Today‘s reflection on a year in reading is by Yelena Furman, her first for the blog. Yelena (@YelenaFurman) lives in Los Angeles and teaches Russian literature at UCLA. She has published academic articles, book reviews in the Los Angeles Review of Books and The Baffler, and fiction in Narrative. She and Olga Zilberbourg (@bowlga) co-run Punctured Lines, a feminist blog on post-Soviet and diaspora literatures.

Look for more reflections from a wonderful assortment of readers every day this week and next. Remember, you can always add your thoughts to the mix. Just let me know, either in the comments or on Twitter (@ds228).

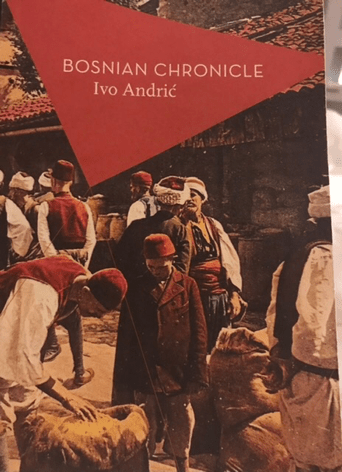

When Dorian asked me to compile my reading list for 2021, I was honored and it sounded like a lot of fun, but I did point out that everyone was going to make fun of me for how little I’d read in a year compared to how much other BookTwitter folks read in a month (including Dorian). [Ed. –Only a jerk would do this. There are jerks on Twitter, it is true. But they should at least know what they are.] I’ve always been a slow reader, and between technology, exhaustion, life in general, and now the pandemic, my concentration is shot. But as this post gives me a chance to promote works by contemporary Russian women writers that I taught this fall, the ridicule will be worth it. This list references a number of Twitter group reads in which I participated, and my sincere thanks go to their organizers, whom I hope I’ve credited correctly, and all the group members; your comments and camaraderie were wonderful parts of my reading year. Finally, there may be something I’ve left off or misremembered as having read last year, but what follows is as accurate a summary as my fried brain, and Goodreads evidence, suggest.

Marie Benedict, The Mystery of Mrs. Christie

A gift from my mom, who knows and shares my love of detective fiction and its foremost practitioner. No one would accuse it of being an intellectual work, but this fictional account of Agatha Christie’s real-life temporary disappearance was a page-turner and good escapist fun, and who couldn’t use that in an endless pandemic. [Ed. – Amen.]

Vladimir Nabokov, Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle

On the opposite end, this one’s beyond intellectual. I could never include Ada in my Nabokov course, not because of its theme of brother-sister incest but rather because its length and complexity make it impossible to fit into an already reading-intensive syllabus. For those not dealing with syllabi restrictions, this homage to eternal love and of course literature will give your brain a definite workout (this work’s meant to be reread) and is gorgeously written and often humorous to boot. I can’t say I love it, but as always with Nabokov’s English-language novels, I am in absolute awe of his dexterity as a writer for whom English wasn’t a native tongue.

Narine Abgaryan, S neba upali tri iabloka (Three Apples Fell from the Sky, trans. Lisa Hayden)

I read this novel as part of a Twitter group read, which was, like so many others, organized by the queen of collective Twitter readings, @ReemK10. [Ed. – All hail the Queen!] I read this in Russian, while the rest of the group had @LizoksBooks’ marvelous translation. Abgaryan is a contemporary Russian-language Armenian writer, and the novel takes place in a fictionalized remote Armenian village in an unspecified historical moment. The few villagers who are left should be dying out, but as this charming and poignant novel shows, one is never too old or too isolated for life and hope. Everyone in the group loved it, and I gifted it to one of my closest friends for her birthday.

