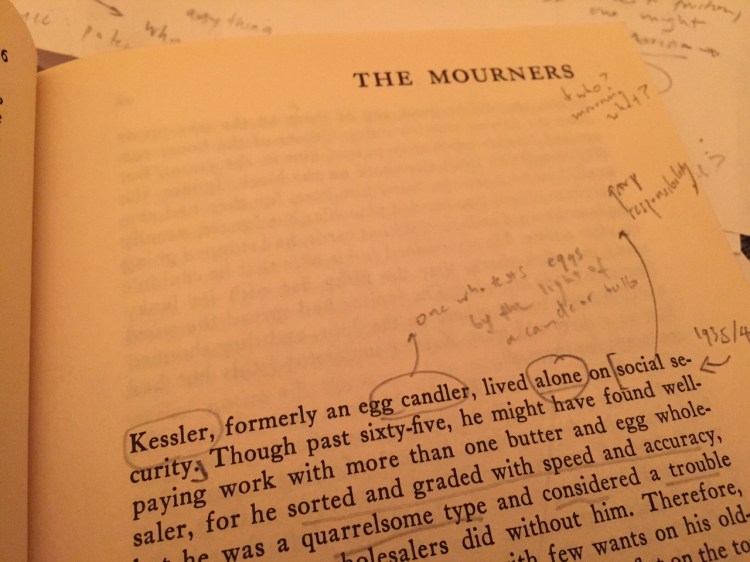

Moreover, we spent so long analyzing the first sentence—“Kessler, formerly an egg candler, lived alone on social security”—that we didn’t have time to say everything I wanted to about the story. But I thought it worth lingering on that sentence for two reasons: one, I always love beginnings, and two, I think this one is quintessential Malamud. His economy is evident, as is his lack of patience with extended exposition. We considered two things in this sentence that are present at the beginning of almost all his stories: the use of last names, and the reference to occupations.

I was relieved that most students had found out what an egg candler does. (I hate it when students don’t look up words.) When I asked them what images came up in their google searches, they described various machines, devices, or contraptions that involved a light source. Not, I observed, any pictures of guys looking at eggs. This led them to conclude that egg candling must not be done by people any more. Which might mean what? Maybe that it’s boring, repetitive, the kind of thing people don’t do as well as machines. Kessler, on that reading, would be a superfluous man. That proves to be true, in a way, yet we also learn, in the next sentences of the story, that Kessler had been fired by “more than one egg and butter wholesaler” not because he was a bad worker—“he sorted and graded with speed and accuracy”—but because he was “a quarrelsome type and considered a trouble maker.” There are plenty of quarrels in the story (one reason I wanted to pair it with the Nabokov), but Malamud’s phrasing leaves open the possibility that he might not really be a troublemaker, he might just be mistaken for one, and thus perhaps not a bad guy, or as bad a guy as he seems.

At any rate, we learn here in passing something important: that the job of egg candler, which might seem dull and repetitive, actually requires discernment, even finesse (all that sorting and grading). Those qualities are important to keep in mind, since they might make us feel more kindly towards Kessler later on. For our opinion of Kessler quickly takes a nose dive, since we learn that thirty years ago he suddenly abandoned his wife and children, merely because he is “unable to stand” them—they had been, the story chillingly tells us, “always in his way.”

The distance we soon feel towards Kessler is intimated already in the use of last name, which students pointed out removed the characters from us—and from each other. Through my prompting, they noted that this story—set almost entirely in a single tenement building in which people live on top of each other—is filled with characters who hardly know each other, and don’t seem to like each other much when they do.

Kessler gets into a fight with the janitor in his building; the janitor tells the landlord, one Gruber, a big sweaty man with high blood pressure caused from his desire to wring as much money out of his run-down building as possible. Gruber gives Kessler notice, but Kessler won’t leave. Gruber has Kessler evicted, but Kessler sits in the snow on the sidewalk until his neighbours take pity and file the lock off the door and carry him back upstairs. Kessler asks Gruber plaintively, “‘What did I do, tell me? Who hurts a man without a reason? Are you a Hitler or a Jew?’” As he does, he is all the time hitting his chest with his fist, an allusion to the prayers of atonement Jews offer on Yom Kippur, the striking of the chest with the fist metaphorically suggesting how much we must take the task to heart.

The next day—after the landlord spends a restless night worrying over how to get Kessler to leave, just one of several references in the story to Melville’s marvelous “Bartleby, the Scrivener” (1853)—Gruber ascends the stairs of the building only to find Kessler still in the apartment. Now Gruber sees Kessler as a mourner, and indeed we learn that Kessler is thinking about what he has apparently been thinking about ever since being evicted to the sidewalk, namely, his having abandoned his family.

At the end of the story, Gruber, who has a sudden vision of falling down the stairs that are referenced so often, becomes convinced that Kessler is mourning him. The final paragraph reads:

At last he could stand it no longer. With a cry of shame he tore the sheet off Kessler’s bed, and wrapping it around his bulk, sank heavily to the floor and became a mourner.

What exactly the two are mourning, and why they mourn rather than, say, repent, is just one, though perhaps the most important, of the story’s many enigmas.

