Why yes we are hurtling to the middle of 2024, but I’m popping in with one last take on 2023. And I’m thrilled that it’s by a writer whose intellect and fearlessness I admire a lot. Shinjini Dey is a writer of criticism and essays. She has written for the Cleveland Review of Books, Los Angeles Review of Books, Contemporaries of Post 45 and others. She can be found @shinjini_dey.

I’ve always had projects and reading lists—organized by author, by zeitgeist, by theme—but I couldn’t stick with it in 2023. I wish it had been a dilettante-ish year, with a range as wide as its corners, but instead I kept falling out of love. My reading has been distracted, unintentional, mawkish in its inattentive flailing. There have been writing blocks followed by reading blocks and its strained reversal. Late in January, Dorian asked me to write something, anything, for this blog. And I wondered whether retroaction could salvage a shape from the romance. [Ed. – Yes, I’ve wanted to feature you here for a while! And let me say to everyone, Shinjini turned this piece in almost three months ago. It’s me, the problem is me.]

Despite this, I was surprised. I read about a hundred books during the year (a hundred-and-six to be precise). Some of these I read for review/essays, and some to discover myself anew, and others just to anchor me. All rather bland held against the high drama of my assumptions. Does a life spent reading always feel incongruous to the readings? [Ed. – Yes.] In April I read Mick Herron’s Slow Horses, all six of them, because I wanted to feel invisible, hidden in the shadow of large institutions. This British spy series encapsulates a closed world—one where the spies create the conditions for their own stature and relevance by fucking up, creating problems for the next cog in the wheel. It’s high workplace drama about bosses never cleaning their own spilt guts, ideologues, and semen; something pedantic about their missions and something bumbling about their failures. What better way to feel comforted about your own rootlessness by digging through Empire’s anxieties and paranoias? [Ed. — best description of these books ever.]

The other series (and every series when read in one long sighing week produces the effect of binging, and binging always feels slightly abject) [Ed. – Did Lauren Berlant write about binging? Because binging feels like a real cruel optimism situation…] harkened back to a time when SFF was intricately reimagining science through science’s own conceits. I dwelt in a time when scientific progress did not mean approaching singularity through hyperrealism. I read Nancy Kress’ Sleepless series about the utopic possibility of eugenics and post-scarcity: a tragic, generational epic. Connie Willis’s Doomsday trilogy and quite a few of Kage Baker’s Company books, where time travel is the occupational labour of history/historiography departments. Both series possessed this affective irony towards the workplace and bureaucracy—and one may call this class consciousness, but I read it as a national culture emerging out of unions and well-paying blue-collar jobs. But, because of it, the genre negotiates with political economy, and speculative utopianism was always its plumed stage. Was Jameson right? More likely accurate about then than now. [Ed. – That seems right. Surprising to me how important he seems now; in my day he was treated as a bit of a one-hit Vegas hotel wonder.]

In a nostalgic mode, I also read the Avidly series of short monographs (Avidly reads Poetry, Avidly reads Theory, Avidly reads Screen Time, etc.) imagining either being a young student in the academy, or someone handing over introductory texts to young students. I gave to myself the gift of (potential) responsibility. So much of literature is tempered by the academic institution, so much personhood is granted through the production of a self within that institution (does dark academia then seem simulated, sublimated?). I, too, keep oscillating between the academy and the paraphernalia of that world—wary of getting too close, bothered when its it gets too far out. I keep the academy at arms’ length [Ed. – smart], and these simple, fast-paced books, which offer the vicarious experience of a passionate hunger for knowledge, have become part of my tumultuous pattern. I read a few every year. I also read Glitch Feminisms by Legacy Russell, which was blurbed by Lil Micquela (the fictional influencer), and though it is a manifesto, I disliked how repetitive it was, how much it relied on new idioms.

