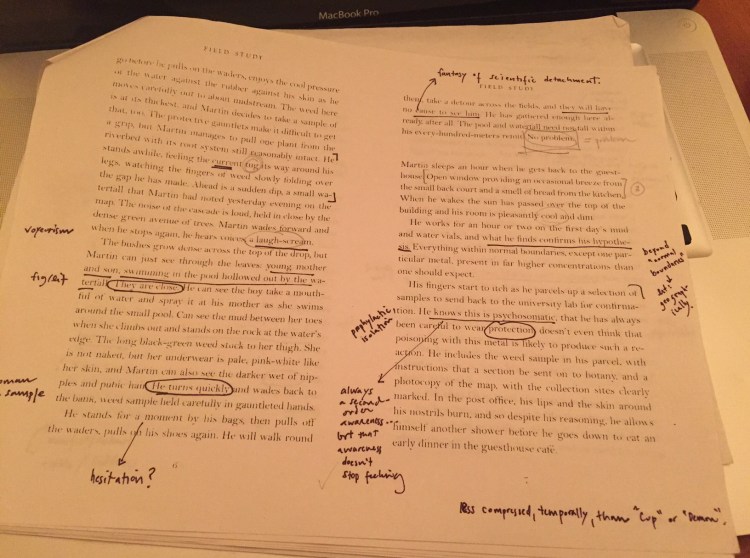

As I mentioned last time, after discussing Lawrence we launched into three days of writing workshops, in advance of the first paper, due yesterday. Of course this isn’t the first writing they’ve done: they’ve each turned in two (of four) two-page reading responses.

I use these writing workshops to force students to start writing earlier—and to recognize that writing means rewriting. Most Hendrix students did very well in high school, often with minimal effort. My students regularly admit—and this group is no different—that they typically wrote their high school papers the night before, and that worked out just fine for them. But it doesn’t work any more.

For this first paper, I’d given the students prompts to choose from. (The next one will be quite different.) Before the first workshop, I asked students to do two things. First, find five passages from the story they had chosen to write about that they thought they might use in the paper. Second, complete a timed writing exercise adapted from the writing guru Peter Elbow. The instructions were: write for fifteen minutes without stopping about whatever comes to mind about your topic. Then revise lightly for five minutes. Set the writing aside for a day. Read it over, open a new document, write again for fifteen minutes, and revise again for five.