Seishi Yokomizo, The Honjin Murders (trans. Louise Heal Kawai)

My thanks to @kaggsy59 for the review of this title on her wonderful book blog, which is where I think I first heard about it. I was dying (I know) to read it, and then it arrived as a birthday gift from the same friend to whom I gifted the Abgaryan. A locked-room mystery, The Honjin Murders is the first in Yokomizo’s series with the brilliant detective Kosuke Kindaichi, who figures things out when it seems impossible to. The murders are gruesome, the story suspenseful, and the solution fantastically done. I don’t know Japanese literature and was very glad to enter this world at least a little bit. Really looking forward to reading the other books in this series that have been translated into English.

Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past (trans. C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin)

Fair warning: most of you will hate what you’re about to read; unfollow me if you have to. I started this before the pandemic and eventually found the #ProustTogether group spearheaded by @literatureSC. [Ed. – How nice!] This wonderful group was hands down the best thing about reading Proust (I’m easing everyone in slowly for what’s coming). [Ed. – Wait what?] What can be said about this book that hasn’t been said before? How about: I was bored to tears reading it? [Ed. — *sputters*] (Actually, that has been said before. By my dad, who years ago also slogged through every word. It must be genetic.) Of course, there were some strikingly beautiful images, several things the narrator said about human beings rang true, and this work’s importance in terms of literary development is undeniable. But the unbearably neurotic narrator kept saying things for thousands of pages with precious few paragraph breaks [Ed. – She seems to be saying this like it’s a bad thing??] in the amount of excruciating detail that had me screaming in my head that I don’t care what French high society wears, while wishing badly for a recognizable plot. [Ed. – But but…] The screaming was loudest with the Albertine volumes, where if I had to hear about his narcissistic obsession one more time … oh, wait. His sleep-assaulting her with his tongue didn’t help matters. [Ed. – Okay, that is genuinely awful.] Also the lack of editing, whereby characters kept dying and coming back to life in subsequent volumes. Proust’s own death before final edits is a cautionary tale for all who write. I could go on, but that would just be taking a page, or several hundred, out of Proust. During the group read, I managed to royally piss off one (several?) of the group members with my comments, as I’m sure I’m pissing off most people reading this now, but since everyone knows I have no qualms about verbalizing distaste for major male writers, so be it. [Ed. – I’m not angry, Yelena, just… need to have a quiet sit for a minute…]

Jaroslav Hašek, Pokhozhdeniia bravogo soldata Shveika (The Good Soldier Švejk; Russian translation by Petr Bogatyrev)

Another group Twitter read, also headed by @literatureSC; reading this alongside Proust provided the best antidote! Czech was my second Slavic literature in grad school [Ed. – Let’s all just pause and savour how awesome that is], and I’m so grateful for the several Twitter group reads that led me back to this rich body of work. The most popular Czech novel and one of my dad’s favorite books, Švejk is a hilarious and poignant indictment of the brutality of war that never resolves the question whether the screwball protagonist is a simpleton or someone much more profound. The novel is illustrated by Josef Lada, and the Russian-language edition, which came with us from the Soviet Union, has his color illustrations; I had to post them in a Twitter thread because they are so wonderful. I’d started this book twice before, in both Russian and English, so I’m happy to be able to say it is finally finished, even if the book itself remains unfinished due to its author’s death, which in this case, makes it no less fantastic for that. [Ed. – Oh now it’s ok for an author to die…]

Bohumil Hrabal, I Served the King of England (trans. Paul Wilson); Too Loud a Solitude (trans. Michael Henry Heim); Closely Watched Trains (trans. Edith Pargeter)

These were all rereads, the first two with a Twitter group led by @ReemK10, the third because I had it on my bookshelf along with the other two and went for the trifecta. All feature ordinary protagonists doing not so ordinary things, in Hrabal’s blend of absurd humor and deeply human emotions. Too Loud a Solitude, a love letter to books that uses imagery from the Holocaust, is one of my favorite novels, translated by my very much missed graduate advisor, who I think would be thrilled about all the Czech group reads and BookTwitter in general.