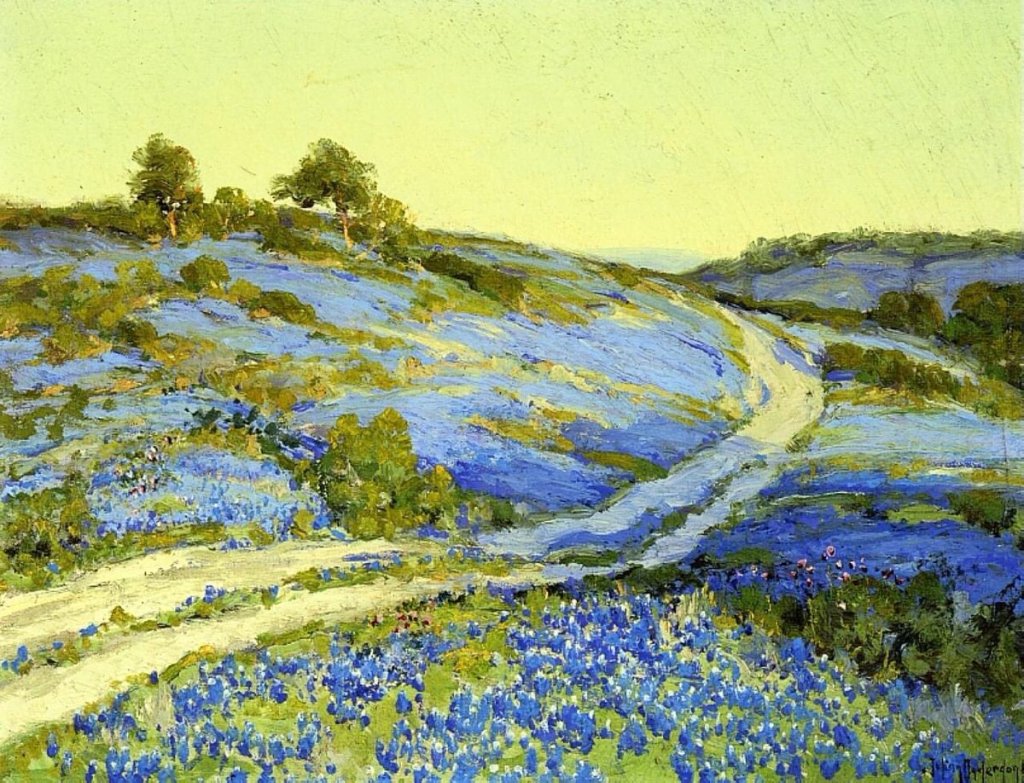

Nonetheless, there was specificity. There were campus novels too (Brandon Taylor’s Real Life, Elaine Hseih Chou’s Disorientation) and those that aren’t campus novels but skirt around that polyphonic experience of camaraderie and community, which couple the grind with the sexual, romantic, intellectual or even self-mythologizing pursuit, whose narrative world is small, even incestuous. [Ed. – Great description!] I sought out The Savage Detectives by Roberto Bolano (trans. Natascha Wimmer) to read again after being bowled over by Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers, a novel that was truly political, that captured so much about the relationship between art and politics. Kushner posed (and answered differently) the question that animated Savage Detectives as well, the question about an attractive young woman who circulates within an artistic economy as either symbol or commodity, and why there is no political economy without sexual politics. The difference between Real Life or Disorientation and these novels is not that Taylor and Chou’s work is devoid of sex—there’s enough sex, beautiful sex—and not that the community forms without the sexual charge—it’s there, homosocially, homosexually—but for Kushner or Bolano, the art doesn’t exist without sexual politics. And so, I turned to Lauren Berlant (I often turn to Berlant). And I read novels that mimicked this charged atmosphere: I read all of Nona Fernandez’s memoiristic narratives (Space Invaders and Voyager, both translated by Natascha Wimmer) set during the Chilean dictatorship that took me into communities congealed through terror (and what happens when terror becomes mundane, leaving fantasy to paper over the sinister boredom that persists). [Ed. – You sold me on these!] I also became impatient alongside Natascha Wimmer, devouring what she translated, placing her at the center of my explorations into literature. I read other Bolanos. I swam through Kushner’s other novels and decided, no, The Flamethrowers reigns supreme.

