A few months, when I was too busy to do anything about it, WordPress told me I’ve been writing this blog for ten years.

I’ve not always been the most diligent blogger, sometimes falling silent for months at a time, but I’ve always returned to it, and that’s not nothing. In fact, since I started keeping monthly logs in January 2019 (halfway through the blog’s life, which bewilders me, since surely that was just a couple of years ago) I’ve written a little something about almost every book I’ve read.

(In case you are new, or forgot, or never bothered to think about it before now: a few words on why I gave this place its unlikely—and from a branding point of view utterly self-defeating—name.)

It is quite likely that some things will change in my life next year. Fear not, though, I’ve no plans to shutter the blog. I’ll probably be happy for the continuity. But I do wonder if there are other kinds of writing I might do here. Like many writers, I write best when I’m working on more than one project. I’m using part of my summer to craft a proposal for a book on teaching Holocaust literature at this moment in US history: I recently finished a course from the wonderful Anne Trubek of Belt Publishing that has given me a good start. (Agents and publishers, all my forms of communication are open lol.)

[My daughter says using lol is cringe. Sorry. But how else am I supposed to indicate “I know that is preposterous and I am kidding except that I would really love for it to happen”? Hahahahaha or something?]

I’ve been wondering how I might bring some of that writing variety to this space. When I first started EMJ, I wrote about one book at a time. No surprise to anyone who reads me, these posts were long. Often really long. They really helped me figure out what I thought of a book, though I’m not sure people wanted to read them as much as they did my still-long but shorter responses to a month’s worth of reading. I’m still fond of those early pieces, especially the first one, on a book I still think about a lot, Caleb Crain’s Necessary Errors. Here are a few more that hardly anyone read, but might be worth dusting off. On Irmgard Keun’s After Midnight. On Philip Marsden’s The Bronski House. And, way long, on A Little Life. There’s a ton more in the archives.

I have to admit, though, that the rhythm of the last five years has worked well. The monthly reviews offer a balance between breadth and depth, but would you prefer more pieces about just one book? And what about non-book topics? I’ve always shared writing created for other occasions (like becoming Jewish or reflecting to new students on old friendships). For a while I wrote regularly about my teaching, which I loved doing: I’m basing the book project on some of that stuff. Honestly, I don’t know how I wrote all that stuff, though. My daughter was young then and needed a lot more from me and my wife. Where did the time come from? I guess I was younger too. And that was all pre-covid. I think people overstate the changes between then and now (rather: they overstate the wrong things and ignore the main thing: we still live in a pandemic, we still don’t value the most important kinds of work, our way of life is killing us and the world). But I feel my working life has changed a lot. I don’t think I’m just being middle-aged when I say that it’s harder to be in a helping profession than it used to be. Anyway, I don’t know that I’ll have enough to say about teaching for me to write about it here and in the book. But who knows? Maybe writing about other kinds of art might be fun. The obvious example is film, which used to be a huge part of my life but fell away in the press of family life and career pressures. I’m returning to movies, though: slowly but ever more surely. I might write more about what I’ve been watching. (I think this is the only film-related post at the blog?) Another idea is to invite others to contribute. I’ve had many guests over the years, whether through readalongs (remember those?), shared reading projects, or year in review lists. I love hosting other views, voices, and perspectives. Maybe I could do more in that vein.

What else? Obviously, the look needs refreshing. And yet I am so lazy about that kind of thing. Is it actively off-putting? I admire M. A. Orthofer for many reasons, one being his indifference to graphic design. His site looks the way it looks, the content is what matters, and now it’s so iconic I for one would be crushed if he changed things. This place is no Literary Saloon, but maybe I am inching toward “so old-fashioned it’s actually cool” status. Thoughts?

As you can see, this post is a mixture of questions and ideas: what I wonder about and what I might do. But really what I’m writing here is both a plea for feedback and an expression of gratitude. What do you want to see here? More of the same? Something new? Like what? Whatever your answer, I want to thank you for reading. Blogs are so out of date; social media had made other kinds of communities, other forms of interaction; so many platforms share the thinking of so many smart readers and writers. That you’ve taken an interest in what I think means so much to me. As I’ve written before, I don’t know many passionate readers in real life; this community of readers around the world has meant the world to me. Thank you for everything you’ve taught me, the reading suggestions you’ve made, and the support you’ve offered. I’m filled with gratitude.

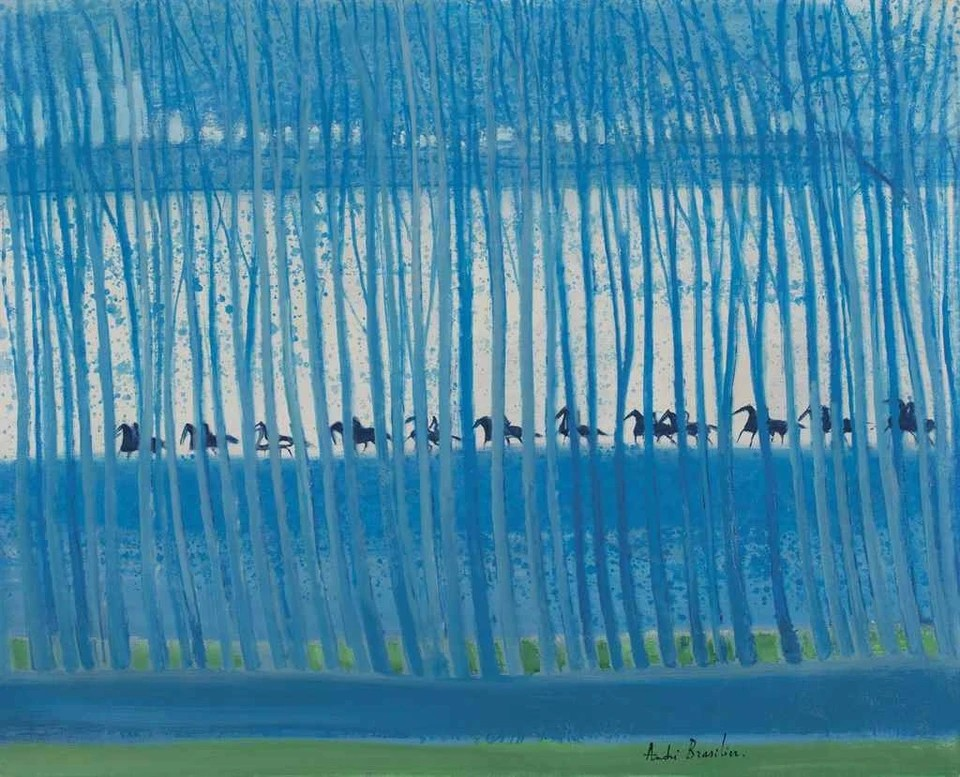

Onwards! Still many book mountains to climb.