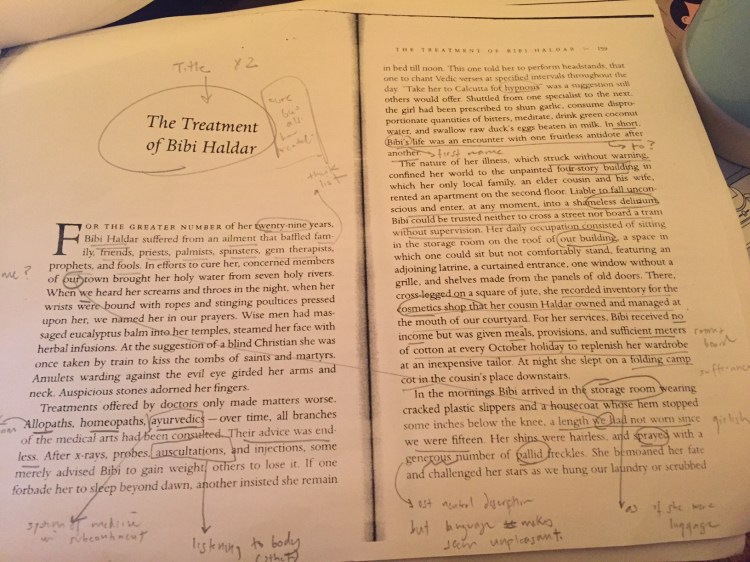

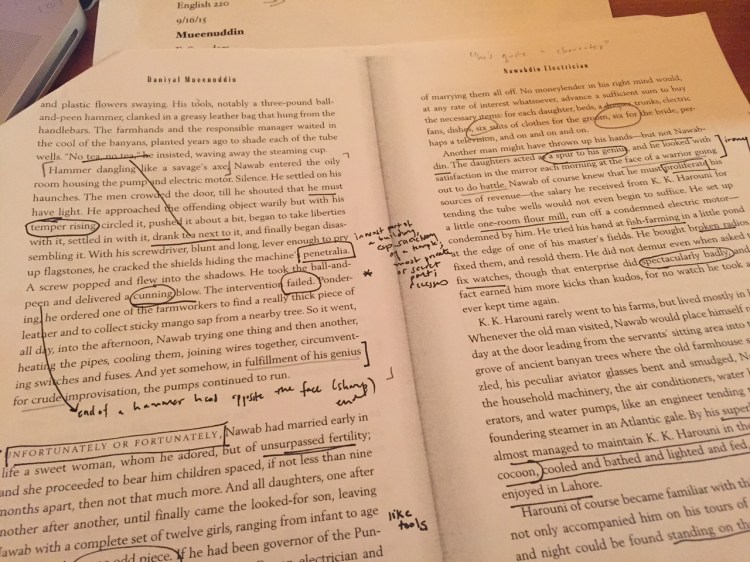

Students emailed me the second document by midnight the day before class, and brought their quotes to class. I organized the class into pairs (putting stronger and weaker students together where possible) and instructed students to arrange their partner’s passages in different combinations to suggest different interpretations. In addition they had to choose one passage to close read (to mark up with suggestions about how the way something is said affects what it says). Even though we do nothing but close read in our class discussions, students still struggle with this task. I sat in with a couple of groups who seemed to be finished far too quickly and worked through a passage with them.

In the last third of the class, I passed out one of the fifteen-minute writing paragraphs students had sent me, one that seemed representative of where most students were at in their writing process (having removed the author’s name, of course). What advice would they give the writer about how to proceed? My first question in such exercises is always the same: What is the best moment in this piece of writing? Where is the writing most alive, most compelling? Students are usually pretty good at pointing that out. They just need help knowing what to do with it once they’ve found it. I teach students how to extract the kernel of their writing—the key idea, invariably confused and under-developed at this point—and make it the basis for their draft.

A draft is what they needed for the next class, which wasn’t a class, but an individual meeting with me. (That took most of one day and part of the next.) Those meetings are quite draining for me—although at least I’ve managed to train myself to read the draft in the meeting itself: I used to do all that beforehand—but the results are worth it. At a certain point, students need individual attention to their writing, and they’re not good enough yet to peer review each others’ drafts usefully.

All of this took us through the end of last week. On Monday we met as a group to talk about citation and line editing. I addressed a few recurring mistakes and stylistic issues before passing out a sheet with sample sentences from the writing they’d already done that semester. I asked students to revise these sentences for clarity. Some of the sentences had grammatical mistakes, but that wasn’t the real problem with most of them. These students don’t struggle with mechanics; they struggle with having something to say. The sample sentences either (a) didn’t say much of anything at all, which became clear when we cut the redundancies and wordiness or (b) weren’t sure what they wanted to say. Most problems in writing, I explained, are problems in thinking.

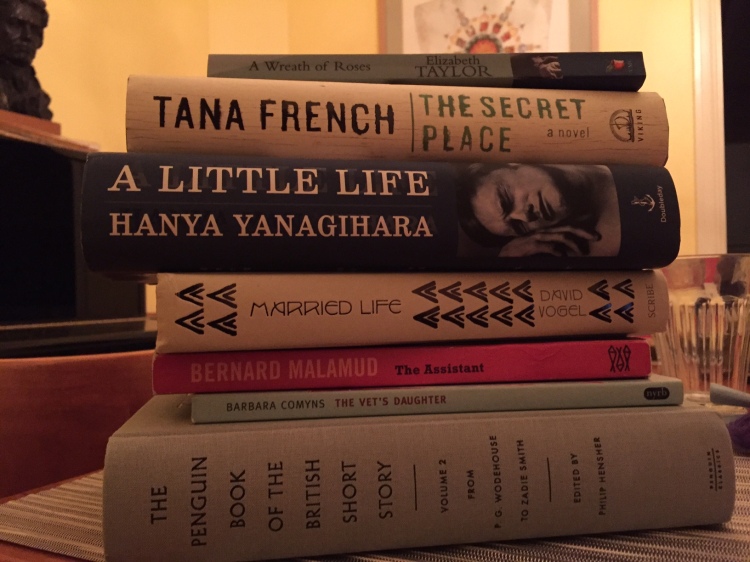

I’ll find out soon whether these workshops helped: I have the stack of papers in front of me. Even at first glance, though, they look better than the drafts. Undoubtedly many will still be mediocre. But I’ll be happy if none of them are terrible, and even happier if one or two of them are great.