I read two other novels with an academy at the center of a character’s moral crisis: Anjum Hassan’s History’s Angel and Dorothy Tse’s Owlish. Hassan’s book is about pedagogy in crisis because of right-wing nationalist politics. It picks up with a middle-aged teacher of history having to reconcile himself to being made historical and read against the grain, to being revised as a Muslim man in contemporary India. How does one negotiate everyday life within fascism, when ebb and tide all conspire to erase you? Hassan’s protagonist turns outward as a witness, following its Benjaminian namesake—but in Owlish, the professor, at odds with an island under occupation, turns to fantasy, to dolls, to magic; he relieves himself of the burden of public life. Read together, these novels depict intellectual thought in the public sphere as a lost creature, howling, crying, playing pretend. [Ed. – Such an enticing comparison of two books I am now keen to read!]

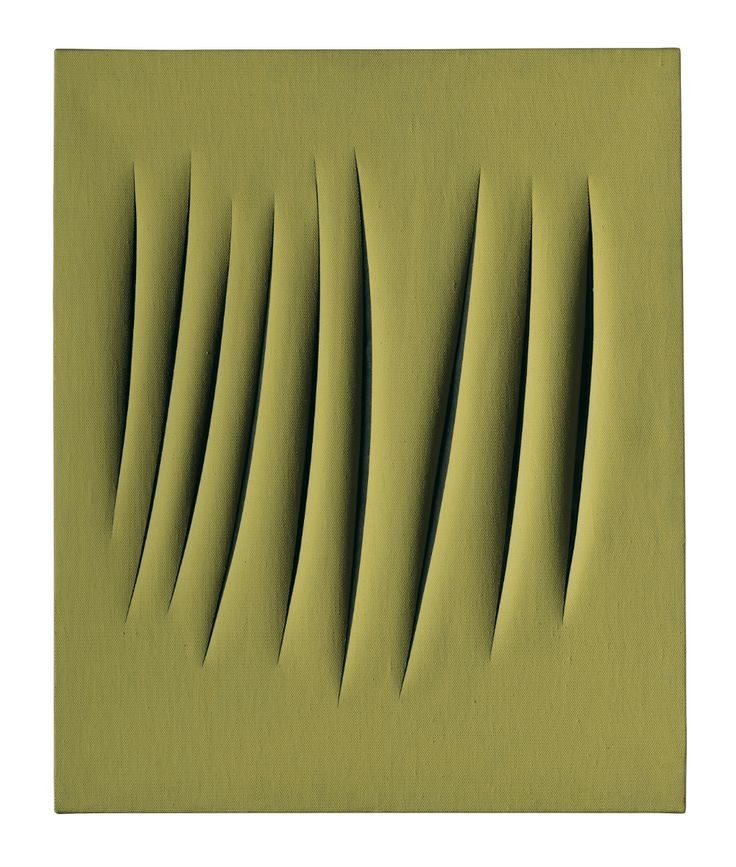

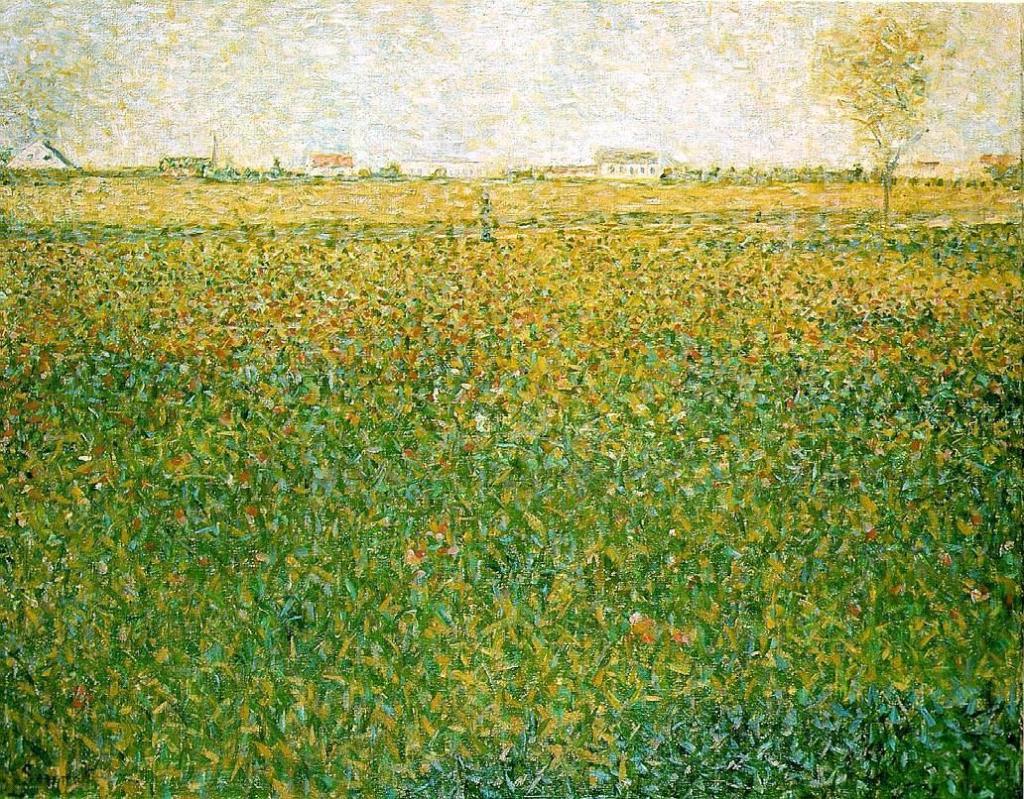

I read Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These because of its deceptively short length but the novella made me delight in quiet and steadfast prose, prose that keeps up with its characters, that makes room and board for them; I read Foster to prolong with Keegan’s tight sentences. I developed a taste for surfaces, writings that reflects off water or other surfaces, rippling through each page—and the way I am sometimes, impulsive yet able to sustain that impulsiveness, I turned to read narrative theory (Surface Relations by Vivian L. Huang, then Narrative Discourse by Gerard Genette, as one does). The more I thought about flatness, as an important part of the surfaces, the more I wondered about disaffectation as a minor affect. I