Zdena Salivarová, Ashes, Ashes, All Fall Down (trans. Jan Drábek)

Another reread, this one on my shelf next to the Hrabals. I think I picked it both because it was written by a woman and because I needed something as physically compact as this edition to bring on my only and very short trip during the pandemic to beautiful central California. Ashes, Ashes is the doomed love story of the Czech female protagonist and a Latvian basketball player whose team comes to play in communist Czechoslovakia. A straightforward, quick read that shows how the communist system devastated people’s personal lives. Salivarová immigrated to Canada after Prague Spring, where she and her husband, writer Josef Škvorecký, founded 68 Publishers, which was instrumental in publishing Czech writers banned in their own country.

Frances Burney, Evelina

Another Twitter group read, led by @Christina5004, and a reread of a novel that threw me back to my fantastic eighteenth-century British women writers class in college. Even though Burney squarely divides characters into good and bad with no shades of gray, this epistolary novel about Evelina coming of age and learning how to be in the world is engrossing and often hilarious. Reading the notes my twenty-one-year-old self left in the margins in a bright purple pen made me nostalgic: no one will be surprised to hear that feminism has been a constant throughout my life.

J.L. Carr, A Month in the Country

I’d never heard of this novel (I know, I know) until several people talked about it on Twitter. I was especially intrigued because it has the same title as Turgenev’s play, but it actually reminded me of Chekhov’s “House with a Mezzanine.” I loved the setting of post-WWI England and the wistfulness of the writing, but most of all, I loved that I was reading a novel outside of my usual material. BookTwitter was right about how good it was. BookTwitter is fabulous. [Ed. – Amen!]

The rest of the titles come from the syllabus of my class on contemporary Russian women writers and writing the body; I read them in Russian alongside the students, who read the translations below. The class is based on my dissertation, which discusses the explosion of women’s writing in the late Soviet/early post-Soviet periods, writing that went radically against the patriarchy and puritanism of Soviet and Russian literature. For the first time, women writers were producing works in which female bodies burdened and engendered by sexuality, violence, disease, abortion, miscarriage, etc. were at the center of the texts. I can talk everyone’s ear off about this topic, so I’ll stop, but if anyone is interested, I’d be happy to send the syllabus and/or the pdfs of some of the harder to find titles. We also read essays by the feminist theorists associated with the theory of writing the body: Hélène Cixous’s “The Laugh of the Medusa” (trans. Keith Cohen and Paula Cohen), selections from Luce Irigaray’s This Sex Which Is Not One (trans. Catherine Porter with Carolyn Burke), and an excerpt from Trinh T. Minh-ha’s Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism; those are readily available.

Liudmila Petrushevskaia, The Time: Night and “Our Circle” (both trans. Sally Laird)

During Soviet times, Petrushevskaia could get very little published, not because of politics but because her texts revel in exposing the dark, awful side of human beings, which went squarely against Soviet ideology. When she started getting published after the Soviet Union’s collapse, many readers and critics were dismayed by her frankness. Things have fortunately changed, and she is now one of Russia’s most famous and critically acclaimed writers. The Time: Night is her Russian Booker-nominated masterpiece of familial dysfunction, and “Our Circle” is one of her most well-known short stories showcasing the same, but this time with alcohol. [Ed. – I refuse to believe there is no alcohol in the novel. I mean, it’s Russian, right?] One of the many things I appreciate about her is that her work goes radically against the idea, propagated by both Soviet and post-Soviet culture and literature, that women are naturally maternal. Rather, maternal bodies are prime perpetrators of abuse. In general, bodies suffer all manner of abuse and violence in Petrushevskaia. In her hands, it makes for phenomenal literature.

It wasn’t on my syllabus, but I also read Petrushevskaia’s The New Adventures of Helen (trans. Jane Bugaeva) and the collection from which this new translation comes, Nastoiashchie skazki (Real Fairy Tales), but as this was for a forthcoming review, I’ll save the discussion for then.