Yesterday, then, was the first time in a while that we talked about a story. I knew the students wouldn’t be good for much: their papers were due that day, they had assignments or papers or exams in most of their other classes too, and it was the day before Fall Break. That’s why I had scheduled a very short story by Edith Pearlman called “Binocular Vision.”

For some reason every semester I usually assign one text I’ve never read before. Mostly this habit is self defeating, forcing me to scramble madly to get up to speed on something I know little or nothing about. But sometimes it’s helpful: when my knowledge isn’t that much greater than my students’ I tend to be a more accepting teacher, and there’s also the thrill of pulling off a pedagogical high wire act.

So it was for me with “Binocular Vision.” I’d read about Pearlman when she broke through into mainstream critical acceptance a few years ago (she’d published a few collections with small presses before that, but interestingly didn’t begin publishing until quite late in life—she’s born in 1936, and I think the first published stories are from the 1980s). Learning that she was Jewish only made me more interested. But I still hadn’t read anything by her.

When I made the course syllabus I was drawn to this story because it was the title story of the collection, because it was short (five pages), and because it was in first person (something I wanted to focus on, and that I would compare to the unusual second person address of an upcoming story by Jhumpa Lahiri). My hunch paid off. “Binocular Vision” is terrific, and a good story to teach on a difficult “last class before break” day.

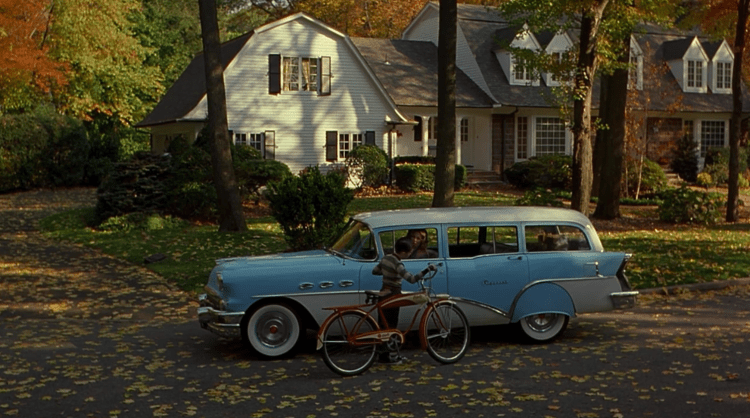

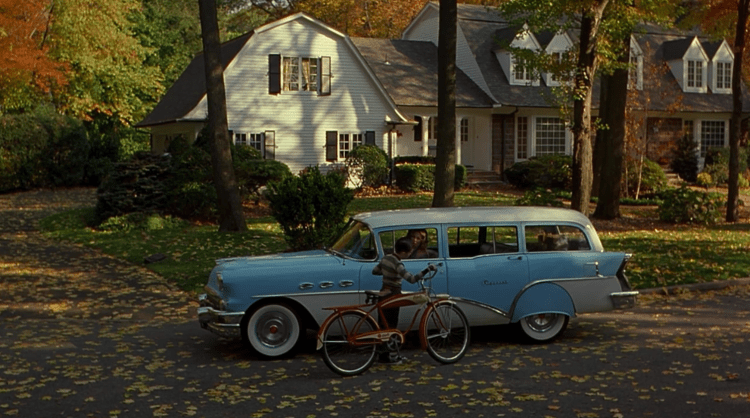

The story is told by an unnamed narrator, a ten-year-old child living with parents and sibling in Connecticut at an unspecified time that is probably the late 1950s, for we learn “There was no television, of course—only rich show-offs had televisions then.” In addition to giving us a clue about setting, that sentence also tells us that the time of the telling is later than the time of the events (“only rich show-offs had television then”). In a few weeks I’ll remind students of Pearlman’s use of a narrator who reflects on life, for this strategy will recur in our unit on the theme of childhood. For reasons that will become clear in a minute, Pearlman stays quite close to her narrator’s child perspective, seldom pointing out the disparity between then and now.

The story takes place in December over the school holidays. The narrator’s father, an ophthalmologist, has been given a pair of binoculars as a fortieth birthday present but he never uses them. One day the narrator idly takes them up and begins spying on the Simons, the neighbours in the apartment next door. Mrs. Simon is at home all day without much to do beyond tidying, running errands, and cooking supper. (“Serious cleaning was done once a week by a regal mulatto woman.”) The narrator sometimes runs across Mrs. Simon in the neighbourhood and shyly whispers a greeting but the elderly woman never replies. The most exciting part of Mrs. Simon’s day, and, before long, the narrator’s, is Mr. Simon’s return home from unspecified work. The narrator can’t see their greeting; the door is blocked from view. But after dinner, the child watches as Mr. Simon reads the newspaper with great deliberation and Mrs. Simon knits and talks and laughs without pause.