taught a few students about flatness in Sofia Samatar’s Monster Portraits as an exercise in narrativizing personhood. But by then I had already hit financial crisis and it sought to narrate all other crises through debt and management and I could do nothing. I read poetry: Sharon Old’s Odes, Franny Choi’s Soft Science and The World Keeps Ending and the World Goes On, Tishani Doshi’s A God at the Door, Amelia Rosseli’s Hospital Series, Diane Ward’s TROP-I-DOM, Jenny Zhang’s My Baby First Birthday, Yi Lei’s My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree, Solmaz Sharif’s Customs and more Sean Bonney. [Ed.—Well, I know Olds, anyway. This litany of names unknown to me makes me feel… old.] In abstraction and particularity, I got through a bad week and then I read, voraciously, novels about workplaces, one in between each new gig I applied for.

There are a few glib things I can say about workplace narratives (I can also say a few thought-out things), but I’ll limit myself to the glib and pithy since the rest is work.

- There were once too many workplace narratives set in a publishing house/bookstore—but the content farm is the new publishing house (Emma Healey’s The Best Woman Job Book or Hana Bervoets’ We Had to Remove This Post). Corollary, the workplace novel that is set inside the content farm and the tech industry is about a cog in a wheel, but the cog is unable to narrate the wheel. Its precarity is homelessness (Sarah Rose Etter’s Ripe, Satoshi Yagisawa’s Days at the Morisaki Bookshop, Sarah Thankam Matthews’ All This Could Be Different)and its dystopic imagination is noir homelessness (Jinwoo Chong’s Flux, Victor Manibo’s The Sleepless, Molly McGhee’s Jonathan Abernathy You Are Kind). There are few workplace novels about unobviated homelessness.