As a way to solve those mysteries, I asked the students to free write for a couple of minutes in answer to the question: “Who does the story ask us to sympathize with?” (I later introduced the term “identification”—a fancy way of describing our tendency to model ourselves on others, which involves looking for others that we want to be like.) I thought this was a good question to ask of “The Mourners” because it has no obvious answer. I’ve often found that asking students to write for a bit half way through class leads to good results: sharper thinking, more nuanced answers. That was true this time, too, as became evident when I asked a few of them to read their responses. Most answered Kessler, one Gruber. No one, I noticed, but only to myself, there just wasn’t time, though I see now it would have been helpful to bring it up, said the old Italian woman, Kessler’s neighbour, who shrieks and shrieks when she sees Kessler on the street without pause until her grown sons carry him back up to the room. I don’t understand this moment, really, but it’s one of the only times when someone in this story cares for somebody else.

Perhaps the old woman sees her own fate in Kessler’s. After all—and I regret that I didn’t say this in class—the other piece of information in the story’s opening sentence is that Kessler lives on social security, an unremarkable fact to readers today, especially eighteen-year-olds, but more remarkable given the time of the story’s writing and its setting, which is never directly named but seems to be a few years earlier. But social security only dates to 1935, and it wasn’t offered as a regular monthly sum until 1940. This historical fact connects to the story’s interest in what it means to care—or not to care—for others. One way to understand social security is as an affirmation that we will all care for each other, even those we don’t know (by “all” I mean Americans: proving one’s bona fides as an American is an abiding concern in these stories, filled as they are with Jewish immigrants). It’s a way of generalizing responsibility. I don’t think the story disputes that social security is good, even very good, but I think it might be suggesting it’s not enough. Maybe the idea is that each of us must take responsibility for our friends, loved ones, and neighbours. Perhaps this failure is what is mourned. For the accusation Kessler levels at Gruber—“Who hurts a man without a reason?”—could be asked of Kessler himself. After all, that’s what he did to his family.

Things got rushed at the end of class, just as they are here. We didn’t have time to really grapple with these ideas of responsibility. The period didn’t feel wasted, but it didn’t feel as satisfying as I’d have liked. “The Mourners” is remarkable, though, and I urge you to read it, especially now, on the eve of the Jewish High Holidays.

I haven’t time or energy to say much about “The Fight,” the other story we read this week. It too is wonderful. Nabokov’s stories are underrated, especially the ones from his time in exile in Berlin in the 1920s. “The Fight” has an odd structure. It begins with a lengthy description on the part of the first person narrator—an émigré in Berlin, presumably someone like Nabokov himself—of the excursions he regularly makes to a lake on the outskirts of Berlin, perhaps some place like the Wannsee, which would later take on such a sinister associations because of the decision taken at a villa there in 1942 by top Nazis to exterminate European Jewry. At the period of Nabokov’s story, though, the lake is merely a place to swim and sun. The narrator regularly sees an older man there, a man with whom he can only haltingly converse, but who seems genial and pleasantly anarchic. For example, he warns other bathers of the arrival of the hated dogcatcher with a piercing whistle and a glint in his eye.

Only later does the narrator discover more about the man, when he happens to enter a bar in an unfamiliar part of the city that turns out to be owned by him. The narrator begins to drop in regularly, watching the goings on of the regulars, especially the love affair between the daughter of the man—his name, we learn only relatively late in the story, is Krause—and a young electrician. The last part of the story tells what happens one day when the weather is sultry and a storm just about to break. The electrician stops by the bar, pours himself a drink, and makes himself on his way. Krause demands that he pay; the man refuses, saying that, after all, here he is at home. Matters escalate rapidly and in a matter of a sentence or two the men are fighting with bare fists on the street, to the glee of a crowd that has gathered seemingly from nowhere. Krause knocks the electrician out. The narrator vainly, rather heartlessly, attempts to comfort the girl with a kiss. And that’s it. The story’s over.

For me, “The Fight” is a parody of the chart known to every high school student, the one that details initial exposition followed by gradually rising action that leads to a climax and then comes down to a resolution. Instead of those hoary conventions, this story asks instead: In what way does a climactic action need to be prepared for? What happens if that action isn’t resolved?

Wednesday was the first rainy day of the semester, and I knew the students would be listless. So I divided the students into groups and gave each a question I’d prepared beforehand. In lieu of any interpretation of the story—read it, it’s about five pages, and fabulously Nabokovian with its disturbing first-person narrator, you won’t be disappointed—I’ll simply list them here. I’ll take your answers in the comments below.

- Why is this story called “The Fight”? After all, the fight doesn’t take up much of its length. What is the fight like? What does it lead to? What is the story telling us about it?

- We could divide the story into three parts: pp 141-3//143-4//144-6. What do the parts have to do with each other? Why all that stuff about swimming at the beginning?

- What is the narrator like? What do we learn about him, even if indirectly?

- What does the story tell us about bodies?

- How does the anecdote about the dogcatcher function? What’s it doing here?

- How does the final paragraph affect our understanding of the story?

Another short week next week, what with Rosh Hashanah. And the demands of the semester are really tightening. But I’ll do my best to report back here again when we turn our attention to two much more recent stories.