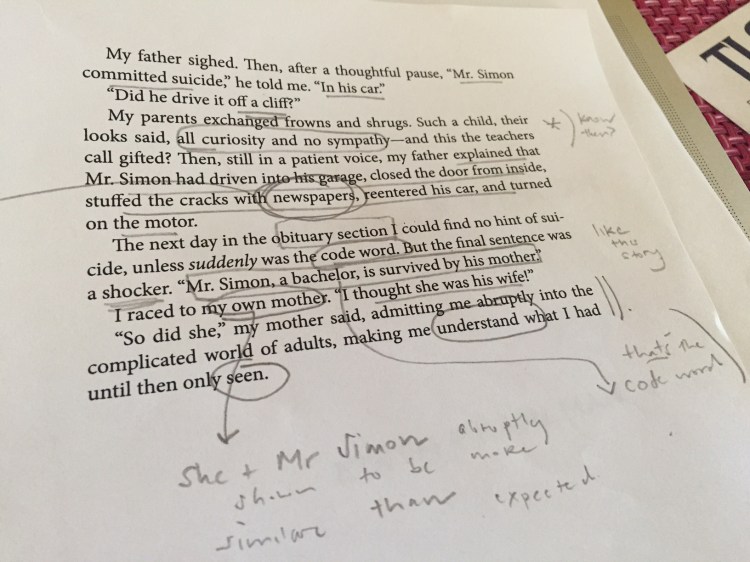

School starts again. The narrator has less time to watch the Simons, even starts to lose interest a little. But it comes as a shock when two policemen knock at the door one February morning to ask that the doctor accompany them next door. When he returns he explains to his wife and children that Mr. Simon has committed suicide in his car. Here’s the end of the story:

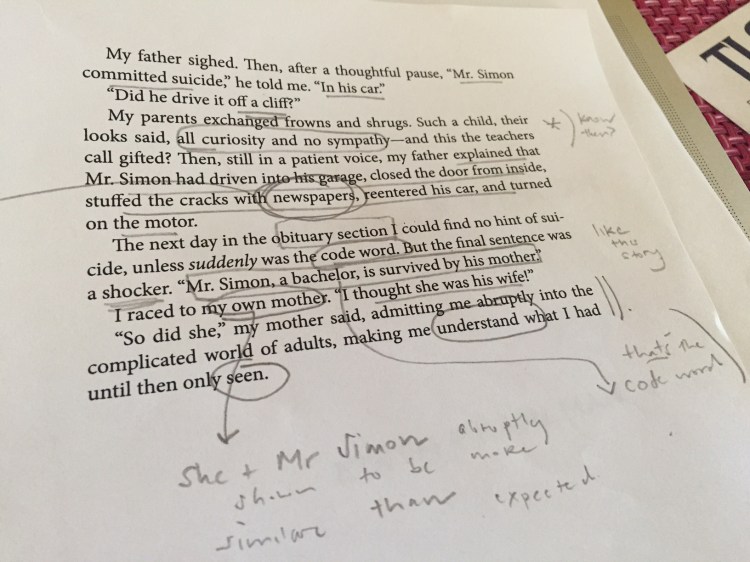

“Did he drive it off a cliff?”

My parents exchanged frowns and shrugs. Such a child, their looks said, all curiosity and no sympathy—and this the teachers call gifted? Then, still in a patient voice, my father explained that Mr. Simon had driven into his garage, closed the door from inside, stuffed the cracks with newspapers, reentered his car, and turned on the motor.

The next day, in the obituary section, I could find no hint of suicide, unless suddenly was the code word. But the final sentence was a shocker. “Mr. Simon, a bachelor, is survived by his mother.”

I raced to my own mother. “I thought she was his wife!”

“So did she,” my mother said, admitting me abruptly into the complicated world of adults, making me understand what I had until then only seen.

I began class by making the students move to different seats (they always sit in exactly the same configuration). They couldn’t sit in the same place on the opposite side of the room, and they couldn’t sit next to someone they always sit next too. This went exactly as it always does: first it livened them up, but before long it quieted them down. I think it was worth doing because I’m hoping that what has happened in the past will happen again this time: some students will be bold enough to start sitting in different places, which means they are more comfortable in the room, which is good for group morale. We’ll see. Today I was able to add that the exercise was relevant to our impending discussion, since the story is about how we think differently about things depending on the position we see them from.