- The best workplace narratives are about artists (Emily Hall’s The Longcut, Tade Thompson’s Jackdaw) and the outstanding ones are about sex work and reproductive labour (Eliza Clark’s Boy Parts, Olga Ravn’s My Work translated by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell, Melissa Febos’s Whip Smart, Gillian Rose’s Love’s Work, Polly Barton’s Porn: An Oral History). It is impossible to be an artist without being a whore or a mother, which is to say, only a whore or a mother understands the conditions of the economy where you have to labour past the point of love (Eva Balthasar’s Boulder). [Ed. – I want to read the longer version of this little essay you’ve just given us!]

Alongside these books I read some Eva Ilouz (Cold Intimacies, What is Sexual Capital written with Dana Kaplan); I also read histories of candy—but none of those texts are worth mentioning here. But after the saccharine, it makes sense that I turned to novels where love was an abjection, an ejection from the real, the narrative of erotomaniacs—Evelio Rosario’s Strangers to the Moon translated by Victor Meadowcroft and Anne Mclean, Charlie Markbreiter’s Gossip Girl Fanfic Novella, Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes, Sheena Patel’s I’m a Fan, Anna DeNiro’s OkPsyche, and Lena Andersson’s Wilful Disregard.

Does my movement make sense? This movement from precarity to practice? There’s certainly something searching about it, an example not of how we write about crisis but about what we read through crisis. Self-identification and self-abnegation in equal measure, with a little treat. If after, or in between these, I read some horror, something murderous, somethings with a mystery to suspend this accounting, would it be unforgivable? [Ed. – It would not.]

So there was a litany of murders.

- A mystery, Raza Mir’s Murder at the Mushaira, which plays that trick of the narrator withholding information of the murder till it end; the trick makes me experience the detective as fascist. Imagine making Ghalib fascist!

- Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Paramo, translated by Margaret Sayers, which carries kinship like a haunting. Perhaps here the diversion took me to read all of Yuri Herrera (Signs at the End of the World, Transmigration of Bodies, Kingdom Cons, Silent Fury), all the bodies that moved or need to be moved, and the corporeality of language in the fold. Babak Lakghomi’s South proceeded from Pedro Paramo into the wind and the desert.

- Tom Lee’s The Alarming Palsy of James Orr waited to be killed because he needed care in a staid, boring, unnecessary stasis.

- Michael Cisco’s The Divinity Student killed language and taxidermied the remainder. So did Hwang Yeo Jung’s The Spectres of Algeria, translated by Yewon Jung, and then made a community of writers rewrite it from memory.

- Sigrid Nunez’s The Last of Her Kind has a murder that is about the conviction of law and conviction of spirit—where the scandal of murder is always less than the scandal of biographical detail. [Ed. – My fave Nunez: nobody ever mentions it.] Norman Patridge’s Dark Harvest is also murder by institution, a novel that is aware of how much the ritualized depends on cinema. Eugene Lim’s oeuvre, which has a suicide at its heart, is aware of this scandal too.

So, in the litany of murder there was language, form, genre, a litany of gestures of remembering and remaindering.

Is there a shape to these readings? There certainly appears an attempt to escape the form of the institution. At the end, plus or minus a dozen other books, it appears that there is still a romance of maladjustment, scabbing, survival, and complaint. [Ed. – Without the romance, scabbing is hard.]

In any case, these are the best and most indulgent shapes I can make. If I were to practice restraint, I’d say “the reader tried to change” and this would become an essay of self-fashioning—this is more, merely, a year in review. [Ed. – Thanks, Shinjini. One of the headiest of these reviews yet to appear here. Here’s to more institution-busting in 2024…]