Marina Palei, “The Losers’ Division” (trans. Jehanne Gheith)

From St. Petersburg, Palei now lives in the Netherlands and writes in Russian. “The Losers’ Division,” an early work, is part of a four-story cycle that has a hospital setting; like Chekhov, Palei is a writer with a medical degree. This story is set in an obgyn ward handling both pregnancy and abortion in a Soviet backwater town, which should give an idea about what happens to women’s bodies in this story.

Yelena Tarasova, “She Who Bears No Ill” (trans. Masha Gessen)

At the center of Tarasova’s text is a woman whose body and mind are being ravaged by a debilitating illness. The story approaches the body/mind divide in a non-traditional way, while breaking stereotypes surrounding femininity and female attractiveness. Gruesome and powerful.

Svetlana Vasilenko, Shamara (trans. Daria A. Kirjanov and Benjamin Sutcliffe) and “Going after Goat-Antelopes” (trans. Elisabeth Jezierski)

I got to interview Vasilenko when I was doing dissertation research in Moscow; in addition to her own writing, she also spearheaded the publication of two all-women anthologies in the early 1990s when male editors wouldn’t publish these writers, thus helping to institutionalize contemporary Russian women’s literature. Shamara is the story of a woman living under unrelentingly brutal conditions with her rapist/husband who finds a way to endure, while “Going after Goat-Antelopes” starts out as a story of a married woman’s attempted tryst and then plays a complicated game with the reader about what’s actually going on. Sexuality and violence are very present in Vasilenko’s work, but hers is a unique approach in that female bodies also sometimes navigate both the physical and non-material realms.

Iuliia Voznesenskaia, excerpts from The Women’s Decameron (trans. W.B. Linton)

I’ve written both an academic article and a Punctured Lines blog post on this novel I love beyond words, so anything I say here would be repeating myself, but at the risk of repeating myself: this novel in which ten women find themselves quarantined (ahem) for ten days in a Leningrad maternity ward and tell each other stories to pass the time looks unflinchingly at violence against women and celebrates female sexuality and female friendship. It is heart-wrenching, hysterical, raunchy, and consistently beloved by students in this class. A feminist riff on Boccaccio, The Women’s Decameron is writing the body in all its glory, Soviet-style. Read it, read it, read it.

Liudmila Ulitskaia, “Gulia” (trans. Helena Goscilo)

Like Petrushevskaia, Ulitskaia is one of Russia’s most famous writers, who’s incredibly prolific; this very short story is a small but wonderful part of her oeuvre. The protagonist, Gulia, is a woman of advanced age with a body that shows it, which in no way prevents her from seducing and having a one-night stand with her best friend’s much younger son. Unique for its celebration of older women’s sexuality, this story is a delightful illustration that age is no barrier and women definitely want it.

Valeria Narbikova, In the Here and There (trans. Masha Gessen)

In the Here and There is the first part of a short three-part novel, but stands on its own. Narbikova was the other writer I interviewed during my dissertation research trip, and it was such a pleasure to meet this unique, in-her-own-world individual, even if I had my wallet stolen in the Moscow metro on the way to her apartment. When Narbikova came onto the literary scene in the late Soviet period, some called her a writer of erotica (she isn’t), and all took notice, often with dismay, of her highly experimental, stream-of-consciousness style. There’s definitely a lot of open depictions of female sexuality in her work, including In the Here and There, which has a (brief) orgasm scene, but Narbikova’s real flirtation is with the Russian language, which she twists and shapes into her own medium that’s happy to disregard the rules of orthography and punctuation. Her works often eschew chronology, traditional structure, etc. in an effort to find new ways of saying things and therefore of living, and loving, differently. I’m not usually a fan of experimental writing, but I really love her.

Jeanette Winterson, Written on the Body

There are other choices for the “token Westerner on the syllabus to show that writing the body is something women writers from many literary traditions do,” but how could I notinclude this title? The novel, which recounts the narrator’s frantic search for their cancer-stricken lover who has gone away, does not specify the narrator’s gender, thereby challenging readers’ assumptions and making them confront their own stereotypes. It’s exuberantly written, with a sharp sense of humor. A good way to end the class and this list.