Once the students had shuffled, half-grumpily, half-excitedly, to new seats, I had them work with their new neighbours to find passages from the story that they understood differently now than they did when they first read them. There were plenty to choose from. One group pointed to the description of the Simons’ apartment. When the narrator sees “a double bed with an afghan at its foot, folded into a perfect right triangle” we assume the Simons sleep in it together—but that must not be the case, unless things are even stranger between mother and son than the story otherwise suggests.

Another group mentioned the narrator’s description of what happens when Mr. Simon comes home at night: “He’d pass a hand over his gray hair, raise the door of the garage, get back into the car, and drive it into the garage. He usually sat there for a while, giving me a chance to inspect his license plate.” (This scene brought back childhood memories of having to get out of the car, always, in my memory, in deepest winter, to open the garage door for my parents. I refrained from forcing this sepia-toned Canadiana on the class.) Once we know how Mr. Simon dies, his choosing to sit for a while in the car seems ominous.

That’s not the only ominous thing here. The narrator’s voyeurism gave the students pause. He’s just watching him doing nothing, one said, indignantly. Why do you say “he,” I asked? Is the narrator a boy or a girl? A boy, the class chorused, or, rather, mumbled. Why do you say that, I asked? Does the story ever tell us?

It’s because he’s staring at them all the time, one student said, a student whose work has improved recently and who I have great hopes for. Why, is staring something boys do? I asked. My little brother likes to do it… she said, before faltering amid general laughter. There’s a reason we say Peeping Tom, not Peeping Tina, said another student, valiantly keeping us on task. But we know she’s a girl, said a third student, the one who, I recently learned, had been planning to be an English major until he took a class he really disliked last year and who I am desperate to return to the fold. Aha! I said. How do you know? It says so, he answered, on the second last page.

We turned to the passage:

How I yearned to witness Mr. Simon’s return. Alas, it always took place in that inner hall. It must be like my father’s homecoming: the woman hurrying to the door; the man bringing in a gust of weather and excitement; the hug, affectionate and sometimes annoyingly long; and finally the separation, so that two little girls rushing downstairs could be caught in those overcoated arms.

I tried to keep the narrator’s gender a secret when I summarized the story, though my contorted phrasing probably gave it away. But the story seems to want to keep it a secret too. How strange, I observed to the class, that the narrator narrates this scene almost in third person. Only the possessive phrase “my father’s homecoming” tells us that this scene is reality rather than fantasy. (There is fantasy here: but it’s of something the narrator can’t see: Mr. Simon’s homecoming.) As a class, we didn’t decide why Pearlman makes this choice, although seeing how she plays with expectations in this story, I’m inclined to think she wants us to assume the narrator is a boy and then to have to reverse our expectation.

If I’m anything to go by, though, Pearlman might not succeed in this. I assumed the narrator was a boy, too, even after having read this passage. (I was taken in by its odd phrasing.) It wasn’t until I read an article that referenced the ten-year-old girl who narrates the story that I even imagined it could be otherwise. Perhaps I’d succumbed to sexism (assuming male as default gender). Or perhaps like my students I too unconsciously gender voyeurism male.

When I teach the story again next semester—and I will, it’s a keeper—I’ll try to make more sense of its reticence in this regard. What I concentrated on this time was the first part of the sentence describing the narrator’s father’s homecoming. “It must,” she says. Crucially, these words reveal the narrator’s assumption that other people’s lives must be like her own. If she thought about it for even a second, though, she’d know that couldn’t be right. After all, the Simons don’t have any children. They’re not even, she learns, the Simons.

I said before that the story doesn’t emphasize the difference between the time of the events and the time of the telling. I returned to this topic by turning us to the story’s final paragraphs. I’m not sure how to understand that description of the parents silently communing over their daughter’s head when she asks whether Mr. Simon drove his car off a cliff—“Such a child, their looks said, all curiosity and no sympathy—and this the teachers call gifted?” There is no indication here that the narrator is retrospectively making sense of that moment, bringing her adult experience to bear on a fleeting but meaningful moment. But how could the child get all that from a single look? She doesn’t seem preternaturally acute. The reference, however ironic, to her being gifted is the first we are invited to see her as particularly sensitive. I’m also interested in the ventriloquism of what the parents are imagined to have been thinking to each other—“and this the teachers call gifted?” The syntax and that idiomatic use of “this,” surely spoken with a rising emphasis and intonation, is the only place in the story that Jewishness makes itself felt. But I’m already worried the class is finding the class too Jewish, so I let these observations pass unspoken.

But the oddness of this moment—in which we can’t pin down whether the child or the adult narrator is speaking—might make more sense when we think about the story’s conclusion. I observed that in reading the obituary the child makes her own use of the newspaper, less devastatingly than Mr. Simon, perhaps, but no less dramatically. Suicide isn’t mentioned, unless through the code word “suddenly.” The reference to code reminds us that the child has been playing detective, and in this sense acts even more than any first person narrator would as a stand-in for readers. “But the final sentence was a shocker.” Pearlman’s joke is pretty neat: the same could be said for this story’s (almost) final sentence.

“‘Mr. Simon, a bachelor, is survived by his mother.’” There’s another code word in this sentence, I said to the class, maybe the real code word. What’s a bachelor? An unmarried man, someone was kind enough to answer. I briefly sketched the difference between denotation and connotation. What does “bachelor” connote, I asked, convinced it would be obvious where I was going. I can’t even remember now how they answered, but nothing they said was remotely in line with what I was thinking. What about the way people might have said, “He’s a bachelor, wink wink, nudge nudge”? Blank stares. Exasperated, I said, People used to use “bachelor” as code for gay. Haven’t you ever heard that? They hadn’t. I told them I considered that a great victory but the difference between their experience and my own suddenly seemed dispiritingly vast. It made me doubt my reading. But for me this story takes place in Todd Haynes territory, tragically closeted life in the 50s.

Unnerved by the failure of this last gambit, I attempted to forge ahead. Look what she says next: “I raced to my own mother.” Note how that phrasing, that use of “own,” suggests how abruptly she has been shown to be like Mr. Simon in ways neither she nor we could have anticipated just moments before. Indeed, the word “abruptly” appears in the story’s final sentence, naming a mode, a change, an experience the story performs as much as describes.

Why, I wanted to know, is the story called “Binocular Vision”? Silence, that eternal silence of this class! I tried a left-field approach. I asked, Is anyone taking anatomy? Alas, the answer was no. So I explained what I had just learned the night before: binocular vision results from eyes with overlapping fields of view, which allows for depth perception. Prey animals have eyes on the sides of their heads, which means they have a wide field of vision (almost 360 degrees) but little depth of vision (their eyes’ visual fields barely overlap). Predator animals have eyes in the front of their heads. Their visual field is narrower, but their depth perception is much better.

How can you use that information to make sense of the story? More silence. I waited. But time was running short and I was losing faith in myself. Is the question too obvious, is that why you don’t want to answer? Amazingly, a student said yes. I’ve been thinking about her reply ever since. Maybe my problem with this class is that whenever I’ve been asking what I think are real questions they’ve been hearing nothing but rhetorical ones. Since I pride myself on asking good questions, I was hurt. And I wasn’t so sure the question was that obvious. Quietly I said, Tell me anyway. The student obliged: She learns how to see with depth. She learns what’s really going on.

Yes, I said, that’s right. But that’s only half the story. The title has another meaning too. Binocular vision also means the vision you get through binoculars. In principle that means better vision—I referred to a passage early describing the girl’s difficulty in getting objects into focus—but it also means narrow vision, blinkered vision. The narrator sees only what she wants to see, doesn’t see what the story allows us to recognize, that she is confusing real lives, presumably rather desperate ones, for a show. She has no television, but she has the Simons. After all, she calls the evenings in the living room—the man with his newspaper, the woman with her knitting, his silence, her talk—her favorite scene. The narrator marvels at how unceasingly the woman can talk, the same woman who won’t even greet her when they pass on the street. “Talking. Laughing. Talking again.” How desperate, even hysterical those actions seem once we re-read them in light of the story’s final events.

But before we condemn the narrator too quickly, before we judge her for projecting her own experiences on to others, before we conclude that the difference between understanding and seeing offered in the story’s final sentence is the difference between adults and children, and that this child has seen everything but understood nothing—before doing so, I warned, let’s think about ourselves. Let’s remember our experience of reading the text. Let’s be mindful that we too made assumptions and saw only what we wanted to see.

We’re adults. Yet we read the story, we saw everything, and we didn’t understand a damn thing.

Class dismissed. Enjoy your break.